Is the market in European Coco bonds about to pop?

They were conceived as a clever way to stop taxpayers being put on the hook for bank failures. But ‘contingent convertible’ bonds are turning out to be far from simple in practice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In May last year Martin Taylor, the former chief executive of Barclays Bank, addressed a crowd of high-powered financiers in the ballroom of the InterContinental Park Lane hotel in London.

Mr Taylor, an adviser to the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee and an influential voice on market risk, spoke darkly about his fears for Coco bonds, a quirky-sounding debt instrument launched in the wake of the financial crisis.

“I talk to a group like this about credit matters with the greatest timidity. I am sure you are good citizens and desire to exercise exemplary scrutiny. But I wonder whether you will flip – like the holders of European sovereign bonds before 2010 – from believing all issuers equally safe to thinking many equally precarious when the sky next darkens,” he said.

Skies have not only darkened this week, but Mr Taylor’s words have a prophetic rings: investors have indeed flipped out with concern about Cocos after the German lender Deutsche Bank was forced to reassure investors it could meet interest, or coupon, payments on its Coco bonds.

The move has stoked fears that something is rotten at the heart of the European banking sector and led many to question why Cocos – considered a silver bullet solution – have melted like their chocolate breakfast cereal namesake in the face of market turmoil.

Cocos, formally known as contingent convertible bonds, were born out of the 2008 financial crisis as a solution for stricken banks without the need for a state bail-out.

They work quite simply on the surface: banks issue them to finance their business like normal bonds but they morph into equity if a bank’s capital falls below a certain threshold. This automatically reduces a bank’s debt and boosts its capital buffers at a time when external investors could be reluctant to inject new money.

The flexibility removes some of the risk inherent in loading up bank balance sheets with debt. But herein lies the rub: how can a bank be flexible on debt obligations without spooking the market into thinking it is in trouble?

A recent move by the European Central Bank to publish an obscure test of bank risk, known as the Srep ratio, has driven the recent upset in the market. The results have stoked fears in the minds of credit analysts about whether recent market shocks – ranging from low oil prices to the slowdown in China – could inadvertently cause banks to breach rules which would prompt regulators to stop them paying Coco coupons.

Many lenders – such as Spain’s Banco Popular Espanol, Italy’s UniCredit, BNP Paribas of France and Deutsche Bank – are now getting perilously close to falling into the zone, according to Hermes, posing questions about how far banks will go to protect their Coco coupon payments.

“All these banks still have some strings they can pull,” Hermes’ credit strategist Filippo Alloatti said. “The fundamentals are still the same; this is a test for the Coco market and the incentives for the banks to pay these coupons, if they can, are still there.”

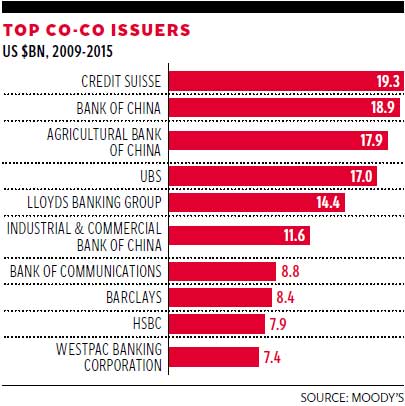

Cocos have grown rapidly since launching in 2009, attracting credit investors keen for high-yielding bonds in a world of low base rates.

Last year was a high-water mark, with banks issuing $175bn worth of Cocos – dwarfing $50bn in 2013 and $14bn in 2009, according to Moody’s.

Yet fears over the Greek debt crisis and the slump in China put a chink in the armour. Issuance slowed to around $77bn last year and this year looks worse, with predictions of $35bn worth of bonds now looking highly optimistic in light of recent events.

Just two Coco issues have come to market this year, according to the data provider CreditSights – from Crédit Agricole and Intesa Sanpaolo.

Many say the Coco market is now effectively closed for the rest of the year unless policymakers simplify the rules and kick-start issues back into life.

“The regulator has made a mistake in the way they are designed,” credit manager Lloyd Harris from Old Mutual Global Investors said. “The regulations are far too draconian in Europe and will have to change. It is potentially difficult for the market to come back to the extent it needs to unless some changes are made.”

One solution could be adopting a US version of Cocos, which are considered less complex than their EU counterparts. If a bank reaches the point of going bust in the US, the Coco is simply bailed in and losses are borne by the bondholder.

In contrast, EU regulators have over-egged the cake by adding additional layers of complexity about how and when banks can pay bondholders. “We should not forget these have been designed by regulators for regulators,” said Gildas Surry, an analyst and partner at credit investor Axiom Alternative Investments. “At some stage, the ECB and the Bank of England will have to defend the format.”

He added that it would difficult for Europe to adopt a US model because it is now “less mature” than the European model.

“The level of regulation and supervision in Europe is now extreme,” he said.

Martin Taylor has been both a banker and a market quasi-regulator. Perhaps it’s time the authorities starting listening more to the former and less to the latter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments