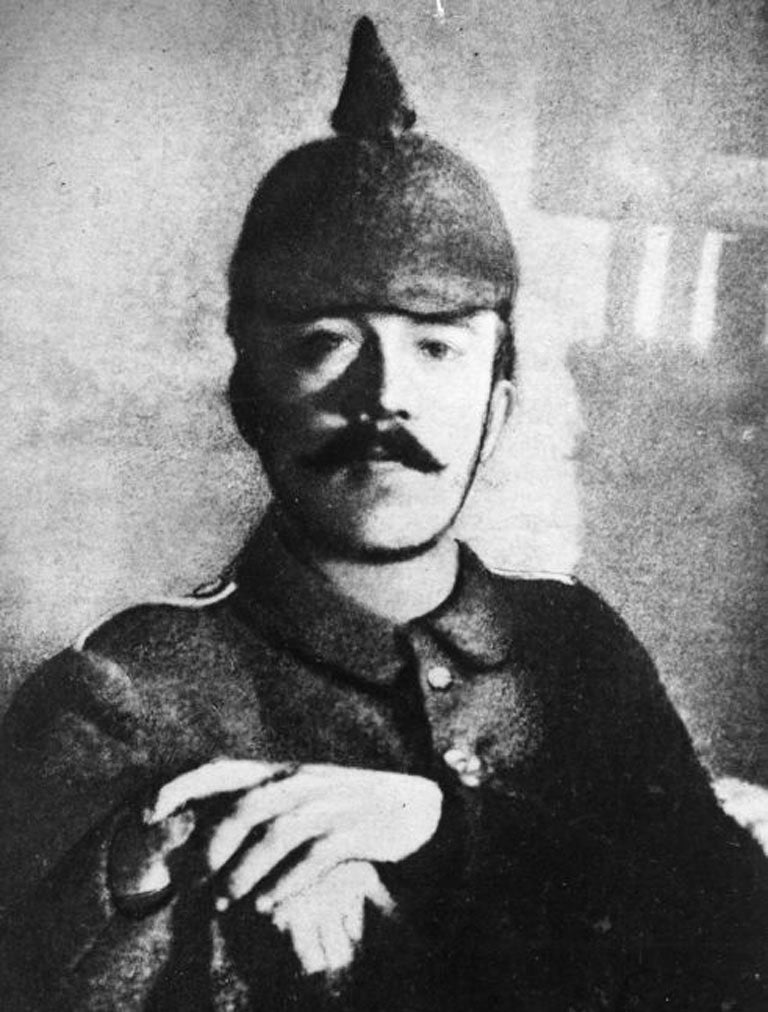

Hitler's war boast exposed as a myth

Unpublished letters disprove claim that he was blinded in action by a British mustard gas attack

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A notorious propaganda story told by Adolf Hitler about himself can now be exposed as a lie. The Führer claimed that the First World War ended for him when he was blinded in a British mustard gas attack, but previously unpublished letters reveal that his blindness was in fact caused by a mental illness – undermining the "war hero" image used to such political effect by the dictator.

Letters written by two prominent American neurologists cast serious doubts on Hitler's mental state at the end of the First World War, confirming that he was treated for "hysterical amblyopia", a psychiatric disorder known as "hysterical blindness".

The previously unseen evidence has been made available to a leading historian, Thomas Weber of the University of Aberdeen, following his acclaimed book Hitler's First War last year. The paperback edition, due out this month from Oxford University Press, will include the fresh material.

The letters, written in 1943, recall that Otfrid Förster, a renowned neurosurgeon, told each of the Americans in the 1930s that he had inspected Hitler's medical file from Pasewalk military hospital in Germany in 1918. He told them the file clearly showed that Hitler had been treated for hysterical blindness. One letter records: "Förster told me that in 1932 he was interested to look up the medical record of a rising politician called Adolph [sic] Hitler in the medical records of the German war office. He found that... the diagnosis was 'hysterical amblyopia'."

Dr Weber described the new material as "crucial" because Hitler had his medical file destroyed, and those with knowledge of it were murdered or committed suicide. Förster, neither an opponent of Hitler nor Jewish, died in Germany in 1941. Until now, there was no hard evidence to challenge Hitler's claims about the gas attack. In Mein Kampf, he wrote that the British had attacked in October 1918 south of Ypres using a "yellow gas... unknown to us". He added that by morning, his eyes "were like glowing coals, and all was darkness around me".

Dr Weber used other documentary evidence in his original book last year to dismiss Hitler's claims as a front veteran, showing that much of his time was spent as a regimental headquarters runner miles behind the lines, and that his fellow soldiers in the trenches shunned him as a "rear area pig". He also showed that members of the List Regiment thought of Hitler as an object of ridicule, a loner neither popular nor unpopular.

He told The Independent: "The two letters are so important because they confirm that we really have to look at Hitler's mental state and his radical personality change in the aftermath of the war if we want to understand the sudden metamorphosis of an awkward soldier, in whom none of his superiors had seen any leadership qualities, to a self-assured charismatic leader less than a year after the end of the war."

The two letters by the US neurologists Victor Gonda and Foster Kennedy were made available to him by one of their sons. Dr Weber said that the evidence offers radical insight into the making of Hitler and National Socialism in the trenches, contradicting the assumption that his ideas emerged before the First World War.

"The fact that he would not have been able to deal with the stress and strain of war is significant," said Dr Weber. A psychiatric disorder does explain the sudden personality change, he said.

Other new evidence brought to Dr Weber's attention following his book came from Bernhard Lustig, a Jewish veteran from Hitler's regiment who emigrated to Palestine in 1933. Lustig said that "in none of their encounters had Hitler displayed any anti-Semitic tendencies... nor any leadership qualities".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments