Appeal: Raped by the enemy, shunned by friends

The 'bush wives' were the forgotten victims of Sierra Leone's civil war. Now their plight is being addressed.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Saidata Forna is not sure of her exact age. But she was less than 15 when she was captured by rebel soldiers during Sierra Leone's civil war in the dusty town of Makeni in the centre of the country – and turned into a sex slave.

Her captors were members of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), whose trademark was the amputation of the hands of innocent civilians. They took the teenager out into the bush to the village of Yelisande, and held her in bondage.

"I was raped," she recalled. "And I was beaten when I refused to conform to some of their demands. I was raped almost everyday."

After a year in captivity Saidata fell pregnant and was able to escape. However, she and other girls abducted by the RUF were not made welcome on their return to their home town of Makeni.

"We were stigmatised, we were called all sorts of names," she explained. "They said 'junta wife', 'military junta'."

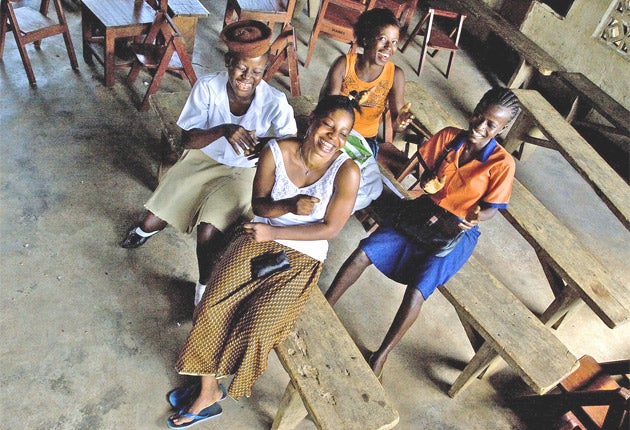

But eight years after the end of hostilities, Saidata, now 23, has made a remarkable recovery. Aided by an organisation called Help a Needy Child in Sierra Leone (HANCi) – which is funded by ChildHope, one of the three charities in this year's Independent Christmas Appeal – she was reconciled with her parents and continued her education.

"I have just completed college [at the] northern polytechnic in Makeni," said the young woman, wearing a neat purple dress trimmed with pale ribbon. "I got my teacher's certificate. I am now looking for a job."

Sierra Leone's civil war lasted for more than a decade, from 1991 to 2002, and left some 50,000 dead. Fuelled by the west African country's fabulous diamond reserves, the conflict was characterised by extreme brutality.

Conscription of children was widespread on all sides. Yet, while images of wide-eyed boy soldiers with Kalashnikovs became the international face of the war, the fate of the young women who were abducted by the rebels is less well known.

When the RUF attacked villages they would customarily take girls – sometimes aged 12 or even younger – with them as booty. While some took up weapons, most "bush wives" carried water and cooked for the men. They were also repeatedly raped.

"There were many girls among the group," remembered Yeniva Mulai, who is now 20 and believes she was nine or ten when rebels captured her. "We were raped so many times."

"Well over 10,000 to 15,000 girls were with the rebels, countrywide," said John Kargbo, HANCi's regional co-ordinator. "All those rebels wanted to be with the girls."

The bush wives were left out of the UN-brokered disarmament and re-integration programmes at the end of the war. In order to qualify for the camps and resettlement payments fighters had to hand in a weapon. The unarmed women whom the rebels had kept could not. They also found that their home communities were hostile towards them – especially those who had borne children by rebel fathers.

"I was afraid," explained Binta Sharkah, a Makeni woman who initially refused to take in her daughter after she returned from the bush.

"I felt that the rebels would come to collect her again. You know they had guns, they had everything, they had power. People were saying 'Mammy Binta's daughter is a rebel wife'," she added.

With the girls facing a parlous future in a shattered, post-conflict country, HANCi came to their aid. The local NGO originally set up an orphanage for war victims in Makeni in the mid-1990s.

But when rebels overran the town two days before Christmas in 1998, ushering in three years of chaotic misrule, the orphanage ceased operation. After the end of hostilities in 2002, HANCi was able to return and set up a programme for the so-called "girl mothers".

"During the war, young girls were captured by the rebels and taken to the bush," said Fatu Conteh, the organisation's project co-ordinator. "After the war, these girls were left out on the streets of Makeni."

The HANCi programme concentrated on counselling the traumatised young women, seeking reconciliation with their estranged parents, and returning them to school or other training. An early trial expanded following a partnership with the UK-based charity ChildHope.

"It is important to reintegrate these children as otherwise they will be further marginalised and continue to be placed in situations of violence and abuse," said Vicky Johnson, head of partnerships and programmes at ChildHope UK.

Following a lobbying campaign, HANCi was also able to strike a deal with local school administrators to allow girls with babies to attend classes, which was previously forbidden.

"We drew up a memorandum of understanding for the school authorities to accept them," said Adolf Farma, the organisation's psycho-social, educational and tracing officer.

As the original bush wives grew up and reintegrated into society, the project broadened its scope to minister to the wider problem of street children in Makeni. A survey earlier this year revealed that there are more than 400 in the town.

Many of the street girls resort to prostitution, turning tricks at grubby drinking dens where sex sells for a maximum of 10,000 leones (£1.50).

Bai Shebora Kasangna II, paramount chief of the Bombali Shebora chiefdom, which includes Makeni, is concerned about the street children.

"As paramount chief, you want everybody to be taken care of," he said. "If not, these are people who will grow up to be what the rebels were."

One of the beneficiaries of the current HANCi programme, that includes 120 girls, is Aminanta Mansaray, 16. "I went to the streets because my parents are poor," she said. "They could not afford my basic needs. They could not afford my school fees. While I was on the streets I got involved in prostitution."

Now back in school and reunited with her parents, Aminanta hopes to become a lawyer. "I would like to help my colleagues," she said.

Altogether since the end of the war in Sierra Leone around 900 girls have passed through the HANCi's programmes in Makeni.

On a recent hot Friday afternoon current beneficiaries were training at the town's Afro-Genic hair salon, learning the braiding, weaving and other complicated mechanics of African haircare.

The following day the girls, some carrying small babies, attended a morning lecture at the organisation's compound on HIV/Aids awareness. Education officer Adolf Farma delivered the talk in Krio, Sierra Leone's extraordinary lingua franca in which health is wellbodi and a pregnant woman ummanbelleh – literally "woman belly".

Despite the re-integration achieved by the HANCi programme, some of the graduates – notably the former bush wives – are still mentally scarred. They look into the middle distance as they speak about what happened to them, as though they are talking about someone else.

Others deal with the past differently. Memunata Koroma, a striking 25-year-old, was captured by the rebels when they brought their bush war to Freetown in January 1999, in a millenarian orgy of violence that marked the nadir of the whole conflict. Marched through the bush to Makeni, she was kept captive and fell pregnant.

Now she has trained as a dressmaker, but says she does not want her seven-year-old daughter to know the facts of her parentage.

"I would not like to explain the details of what I went through to my child," Memunata said. Childhood innocence, she knows from bitter experience, is too precious for that.

The names of the girls and young women have been changed to avoid hindering their re-acceptance into their villages and communities

The charities in this year's Independent Christmas Appeal

Children around the world cope daily with problems that are difficult for most of us to comprehend. For our Christmas Appeal this year we have chosen three charities which support vulnerable children everywhere.

* Children on the Edge was founded by Anita Roddick 20 years ago to help children institutionalised in Romanian orphanages. It specialises in traumatised children. It still works in eastern Europe, supporting children with disabilities and girls at risk of sex trafficking. But it now works with children in extreme situations in a dozen countries – children orphaned by AIDS in South Africa, post-tsunami trauma in Indonesia, long-term post-conflict disturbance in East Timor, and with Burmese refugee children in Bangladesh and Thailand. www.childrenontheedge.org

* ChildHope works to bring hope and justice, colour and fun into the lives of extremely vulnerable children experiencing different forms of violence in 11 countries in Africa, Asia and South America. www.childhope.org.uk

* Barnardo's works with more than 100,000 of the most disadvantaged children in 415 specialised projects in communities across the UK. It works with children in poverty, homeless runaways, children caring for an ill parent, pupils at risk of being excluded from school, children with disabilities, teenagers leaving care, children who have been sexually abused and those with inappropriate sexual behaviour. It runs parenting programmes. www.barnardos.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments