On a long car journey last week, my son and I began a discussion about our favourite pasta sauces. It was, I suggested, hard to beat a really good bolognese – one baked for hours in the oven, made with soffritto and plenty of plonk. The eight-year-old in the back was unimpressed, despite spag bol being his regular Friday tea for most of his life. Carbonara or puttanesca were his top two, with pesto nudging into third spot above bolognese and a plain tomato sauce.

As a favourite five, that seemed decent, though I made a plea for a sausage, fennel and broccoli combo, and argued that the tomato sauce would benefit from the addition of some chilli. If the pasta is freshly made, I’d also be very happy with a simple butter and sage sauce. The boy thought he’d give it a try.

Had you heard this greedy conversation, you might think my son was an adventurous gourmand, eager to try new flavours, and excited by the glorious culinary possibilities offered by the world. And were he an Italian bambino, scoffing pasta or pizza for every meal, your impression might be borne out.

But in the UK, it can be hard to guarantee that a visit to family or friends will be accompanied by a steaming bowl of fusilli alla napoletana or linguini alla arrabbiata. And when faced with something unfamiliar or unfavourable, my son’s relish for his dinner vanishes immediately.

When this happens as a one-off, it can generally be laughed away. A great uncle we see once in a blue moon probably won’t notice (or remember) how the spread he has busied himself with all morning is greeted with sounds of mock vomiting from his youngest guest. And friends might be bemused that a small boy doesn’t like sausages, but they’ll probably be happy enough to let him eat five pieces of bread and butter if that’s really all he wants.

Naturally, even these solitary occasions provoke significant embarrassment for his parents, despite both of us having had our fusspot moments as children. What’s worse though, is when we realise our kids have gained a reputation for their singular eating habits.

This is particularly true among close family members, who regularly have to make their way through the munchy minefield when our offspring come to stay. My mother has borne an especially heavy burden. On the one hand, she has had the irritation of discovering that items she reasonably assumed were fail-safes – burgers, fish fingers, mash – are in fact detested by at least one grandchild. Even worse, it has turned out that things we told her the children liked – pizza, chicken, peas – get the thumbs down because they’re not quite the same at her house as they are at home.

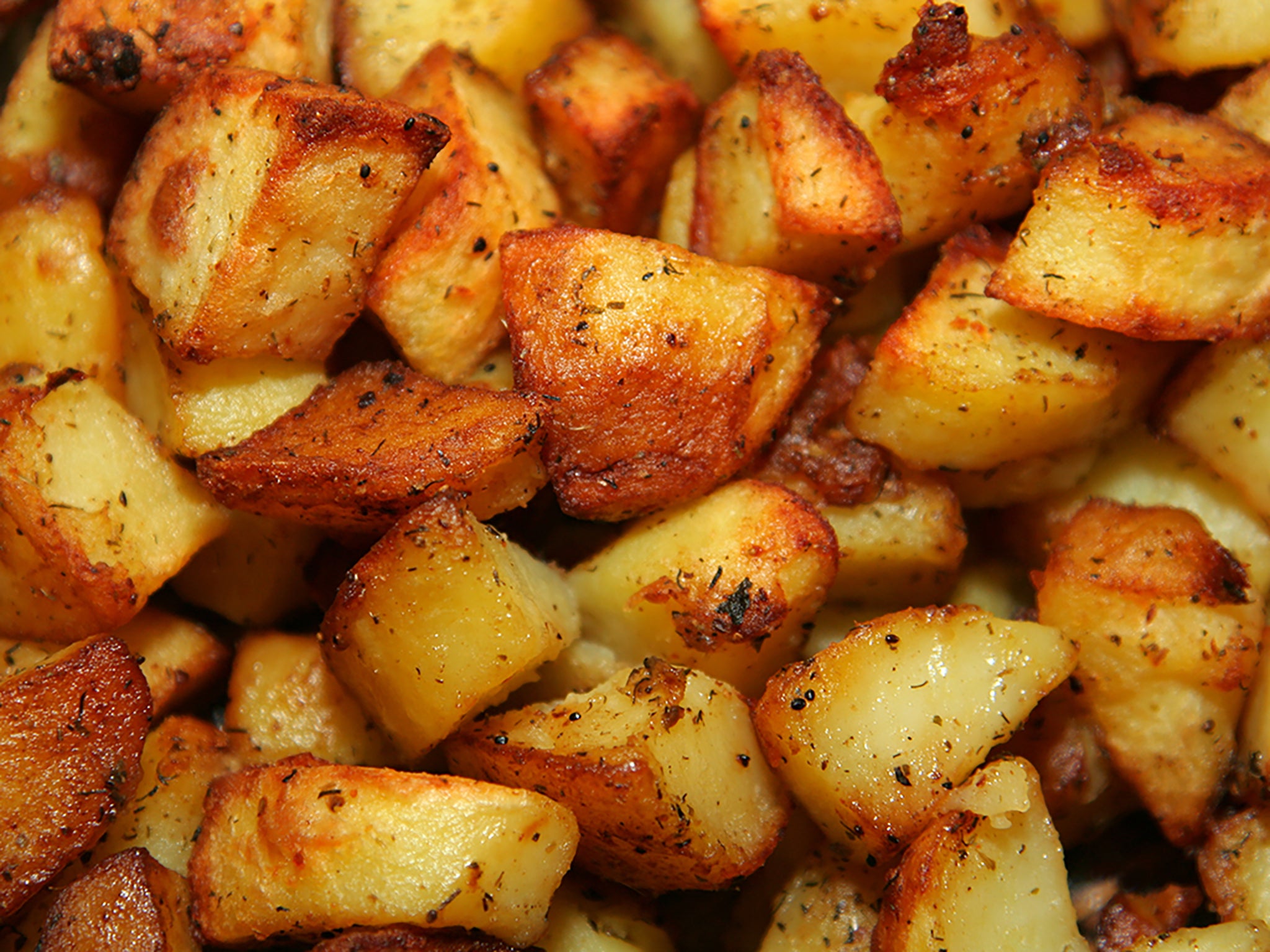

Roast potato-gate epitomises the problem. At home, my son will merrily put away four crispy King Edwards. But at granny’s, he’ll grumble that the variety isn’t the same or that they’re too soft. And the gravy isn’t right. His sister was once just as bad, but at least she now understands the need to be polite and worry things down. My son will simply say in a stage whisper when I try to jolly him along, “but it’s disgusting”. Cue a thunderous look from granny.

Having persisted in their attempts for years, our close family have more or less thrown in the towel. Sometimes a plea might be made that we bring with us something the children will eat – mummy’s spag bol. Otherwise, they’ll cave in to the kids’ worst whims. Cheese wraps for every lunch, and dinners of pancakes, plain pasta, and eggy bread (possibly with a Kit Kat on the side). And in all the circumstances, who are we to argue?

And yet of course we wonder where we went wrong. When they were first weaned, both our children seemed to set a course for culinary experimentation: our daughter’s first non-baby food was some mushed-up pork and cider stew, and our son used to try anything and everything. Yet at my brother’s house last week, he nearly hurled at the prospect of some potato and cauliflower curry, and in response to being offered a fruity fromage frais, he shouted angrily: “I hate yoghurt!” They might have guessed.

All this from a child who on the same day told me that eating was his favourite pastime. True, he was working his way through a handful of chocolates at the time, but maybe it’s the thought that counts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments