The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How to tell if your name matches your face

Do you look like a Bob or a Peter?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some people just seem to look so much like a Steve, Lucy or Hugo. But is there really such a thing as faces matching names?

New research has found that people do believe some faces and names go together, and we prefer it when they match up.

People with round faces should have names that sound round, the study found. A name like “Bob” or “Lou,” which requires a rounding of the mouth, for example.

And people with more angular faces go better with similarly angular names, like “Peter.”

Researchers from the University of Otago in New Zealand tested their theories by having people look at pairs of names and faces.

Some of the names matched the faces, others didn’t, and people apparently preferred it when they matched.

The researchers took the study further and found that people are more likely to vote for political candidates whose names match their faces too.

“Those with congruent names earned a greater proportion of votes than those with incongruent names,” lead study author David Barton said.

They analysed data from Senatorial election in the US.

“The fact that candidates with extremely well-fitting names won their seats by a larger margin - 10 points - than is obtained in most American presidential races suggests the provocative idea that the relation between perceptual and bodily experience could be a potent source of bias in some circumstances,” Barton explained.

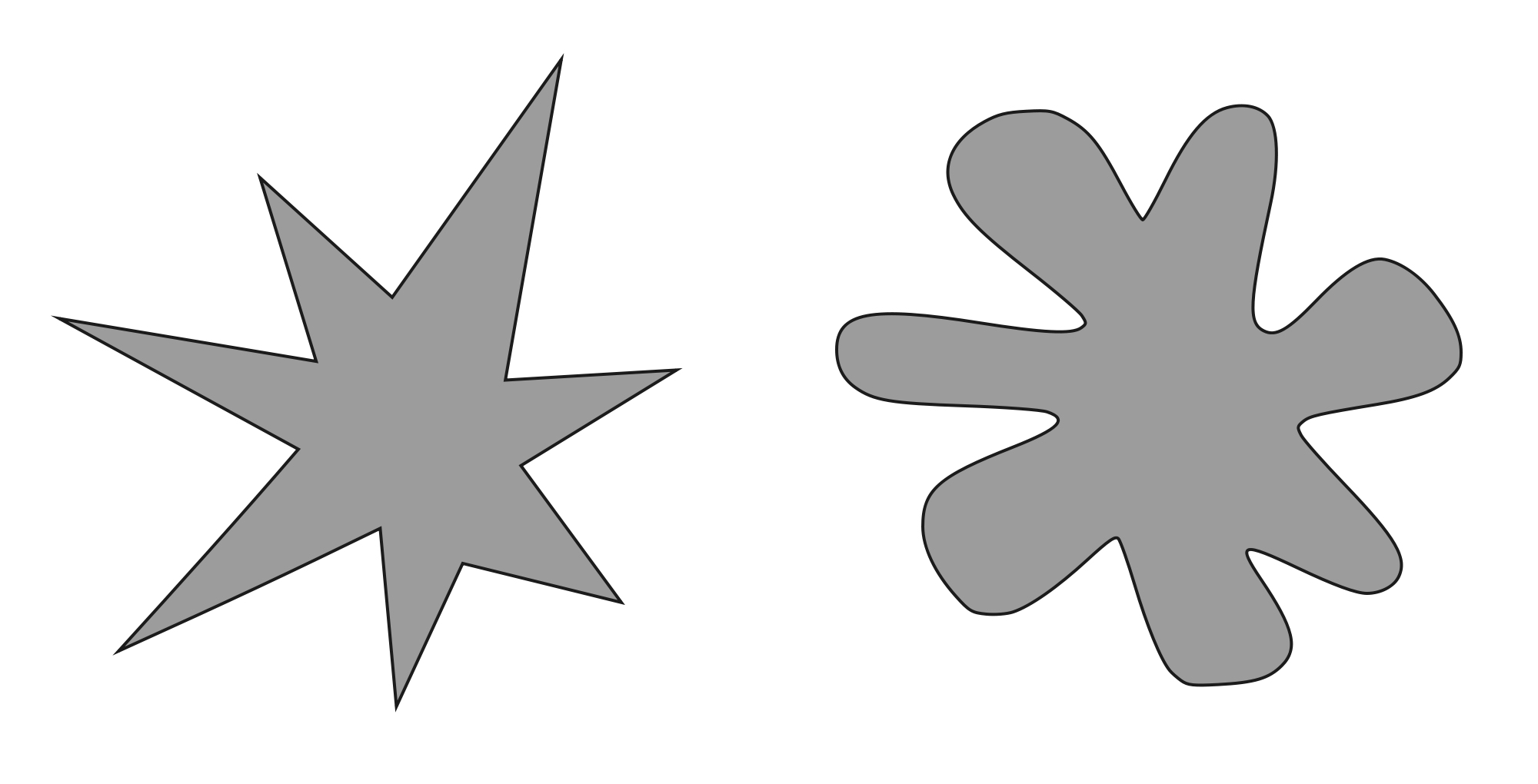

The study was inspired by what is called the “bouba/kika effect”.

This theory says that when shown the above two shapes and asked to match each one either to the name “bouba” or “kika,” over 95 per cent of people choose “bouba” for the rounded one (right) and “kika” for the spiky one (left).

And it works in various languages too - one study found Tamil speakers in India did the same.

Professor Jamin Halberstadt, who co-authored the study concluded that their results tell a consistent story:

“People’s names, like shape names, are not entirely arbitrary labels,” she said.

“Face shapes produce expectations about the names that should denote them, and violations of those expectations carry affective implications, which in turn feed into more complex social judgments, including voting decisions.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments