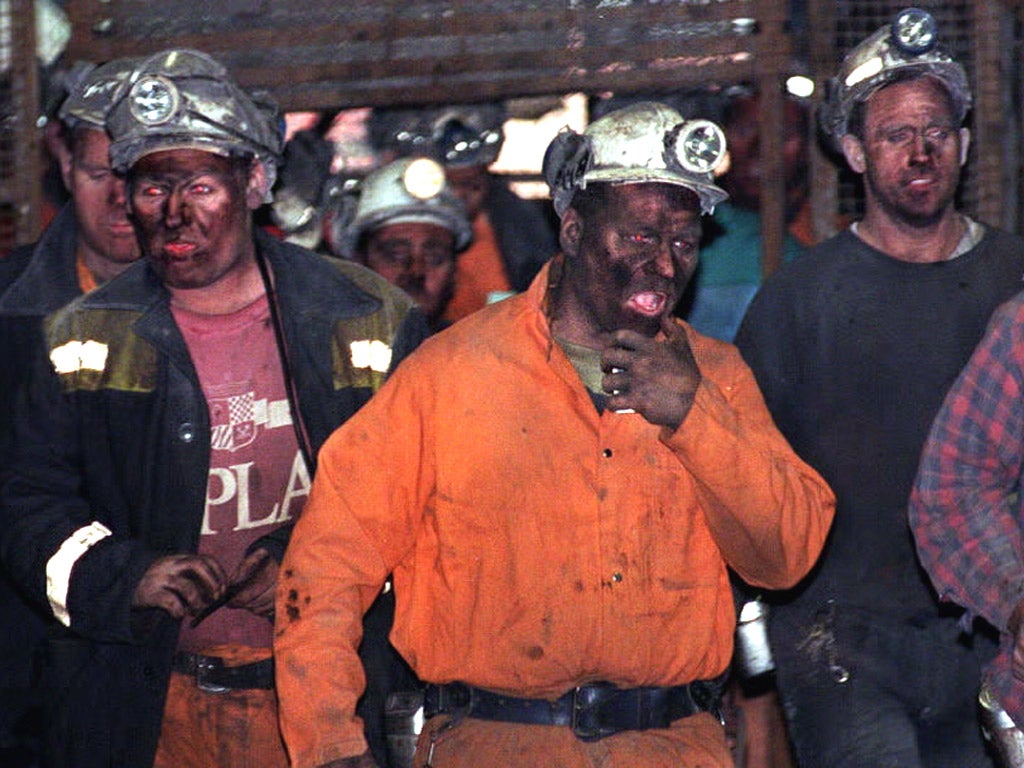

Another blow for Britain's coal mining

One of the country's last-remaining deep pits is to close, as the beleaguered industry shrinks still further

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain's beleagured coal mining industry suffered yet another hit yesterday as the owners of one of the country's last remaining deep pits announced plans to mothball the operation, with the loss of up to 540 jobs.

After 104 years of production, Maltby colliery near Rotherham in South Yorkshire, the scene of some of the biggest pickets in the 1980s strikes, is due to close after gas, water and oil leaks have effectively put coal face T125 out of business, on a whole range of grounds.

"The T125 panel is not viable on health and safety, geological, and financial grounds. Consequently, the board is proposing that T125 will not be mined and that the mine will be mothballed," said a spokesman for Hargreaves Services, the owner of Maltby Colliery, yesterday.

The announcement added to what was already a gloomy week for the mining industry, coming just two days after UK Coal took another decisive step toward the expected mothballing of its Saw Mill mine in Warwickshire.

At an emergency meeting on Monday, UK Coal's shareholders voted through a range of measures in an attempt to rescue the struggling group, which is the country's biggest coal miner. These include splitting off the Saw Mill mine into a separate legal entity, which means it can no longer be subsidised by the group's other mines or its profitable property arm.

Once the country's most productive pit, Saw Mill, which has been plagued by geological problems, will close by 2014 unless production rises and costs come down, putting 800 jobs at risk.

But the woes of Maltby and Saw Mill are only the latest in an industry that appears to have been in terminal decline since it produce 292 million tonnes of coal in 1913.

By the time it was nationalised in 1947, coal industry output had already declined to 200 million tonnes a year – from 1,038 mines – as the beginning of production of North Sea gas in the 1960s provided power producers with an alternative source of energy. By 1983, just before a further raft of pit closures prompted the miners' strikes, production was down to 120.8 million tonnes at 308 mines.

Last year, the industry, which was reprivatised in 1994, produced just 17.8 million tonnes of coal at 52 mines and employed just 6,419 people – a monumental decline from the 470,000 workers in the industry in 1947.

The decline looks set to continue, as the UK seeks to comply with EU legislation, introduced in 2001 and designed to reduce carbon emissions. This states that coal-fired stations built before 1987 – a particularly dirty source of energy – must either be modified with costly, modern emissions control equipment, or operate only for a total of 20,000 hours between 2008 and 2015, when they must come out of service completely. As a result, a series of coal-fired power plants will close early, significantly reducing customers for UK coal miners.

Furthermore, as power producers seek to reduce their carbon emission, they are moving away from fossil fuels to renewable energy in a development that will further hit demand for coal.

A fortnight ago, Europe's largest coal-fired power plant, Drax, announced a £700m plan to convert half its boilers in North Yorkshire to biomass materials such as wood pellets. This week, it emerged that Eggborough Power Station, which generates about 4 per cent of the country's electricity from its site in North Yorkshire, will convert from coal to biomass.

UK Coal, which bought the Maltby mine in 2007, said it would listen to proposals from staff and unions to table proposals on how to run the business viably and has promised to relocate as many employees as possible in the event of a closure.

However, analysts, the company and politicians, believe it to be unlikely that the mine can be saved, a move that is expected to result in the loss of most, if not all, of its jobs.

Although the likely closure of Maltby may be primarily to do with safety, it nonetheless chimes with the times. And it is unlikely to be anything like the last of the remaining mines to go.

Costly £330bn needed

A massive £330bn needs to be invested in Britain's energy infrastructure by 2030 if the power industry is to meet its target of an 80 per cent reduction in emissions based on 1990 levels by 2030, according to a stark new report from the London School of Economics. The figure, the first cost assessment to look as far as 2030, shows how long-term a challenge the transition to a low-carbon economy will be, said Volker Beckers, chief executive of npower, the energy provider that commissioned the research. Previous estimates had focused on the amount that needs to be invested by 2020, with regulator Ofgem putting the figure at £200bn.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments