Independent Appeal: The school giving beach beggars a ray of hope

For children in Bangladesh, the future's looking brighter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

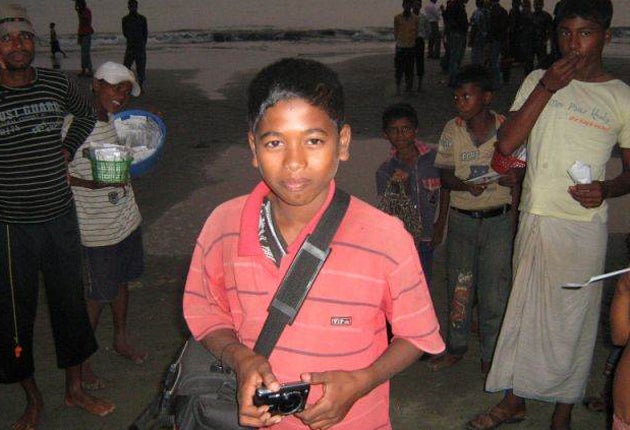

Your support makes all the difference.Every evening, as the sun starts to dip across the Bay of Bengal, 12-year-old Anawer Hossain makes his way to the beach, pulls out his camera and gets to work. If he's lucky, he can make the equivalent of £18 a month, snapping away and printing off the images at a nearby shop. But before he gets busy with his precious Sony digital camera, Anawer attends a drop-in centre where he studies and plays with other children. His favourite subject, he says, is Bengali.

On the Cox's Bazar beach there are as many ways for a child to earn a few hundred taka as there are tourists splashing in the water, eating peanuts, drinking coffee or lying in the sun. Some sell jewellery, others sing songs. Some simply beg. But what all these children have in common is parents reluctant to let them stop earning what they consider a vital income.

"We are motivated to educate these children," said Barun Dey, a programme officer at one of two drop-in centres in Cox's Bazar operated by a local charity, Mukti Cox's Bazar, set up specifically to help the children who work the beach. "There is a government school but it is not where these children live. Also, it's much easier for these children to come here. We are far more flexible."

The beach at this booming resort town in southern Bangladesh is a thing of wonder. Stretching more than 100 miles south to the border with Burma, locals claim it is one of the longest beaches in the world. But for hundreds of children, it is a place of hardship and struggle. It is where they go every day to earn a living.

Mohammed Sohel has been attending one of the drop-in centres for the past two years. The nine-year-old first started working on the beach when he was just three or four, as a beggar. At the spartan but brightly decorated centre, he studies English and Bengali, plays games with other children and takes part in music sessions. Now, when he leaves the centre and heads for the beach, he is no longer a beggar but a performer; rather than earning just 10 taka (9p), he can earn up to 10 times as much performing a song in Bengali or Hindi for holidaymakers. "In the mornings I come to school and in the evenings I go to the beach," says Mohammed, reflecting a situation that some in the West may find a little uncomfortable, but is the stark reality of existence for millions of children across South Asia.

Another regular visitor at one of the centres is Jasmine, a bright-eyed 10-year-old who attends lessons in the morning and then heads out to sell homemade jewellery. Her father earns money climbing palm trees to harvest coconuts. Jasmine says she likes singing and playing at the centre, as well as the reading and writing sessions. By contrast, the beach is not a safe place. "There are many problems here. Sometimes people look at us strangely or tell us to go away," she says. "We also have to pay money to the police to be allowed to work here."

Staff at the centres say a recurring problem is having to persuade parents to allow their children to attend. Barna Pal is an enthusiastic 20-year-old woman who has been a teacher for two years. "The biggest challenge is when we have to go to the children's homes to meet the parents," she says. "Sometimes they say the children have to work. We say they have to attend the drop-in centre. Sometimes the child has already gone to the beach. Then I will go to the beach and try and find them."

The project in Cox's Bazar is supported by Children on the Edge, a British-based charity that is one of the beneficiaries of The Independent's charity appeal. The organisation intends to roll out three more drop-in centres in the coming weeks. If these prove a success, the plan is to expand the scheme even further.

"Children face grinding poverty throughout Bangladesh. Access to education is limited in many parts of the country, especially to children who must also work. Cox's Bazar, which serves as a hub for the fishing, shrimping and tourist industries, attracts a high concentration of working children as families migrate to the area seeking employment," says John Littleton, the group's Asia programmes manager. "As a result, there is a particularly high concentration of children under 18 years of age who cannot access traditional education."

He added: "As the area's tourist industry continues to boom, it will likely continue to attract families seeking employment in menial labour and service positions. As these jobs generally provide only subsistence wages, we anticipate that many more children will be expected to work to help support their families."

Anawer, the young photographer, bought his camera for the equivalent of £80. As he goes about his work, charging tourists 50 taka (45p) a time to take their pictures, he is already thinking of the future and putting his lessons to good use. He says: "When I grow up I want to have my own business."

The charities in this year's Independent Christmas Appeal

Children around the world cope daily with problems that are difficult for most of us to comprehend. For our Christmas Appeal this year we have chosen three charities which support vulnerable children everywhere.

* Children on the Edge was founded by Anita Roddick 20 years ago to help children institutionalised in Romanian orphanages. It specialises in traumatised children. It still works in eastern Europe, supporting children with disabilities and girls at risk of sex trafficking. But it now works with children in extreme situations in a dozen countries – children orphaned by AIDS in South Africa, post-tsunami trauma in Indonesia, long-term post-conflict disturbance in East Timor, and with Burmese refugee children in Bangladesh and Thailand. www.childrenontheedge.org

* ChildHope works to bring hope and justice, colour and fun into the lives of extremely vulnerable children experiencing different forms of violence in 11 countries in Africa, Asia and South America. www.childhope.org.uk

* Barnardo's works with more than 100,000 of the most disadvantaged children in 415 specialised projects in communities across the UK. It works with children in poverty, homeless runaways, children caring for an ill parent, pupils at risk of being excluded from school, children with disabilities, teenagers leaving care, children who have been sexually abused and those with inappropriate sexual behaviour. It runs parenting programmes. www.barnardos.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments