Shabaz Ali: How this humble chemistry teacher is exposing the empty lives of the super-rich on TikTok

Born in Blackburn, Shabaz Ali is best known for his comedy persona ‘Shabaz Says’, in which he uses his sharp Northern wit to perform brutal takedowns of influencers who show off online. Dubbed a modern-day Peter Kay and the ‘Robin Hood of TikTok’, he tells Zoë Beaty that when some of his pupils are struggling to eat, there is a serious point to be made

On today’s episode of I’m Rich, You’re Poor, Shabaz Ali is taking a trip down memory lane – or, rather, through the hilly streets of Blackburn, where he grew up and later became a social media sensation. It’s unusual for this teacher turned online star to start to look back – quite the opposite. He’s risen through the ranks of TikTok by giving his 1.9 million followers a much-needed reality check.

Better known by his handle @shabazsays, Ali is loved for his “I’m rich, you’re poor” deadpan takedowns of the super-rich influencers showing off their “hard-earned generational wealth”, all delivered from his bed and dispatched with a dry northern wit.

He’s basically a star now – but, as anyone who’s followed him for any length of time will understand, the most surprising thing about meeting Ali in the flesh is that he’s upright and dressed. He only left his duvet today, he says, to pick me up from Blackburn station. “After this, I’m going straight back to bed too,” he laughs.

It’s where he accidentally launched his second career as an influencer when he arbitrarily posted a video lying on his side, snuggled in a hooded onesie, talking to the camera as though on FaceTime with a friend. “People loved it because they were like, this is what I’m doing [scrolling in bed],” he says. “I think people just assume I’m in there all the time. But I do get out sometimes – I have to work.”

Ah, work. Ali came up with the idea for Shabaz Says during his beloved day job as a chemistry teacher at a local school in Blackburn. It was witnessing pupils on free school meals, from families who were struggling, watching videos of rich people with “pretend perfect lives” as entertainment that fascinated him.

“They had a warped sense of reality,” he says. “When I was a kid, I was obsessed with celebrity. But back then there was a disconnect between them and you. We all grew up wanting stuff we didn’t have or couldn’t afford, but you quickly got over it. Now, if you don’t have it, you scroll, scroll, scroll through hundreds of people telling you that they have it and you don’t.”

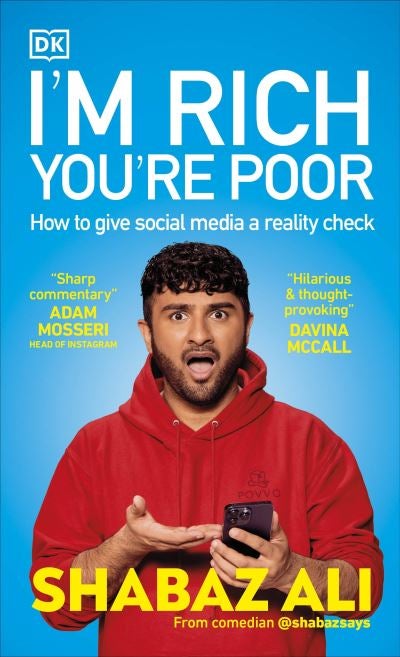

Ali’s popularity was born out of a series he began filming in early 2022, titled I’m Rich, You’re Poor – also the name of his newly released book – in which he narrates a working-class perspective on increasingly ostentatious displays of wealth on social media.

The targets of his ridicule are parents posting gastronomic packed lunches and unrealistically perfect morning routines, and influencers and creators who play into the idea that life must be perfect – and expensive – to be valued.

He’s perhaps best known for his pitch-perfect reactions to #IceTok, a plainly baffling world within TikTok where (mostly) women spend inordinate amounts of time “restocking” enormous freezers with elaborate, sometimes flavoured, ice cubes.

“I’ve got so much money that I’m buying things that I probably don’t need, but I’m rich, so I can,” he says in one of his most popular videos, in which a person can be seen embossing giant cubes of ice with various patterns. “You worry about your gas and electric, and feeding your children, when I can go out and buy things like this.”

Ali’s narration – performed in a heavy Blackburn accent, with plenty of northern phrases like “give over” and “have a day off” – is funny, but it’s about more than humour. It’s a digestible comment on overconsumption and the social politics of class, wealth and worth as told by social media and wider society.

On TikTok or Instagram, he says, if you’re not rich enough in time or money to make pentagon-shaped ice cubes for your coffee, decant everything you own into jars, or buy a $4,400 (£3,500) Balenciaga bracelet that looks (literally) like a roll of Sellotape, it’s “because you’re a povvo [a slang term meaning someone who is poor]”.

His content is a digestible comment on overconsumption and the social politics of class, wealth and worth as told by social media and wider society

Taking a stand for common people means Ali has been lovingly dubbed the “Robin Hood of TikTok”, and “King of the Povvo gang”, stealing power back from social media luvvies.

To be clear, Ali has no problem with people buying nice things or being wealthy, but he does have a problem with “showing off about it” and perpetuating the societal shame that comes with being poor – or just ordinary.

But exactly how “ordinary” is Ali, now, as a bonafide influencer himself who is regularly offered brand deals for “ridiculous amounts of money” and invited to red-carpet events? At school, after being briefly excited about his internet fame, his pupils are not too bothered these days and he’s gone back to being “Sir”, teaching them chemistry and running the school’s social media safety programmes.

But when it comes to being offered influencer deals to promote products, he’s the first to bring the somewhat uncomfortable dissonance to the table – which is in Blackburn’s shopping centre, where he’s sipping a strawberry milkshake and eating an m&m’s muffin.

“In good faith, I cannot ask working-class people to go out and buy something they couldn’t afford. I do adverts,” he continues – his first was a duet taking the “new” Fanta down in his signature style, which admittedly felt on-brand.

Although he says he turns things down that don’t align, Ali has been criticised for “lying” about his working-class status when he wears fancier clothes, and seems worried about being seen as disingenuous. “There is this mentality that you shouldn’t have nice things if you’re a povvo. But ‘povvo’ is a mindset and it’s a movement – it’s not always a monetary thing.”

Ali shows me the house he grew up in – a three-bed mid-terrace on a terrifyingly steep hill, where the parks he played in are now rubbish tips. He now lives with his mum, his dad (a taxi driver), his brother, his sister-in-law and his niece in a rented house nearby.

“My parents had to sell that house when they ran into a bit of financial difficulty,” he explains. “They don’t really talk about it... I think it makes them too sad.”

Though being an influencer could now be his full-time job, Ali has no plans to leave teaching, where he says he “first found acceptance” – something he’s struggled with throughout his life.

“Me and my preteen self are basically the same person – so fun, carefree... And then in my teenage years, you just see this kid in the corner that doesn’t want to take pictures,” Ali says as we pull up by his former grammar school. “I was bullied for when I didn’t have enough money; for my hair, because I had a middle parting – King Charles, they used to call me – then I was ‘too girly’, or ‘too dark-skinned’.

“Colourism is massive in our community; they always said to me ‘Oh, he’s dark-skinned, he’s never going to amount to anything.’ It didn’t bother me, but subconsciously it must have seeped in.”

For a long time, he felt “unlovable” and like an imposter. “I think, being working class, you always have that feeling of imposter syndrome,” he says. Despite his accent and class now being key elements of his persona, he has struggled to accept them himself.

“I moved to London when I was 18 to go to university. Back then I hated my town and I hated my accent,” explains Ali. It annoyed him that people assume “northern” comedy is “thick”. “I got sick of people mocking it, so I just thought I’d try and mute it. And then I grew up. Now I’m so proud to be working class, and so proud to be from Blackburn. I realised that there used to be a real sense of community about being working class.

“The best thing [about my content] is that people talk to each other in solidarity in the comments; they’re proud about the fact they can’t have these things or that they’re not engaging with overconsumption.”

His new book I’m Rich, You’re Poor is in some ways a rallying cry for contentment. It’s not a literary work, but it does contain some astute observations – how it used to be commonplace to hide one’s wealth from those less fortunate, for instance.

“Rich people have always been aware that if they annoy us enough by dangling beautiful things in our faces, we’ll have a revolution,” he writes; now it’s weaponised shame that keeps us quiet.

The book also touches on the housing crisis, growing inequality, the class identity crisis and food scarcity. Each section is peppered with tips familiar to anyone with a working-class background – never buying at eye level in the supermarket, buying per kilo not by offers, leaving the oven door open when you’ve cooked “because you’ve already paid for the heat”.

At a time when the cost of living crisis is still biting, few solutions are being offered and a general election is looming, could Ali’s book help to usher in a new, fairer government? It definitely can’t hurt.

This is a book that is breaking down political and social ideas, and delivering them with a soft landing to a readership that is, in all likelihood, not particularly engaged with what’s going on in Westminster.

On the way back into town, we chug up an intimidating hill – all 427ft of it – towering over church steeples and the northwestern moorlands where Ali, King of the Povvos, reigns. For now, Shabaz Ali is exactly where he needs to be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments