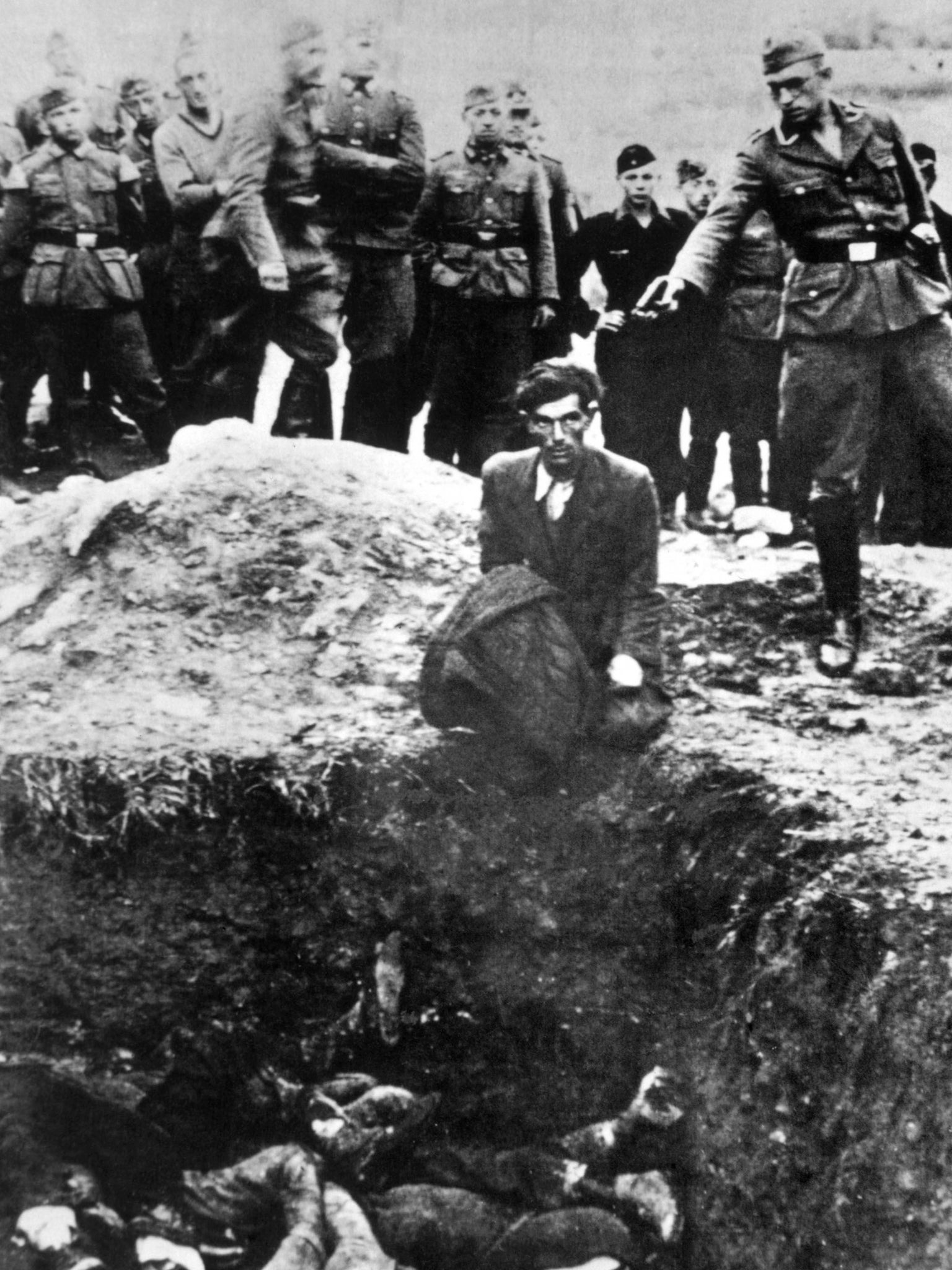

Nazi war criminals got away with atrocities because of evidence hidden in UK and US archives

Thousands of pages of documentation describe atrocities carried out in both Eastern and Western Europe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nazi war criminals escaped prosecution because crucial evidence in Britain’s National Archives and in government archives in the United States was ignored for decades.

The thousands of pages of documentation describe atrocities carried out in both Eastern and Western Europe – but have only been examined by German government war crimes investigators over the past four years, after most of the suspects and witnesses had died. At no stage had British or US intelligence told the Germans of the existence of the material.

Much of the original material was gathered when British and US intelligence services bugged a small number of prisoner of war camps near London and Washington DC during World War Two. For years the documents were kept under wraps by the intelligence services because the prisoner-of-war camp bugging program would have been regarded as illegal under international law – and, more importantly, because, during most of the Cold War, the US and Britain did not want to alert the Soviets to the fact that they had developed this intelligence gathering technique.

“All the relevant material was of course known to the British and American intelligence services during and after the war – and was in the public domain after its declassification in the US in the 1970s and the UK in 1996. However, prior to 2009, no use was ever made of the material to track down war criminals. If the direct evidence and the indirect leads contained in the material, had been used earlier by official war crime investigators, there is no doubt that a number of war criminals would have been arrested and brought to trial,” said London School of Economics historian, Professor Sönke Neitzel, co-author of Soldaten: On Fighting, Killing and Dying – a recently published book on the World War Two allied prisoner-of-war camp bugging operation.

“It is regrettable that the intelligence services in the UK and the US did not make use of the documentation and did not pass it on to the German war crime investigation authorities in the latter part of the 20th century, before many of the suspects had died,” he said.

A Channel 4 documentary – Spying on Hitler’s Army – on the secret bugging operation will be broadcast on Sunday evening.

In total some 3000 hours of clandestine recordings were made of German prisoners- of-war in UK and US PoW camps. Of those 3000 hours, up to 200 hours referred to war crimes. The US material was declassified in the 1970s, while the UK material was declassified in 1996. Professor Neitzel started his research into the material in 2001.

His first academic article was then published in 2004. In 2009 German government investigators heard that Professor Neitzel was carrying out academic research on the British and American documents and requested the material from him, which he then supplied. However, by that time, most of the suspects had died.

“In the rare cases which offered some prospects of success, our investigations ended up revealing that the relevant persons had died,” said a spokesman for the Official German State Justice Administration responsible for investigating Nazi war crimes.

Because of the illegal nature of the bugging and the wish to keep it secret from the Soviets, the material was not used in the Nuremberg war crime trials.

Commenting on what appears to have been a proposal by the British Army’s department responsible for war crimes prosecutions (the Judge Advocate General’s Branch), MI19 (the Intelligence Service section responsible for the bugging operation) insisted that the existence of the transcripts could not be revealed in any way. This precluded their use in any war crime trials – and almost certainly greatly limited their use even in investigations.

A formerly top secret, and up till now unpublished, letter written by an MI19 lieutenant colonel on 16 November 1945, found by Professor Neitzel, in the National Archives at Kew, states that the organisation considers “as of the highest importance the avoidance of anything which could draw attention to or make public the methods employed” to obtain the information.

The letter went on to say this was partly because “these methods” (ie. the bugging of German prisoners) “would presumably again feature largely in any future war” – ie against the Soviets.

What’s more, the letter pointed out that, at the time, those methods were “still being employed” inside prisoner-of-war camps by allied intelligence services outside the UK.

The letter added that MI19 wanted to “avoid at any cost” anything that might disclose “the names of [German] PoWs who have been actively working for us”.

The MI19 lieutenant colonel also made clear the advanced nature of the British bugging techniques and equipment.

The Germans “have in fact used similar methods themselves, which, however, they have never brought to that point of perfection reached by us,” says the formerly top secret 1945 letter.

Professor Neitzel also believes that British war crimes prosecution authorities were not particularly interested in pursuing relatively junior war criminals even if their crimes were extensive and horrific.

“The British were only really interested in prosecuting top generals, politicians, government officials and doctors,” he said.

Of the 10,000 prisoners who were secretly bugged, more than 300 were recorded as stating that they had participated in activities which were obviously war crimes or had witnessed such activities.

That information in turn provided evidence that may have helped identify hundreds of other German soldiers who had committed war crimes, but had not been taken prisoner.

“Churchill definitely knew about MI19’s bugging operation – but it’s not known whether the immediate post-war discussion about preventing their use in war crimes trials reached his level,” said Professor Neitzel.

The transcripts reveal information about many types of war crime, including the mass-murder of Jews, the killing of PoW’s, the slaughter of civilians in anti-partisan operations and the rape of women in Nazi occupied territories in both Eastern and Western Europe. They provide evidence of war crimes which occurred in Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Serbia, Belgium, France, Italy and Greece.

The suspects referred to in the bugging documentation – virtually all of whom have now died – include members of the Waffen SS and of the Wehrmacht – mostly from the lower ranks but including some more senior officers.

If the transcripts had been used for war crimes investigations at a much earlier stage, it’s likely that Lieutenant-General Heinrich Kittel (who died in 1969) may have faced prosecution as an alleged accessory because the documentation reveals that, when he was a colonel, he had witnessed serious war crimes – but apparently did nothing to stop them. General Dietrich von Choltitz, who died in 1966, might also have faced prosecution for his alleged role in the Holocaust, as revealed in the transcripts.

Other potential suspects died in the later 20th century and early 21st – including a Waffen SS non-commissioned officer called Fritz Swoboda who died in 2007 – just two years before the German investigators had access to the bugging operation transcripts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments