Live-streaming has a dark side that no one seems able to stop

In an interview last month about Facebook’s recent push into live streaming video, chief executive Mark Zuckerberg repeats the word “raw” like it’s some kind of sacred totem. Facebook Live is “raw and visceral,” he says. It’s this “new, raw” way to communicate.

Zuckerberg doesn’t seem to realise that, when it comes to online video, “raw and visceral” — from viscera, which literally means guts (!) — can be a very bad thing.

In the weeks since, a woman live-streamed her suicide, a teenager broadcast her friend’s rape and a man narrated his standoff with a Florida SWAT team. So it’s safe to say that Zuckerberg and other champions of the live-stream revolution are wising up to what “rawness” actually means.

Rawness is fast emerging, in fact, as the central paradox of live streaming: The very intimacy and immediacy that make the medium attractive are also the things that make it almost impossible to keep clean.

“These are real-time messages,” said Emmett Shear, chief executive of Twitch, where a man recently broadcast audio of himself beating his partner and a high-profile gaming tournament was drowned out by a racist comments stream. “This isn’t like Facebook posts that get to sit there for a few hours. This is like, you gotta be on it 30 seconds after they posted it, because that’s the entire window of impact.”

These are still early days in the live-stream revolution, of course, and everybody emphasises that they’re still working out the exact mechanics. Shear’s Twitch, a four-year-old site popular among gamers, only really hit the big leagues when it was bought in late 2014 by Amazon.com. Periscope, a mobile streaming app owned by Twitter, launched just over a year ago in March 2015. And Facebook Live, that network’s big push into streaming video, is only just wrapping up its eighth week.

For even these newborn platforms, however, the need to nail down moderation is particularly urgent. On asynchronous networks, like Reddit, Twitter and Facebook, content accumulates an audience over time – people see a tweet or photo only as it gets passed around. On Twitch or Periscope, however, the vast majority of a stream’s total audience will see footage, even graphic footage, the moment it goes out.

On top of that, while there’s no research on streaming video specifically, there’s plenty of research to suggest that graphic, widely circulated media can have a dangerous public-health effect: Videos about gun violence or self-harm tend to be “contagious.”

In one disturbing incident on May 9, 30-year-old Adam Mayo barricaded himself in his house and sent a series of nine live broadcasts showing his armed standoff with Tampa police. Despite the fact that Mayo brandished a handgun, and repeatedly promised to start shooting — “Miss,” he yells at one point, “you got a body bag ready?” — Facebook moderators didn’t step in to shut down the stream.

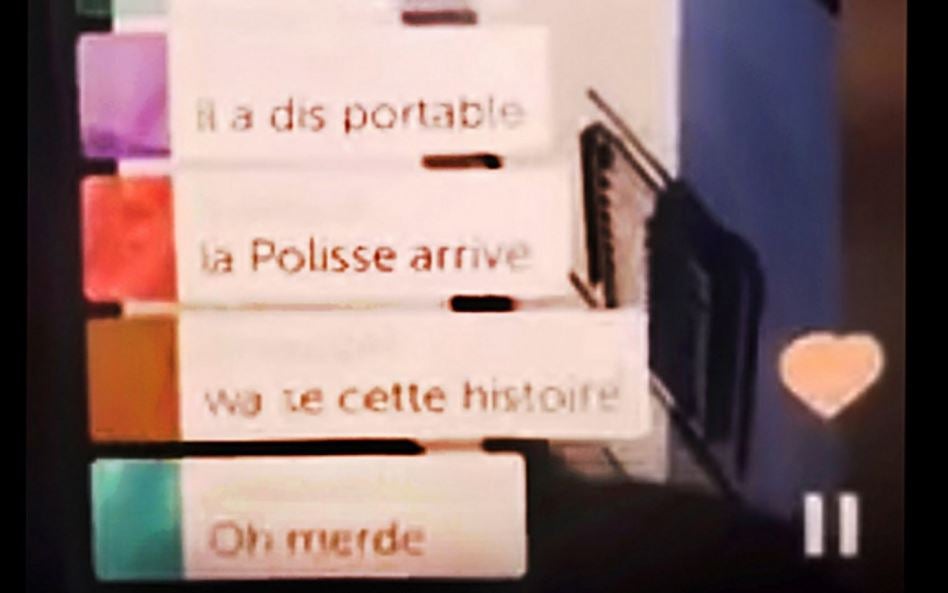

A day after that, on May 10, a 19-year-old French woman used Periscope to broadcast the hours leading up to her suicide, as well as the event itself. In truncated archives of the video, still available on YouTube, the feed is eventually cut by a frowning man who looks like an emergency worker. In the comments that bubble across the screen, some viewers wonder why the stream was not ended sooner.

Periscope did not agree to elaborate on the details of that delay or the specifics of its moderation process generally — nor did any of the other platforms The Washington Post approached for comment for this article. But both Periscope and Facebook Live — and, to a slightly lesser extent, YouNow and Twitch — rely primarily on reports from users to alert moderators to violence.

That means that, in order for a live stream to come down while it’s still live, viewers have to be quick to flag it and moderators quick to review those flags. It would appear that, somewhere in that system, there’s still quite a dangerous bit of lag.

This can be improved even if there’s no perfect solution. (Shear likens the problem to a gardener battling weeds: You can spray plenty of Roundup, but you won’t get all of them.) Platforms like YouNow, which is popular with teens, and thus has far more stringent rules, have developed some automated tools to bring problematic content to their attention faster. Meanwhile, Facebook has assigned a dedicated team to moderate nothing but abuse reports on Live, which can be tagged with descriptors like “violence” or “self-injury” to help moderators prioritise.

Virtually everyone is interested in regulating how live streams, once broadcast, are replayed and archived: The best defense against the next viral snuff film may be controls that prevent it from circulating again off-site.

All of this is enough to make one wonder whether the hype about live streaming is really worth it: It seems a lot of heartbreak, and a lot of risk, to see some shaky, confessional live vlogs that are euphemised as “rawness.”

But it would be a mistake to condemn the genre, argues Benjamin Burroughs, a professor of emerging media at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. After all, there is a flip side to all these horror stories: millions of live streams that make us laugh, or condense distance, or provide new and novel access.

“That ability to broadcast events in real time allows for the viewing of images and events that would otherwise be filtered,” Burroughs stressed. And for better or worse, once that image is out, there’s really no undoing it.

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks