Asexuality: when life isn't all about sex

Research suggests 1% of the population (more women than men) are asexual. But the majority of people may view asexuality more negatively than other sexual minorities, and it has been identified as a 'sexual disorder' in the past

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

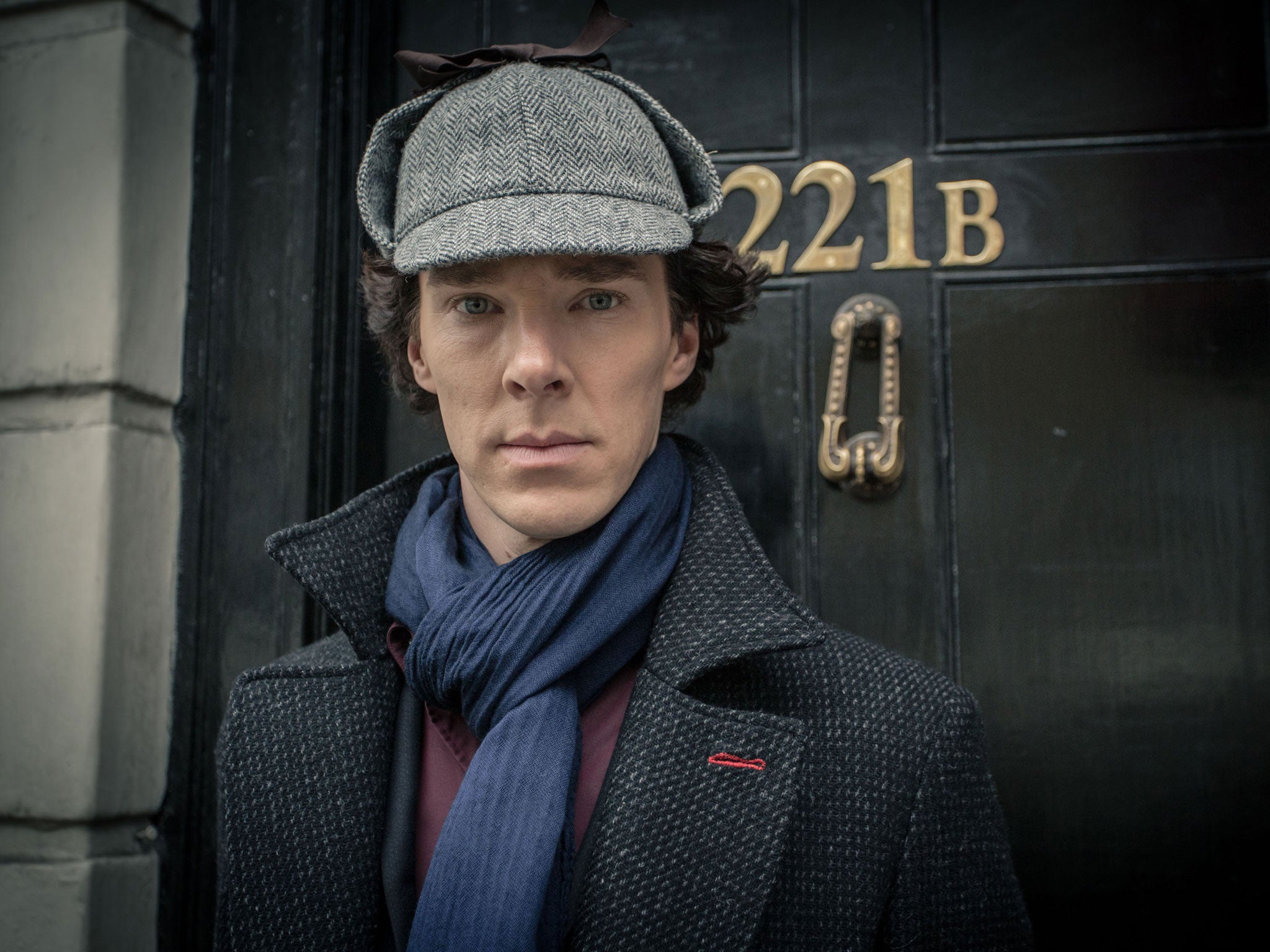

Your support makes all the difference.Though asexuality isn't something which is often discussed in the media, it is used in entertainment: think Sherlock Holmes eschewing of all things sexual and thus adding to the dramatic portrayal of the character’s single-minded pursuit of intellectual truth, or think Sheldon in Big Bang Theory brushing up against a sexualised world and thus ramping up the comedic tension in the sit-com.

In the modern, real-world incarnation of the no/low sex spectrum we find asexual people, a group increasingly interested in “coming out” and staking their claim on the social landscape. A defining feature of asexuality is little or no sexual attraction to other people - in short, no lustful lure for others.

Not surprisingly, many asexual people also exhibit very little sex drive or sexual interest whatsoever (including no masturbation), although some may still have some “solitary” desire. Thus, some asexual people may still evince some sexual drive but it is not connected to others.

Recent research has suggested that perhaps as many as one per cent of the population—with more women than men—are asexual. Research also suggests that the origins of asexuality, like traditional sexual orientations, are at least partly rooted in early development.

Researchers have also begun to examine a variety of issues related to asexuality, including how some asexual people are content to “fly under the radar,” socially speaking, while others may form a strong asexual identity and “come out” to others, and how asexual people may be the subject of prejudice and discrimination. In the latter case, recent research suggests that the sexual majority may view asexual people more negatively than other sexual minorities.

Asexual people, particularly if they are comfortable with themselves, have also recently challenged health professionals, including writers of the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (or DSM), as to what it means to have a sexual disorder. For example, there is now a provision in the recent DSM that allows self-identified asexual people to avoid being diagnosed with having a sexual disorder.

As I suggest in my book, Understanding Asexuality, there are many reasons why those interested in sex—including sex researchers/educators—should try to understand asexual people and their view of the world. First, studying asexual people provides information on a relatively unstudied group, and knowledge of this minority may help asexual people understand themselves better and ease their negotiation through a complex and foreign sexual world.

Studying asexuality also provides a unique window on sexuality and its mysteries, including its complex relationship to love and romance. For example, although some asexual people do not want romantic relationships—one person on AVEN, the most popular online forum for asexual people, writes succinctly “Never had a relationship, never want one” — many asexual people desire romantic relationships, even if they eschew sexual ones. Another AVEN participant writes: “I am now in a relationship with a heterosexual person, I don't know how it will work out but I am trying to be positive about it and keep the focus on what we have in common rather than what we don't have in common…”

Given that asexual people often want a romantic relationship (despite its challenges), they provide a model of how romantic love can be de-coupled from sex, and such a model also holds for sexual people. Indeed, the popularity of movies in the bromance genre—e.g. two (burly) straight men forming a deep bond— demonstrates the usefulness of the romance versus sex model of human attachment.

Examining asexuality also can afford a clear view on how deeply infused sex is in our society—from the pervasiveness of sex in the media to our enduring interest in gossip on the sex lives of others. We also may begin to see more clearly the strange and often mad complexity of sex, with its jealousies, obsessions, and distortions of reality. Sex is unquestionably part of the great story of human life—our means of reproduction and a deep source of passion and pleasure for many—but it is also a strange and mad world at times, and one that is better understood if we take a glimpse or two from the outside.

Anthony F. Bogaert, PhD, is a Professor at the Department of Health Sciences, and Department of Psychology, at Brock University, Canada. His latest book is Understanding Asexuality

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments