Iceland: dancing on the brink of bankruptcy

For years, Iceland had enjoyed an economic climate more favourable than its weather. But the country was leaving itself bitterly exposed, reports Michael Savage in Reykjavik

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The days grow ever darker in Reykjavik. Gone is the almost eternal daylight, which washes across Iceland's capital in the height of summer. A darkening gloom arrives earlier each day now. An icy wind blows in from the east. Darkness will be a constant presence here soon as winter sets in.

If ever a nation's changing climate reflected the mood of its people, it is here. Every morning, it seems, the residents awake to news of fresh problems in their country's banking system. Last week, the country's third largest bank was nationalised. This week, the government dismissed the board of directors of Landsbanki, its second-largest bank, and put it into receivership. On Monday, the Prime Minister, Geir Haarde, warned its citizens the country faces bankruptcy.

Iceland, with a population the size of Bristol, is rated by the UN as the most developed society on earth. But it now faces less welcome distinction as the country worst exposed to the credit crunch, with banking debts several times bigger than its economy.

Laugavegur, the capital's chic main stretch, is eerily quiet. At one of the main branches of Landsbanki, executives could be seen yesterday pacing the upper floors, mobile phones held to their ears, hands on foreheads. Galleries, antiques stores and jewellery boutiques, which sprang up in the boom days of the past decade, were empty. Some are closed altogether. It is not a day to be in business in Iceland.

The few Icelanders who are out and about gather in tight groups, shielding themselves from the wind and discuss the latest disasters to strike its banks. The credit crunch is the only topic in town. Many head to their banks, where a steady stream of concerned savers enter to inquire just how safe their money is. This bleak picture of shattered consumer confidence does not seem out of place in a nation famed for its Viking sagas. It now has a new epic tale to tell: how its banks have brought a whole nation to the brink of bankruptcy. But many do not blame the lenders.

"The banks just did what banks do," said Siggit Valgeirsson, as he left the head office of Landsbanki, which holds his savings and his company account. "It is those in power, and the central bank, who have not behaved how they should. Too many of the people in control there are not experts, but politicians interfering in the economy."

Political appointments in the banking sector and a hands-off approach by regulators created the conditions for a massive investment binge among Iceland's banks and companies, funded almost entirely by foreign borrowing. Working with Icelandic entrepreneurs they made acquisitions across Europe including buying up major British high street names such as Hamleys, House of Fraser and Karen Millen.

"They were acting more like a private equity fund than a country," said Lars Christensen, head of emerging markets research at Danske Bank, who has been predicting meltdown in Iceland since 2006. "They made themselves the most exposed country when the credit crunch finally arrived."So successful were they that the assets of the banks amounted to 10 times the country's GDP by the end of last year. But that made it vulnerable. When disaster struck, it was rapid. The country's third-largest bank, Glitnir, was nationalised last week. Its overstretched firms were ordered to hand back some of the many foreign companies they had bought up.

Yesterday morning, the government revealed it had taken control of Landsbanki after the bank was forced into receivership. The whole board was sacked on the spot. It was the government's first decisive move after passing a series of emergency laws on Monday night, giving it carte blanche to do whatever it would take to rescue its bloated banking sector. The Prime Minister even addressed the nation directly on Monday, assuring his 320,000 countrymen that their savings would be guaranteed by the state. Its biggest bank, Kaupthing, has been lent €500m by the central bank.

But it is not just the banking sector that is suffering. Huge borrowing has fuelled inflation, now running at 14 per cent. To make things worse, Iceland's once-strong currency, the krona, has plummeted in value. Some stores are refusing to restock imported items before they have cleared their last stocks, fearful of making losses.

"I was lucky that I bought a big order from London at the start of September, just before the currency fell so far," says Hildur Simonardomir, owner of Galleri Simon, an arts and crafts boutique. "It has been 'buy, buy, buy' in Iceland for too long. This was always going to happen."

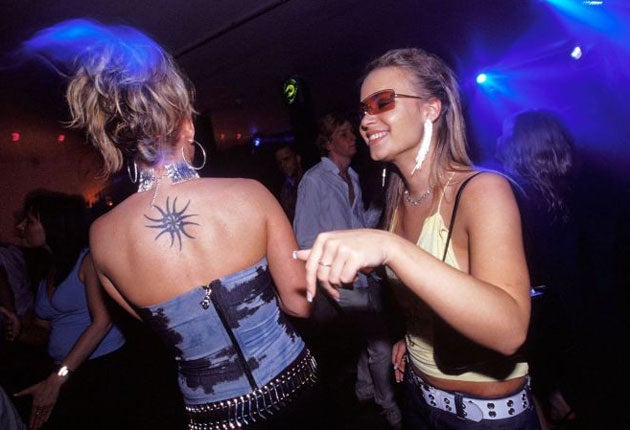

The collapse of the currency has created opportunities elsewhere. Holiday deals to Iceland, traditionally seen as too expensive for many travellers, are now more attractive. Bar owners in Reykjavik's central plaza, home to the main hotels, have begun to notice visitors drinking more alcohol – notoriously expensive before the krona plummeted. Bars that have become accustomed to hosting raucous foreign stag parties and Bacchanalian pub crawls are bracing themselves for even more visitors this winter. They look set to benefit from the extra spending money tourists have been handed with the fall of the krona. A beer cost up to £8 when the krona was at its peak, but can be bought for half that price now.

While shoppers seem to have fled the high streets, worried locals have not abandoned Reykjavik's hedonistic nightlife. Far from it. "Last week a lot of people realised how serious things were – I've never seen it so busy," said Insi Thor Einarsson, manager of the Café Paris, a daytime haunt that fills with revellers at night and stays open until 4am. "People have been coming downtown since then to drown their sorrows."

Eva Maria Porarinsdottir, a manager at Elding, a company offering whale-watching tours, says it may even stay open through the winter to take advantage of the interest. "We usually had to carry out all our business over six or seven of the warmer months as there wasn't enough interest to operate in the winter," she says. "It's hard to see the positives at the moment – I bank with Glitnir, lost a lot of money after recently buying an apartment, and this business has loans in foreign currency. But we need to make the most of the current conditions. I'm in the right industry to do that."

There may also be a resurgence of a trade that Iceland has traditionally been famed for – fish. "We are always considered a nation of fisherman, but with the boom of our financial sector and the huge money it generated were forgotten about a little bit," says Asbjorn Jonsson, the managing director of Fisk Kaup. "We are affected too of course – we hold loans with Icelandic banks and our loans are expensive. But the fishing industry will always be around, and the cheaper krona is helping us to export." Many Icelanders feel that the dramatic collapse of the financial sector was inevitable. But they are resigned to seeing through the hard times.

It is summed up by Gunnar Gunnarsson, a retiree, whose shares in the newly nationalised bank Glitnir have just plummeted. And he banks with Landsbanki, now in administration. "Things are hard but they will get better in the end. Don't worry – be happy," he says with a smile.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments