How Britain's 18th-century teetotal movement expressed its message through song

For 100 years or more, Britain’s temperance movement held sway. Godfrey Holmes explains how it used pulpits, badges, flyers, T-shirts – and a memorable playlist urging listeners to ban the bottle

Getting your audience to cut down on, or abstain altogether, from alcohol would, until very recently, have counted as a sure lost cause. Consider the importance of alcohol in the social life of the nation: its gathering, its partying, its eating out, its business dealings, its relaxation. Or consider the almighty strength of the alcohol lobby – so well resourced, so generously funded, so welcome in the corridors of government. A non-runner indeed.

Yet for a hundred years or more, Britain’s temperance movement held sway, not least in areas blighted by abject poverty, as well as wherever nonconformist chapels were packed to the rafters. And with the impetus came leadership; and with leadership came evangelism; and with evangelism came song.

Although John Wesley was active in the 18th century, declaring the buying, selling and consuming of liquor evils to be avoided, and although a society for the suppression of intemperance had been founded in the States in 1813, it was 1833 before Joseph Livesey formally introduced teetotalism to the heavily industrialised northwest of England though his Preston Temperance Society. Opinion is split regarding the double “T” in totalism, with some historians attributing it to one revivalist’s stammer and others noting the capital T next to many an advocate’s name, denoting temperance.

Coincidentally, the Independent Order of Rechabites was gaining popularity in Salford, a friendly society akin to the Oddfellows, Foresters, Lions and Buffaloes promoting prudence, saving, and access to healthcare and death benefits via the panel. Rechabites emulate the House of Rechab, an Old Testament nomadic tribe that would not drink wine nor build houses nor sow seeds.

In 1847 – and swept along on a tide of Victorian social reform – Reverend Jabez Tunnicliff, assisted by Ann Jane Carlile, founded easily the most influential temperance society of all – the Band of Hope union. Three-hundred children attended the first rally in Leeds, each ready to “sign the pledge” – a pledge reading: “I the undersigned do agree that I will not use intoxicated liquors as a beverage”.

In time – concurrent with the Sunday school movement with its offshoot football clubs Aston Villa and Sheffield Wednesday – the Band of Hope ran children’s meet-ups, bright hours, public talks, tented camps, festivals and pageant queens. By 1887, Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, a million and a half children – two in every 11 from Britain – had subscribed. And by 1897, the now Patron Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, the Band of Hope had an astonishing reach of 3.25 million.

Single-issue bodies – whether campaigning for organ transplants, municipal parks, quieter aeroplanes or nuclear disarmament – often struggle to speak outside the box and diversify. The Band of Hope avoided that pitfall by talking of infant mortality, child cruelty, battered wives, cleaner drinking water, social housing and shorter working hours. Admittedly, these factors sometimes related to high alcohol consumption – but at least a burgeoning temperance movement was not a one-pony stable.

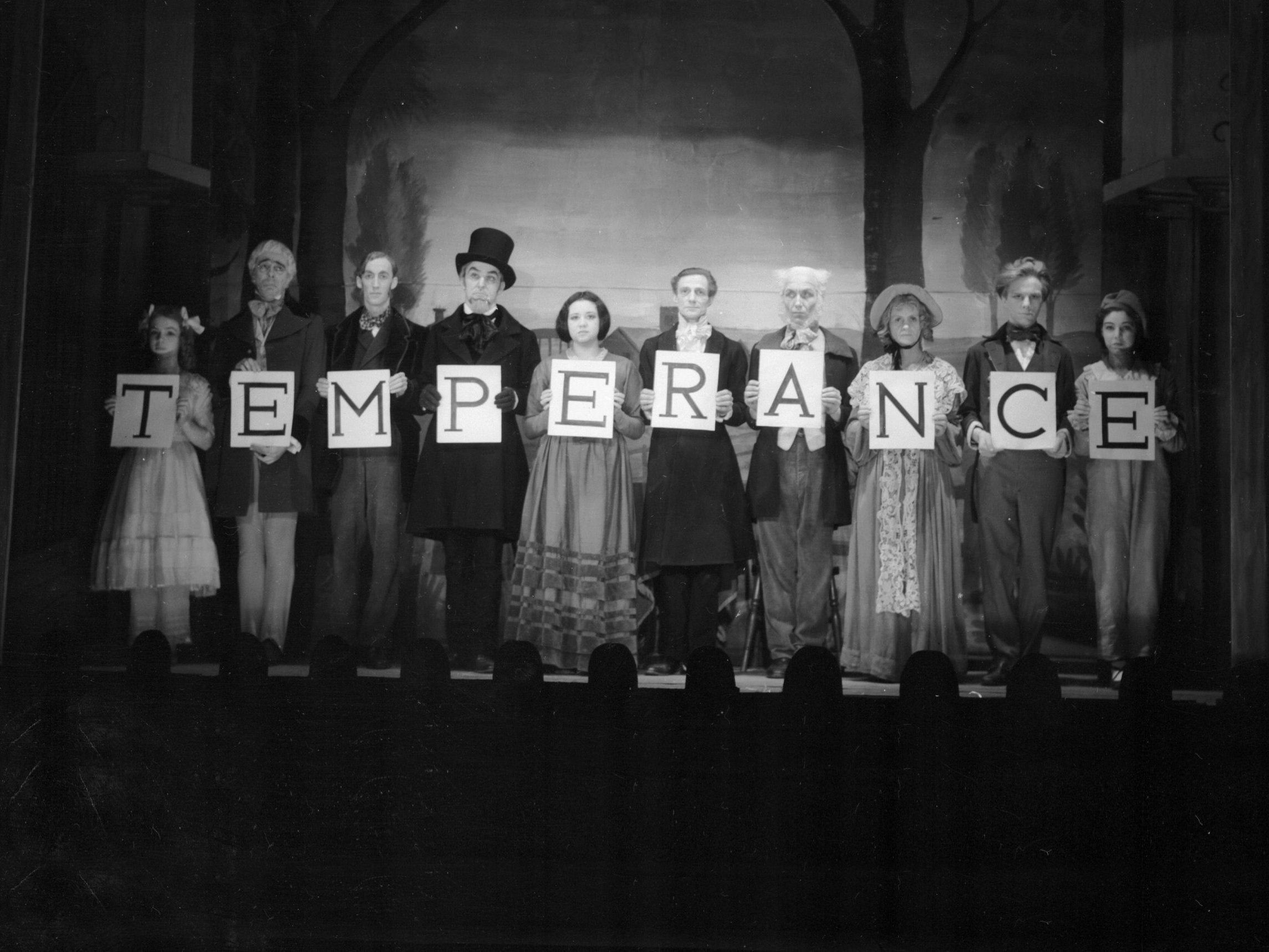

The temperance movement – in pictures

Show all 14Now to expression of belief. In a simpler world far less literate than today, the temperance – indeed abstinence – message had to confront the public boldly. The alcohol-free Salvation Army established by General William Booth in 1863 had the immediate advantage of parallel enlistment, a distinctive uniform, the dramatic rescue of lost souls, and lively citadels. Not by accident did the Sally-Ally use woven banners. In fact, banners were being stitched at a record rate that century: as extra decoration for the walls of churches and chapels; to identify Protestant from Catholic districts in Northern Ireland; to furnish numerous protest marches; to illustrate gay pride.

But pulpits, badges, scarves, flyers and T-shirts can only go so far. Music is the key to a memorable message. Again, the Salvationists were ahead of the game with their semi-professional bands performing on street corners and in the market place: “Why should the Devil have all the best tunes?”

The temperance playlist was as narrowly focused as it was long, befitting its objectives of landing the heaviest punch; creating the biggest splash. Musically, ban-the-bottle songs might have left something to be desired; but the lyrics were magic. Could any modern singer-songwriter smuggle the word “government” into a chorus – or sustain pathos long enough to match Thomas Hood, Stanley Holloway, or the Nellie of “Hang on the bell, Nellie”?

Friends of Temperance, welcome here!

Cheerful are our hearts to-day.

We have met that we may hear

How our cause speeds on its way.

Here we pledge ourselves anew

Not to touch the drunkard’s drink;

Proving faithful, proving true,

We will from no duty shrink.

More imaginatively, a number of temperance choruses were explicit on the subject of decline and fall:

Gin-sellers are plying their ruinous trade;

Drunkards are dying and beggars are made...

or

Who hath woe and bitter sighing?

Who in anguish deep do groan?

Who in hopeless grief are crying?

Who in dire distress do moan?”

Saying “No!” was so important to abstainers that the very word often appeared in song:

When asked to quaff the drunkard’s drink:

We’ll promptly answer “No!”

Too oft it leads to ruin’s brink,

Victims who never stop and think…

or

Have courage my boy!

Have courage my boy!

Have courage my boy to say “No!”

Pinpointing drink as “foe”, “enemy” or “tyrant” was a wonderful exercise in anthropomorphism:

There’s a demon in the glass:

Dash it down! Dash it down!

or

Long the tyrant foe hath taken

Cherished loved ones for his own.

Now his cruel pow’r is shaken …

Soon will fall his tott’ring throne.

Alcohol was even called “king” and – less majestically – “robber”. After the battle, the temperance movement had to win new converts:

Let young and old, rich and poor, their energies unite:

Till all people, climes and tongues, in abstinence delight.

or

The hope of our country, the hope of our land:

The Armies of Temperance undaunted do stand.

Other choruses introduced the notion of an explicitly political crusade:

Write it in the nation’s laws: throwing in a licence clause;

Write it on each ballot white: so it can be read aright.

or

Public houses must be closed:

Abstaining is the plan proposed.

or

Rally for the right, boys! Rally once again!

Shouting loud for prohibition:

From each mountain, from each plain.

Not that prohibition was on Britain’s agenda: such a drastic solution to drunkenness, alcohol-dependence and impoverishment never really caught on this side of the Atlantic.

So why did temperance decline so dramatically after the Second World War through to this century? Wartime itself was partly responsible – with some public houses requisitioned and breweries converted into munition stores or factories. For the first time, public houses became subject to strict licences; enforced drink-up deadlines; demarcation of areas forbidden to children; minors unable to buy beer in open jugs or unsealed bottles.

Next, religion went into sharp decline. Thus temperance societies meeting in church, recruiting in Sunday schools, were losers too. And radio, TV, film, games consoles, Butlins; whatever, provided alternative entertainment, superior to a temperance convention.

Additionally, just as consuming wine and spirits became socially acceptable, expected, in the middle and upper classes, visible drunkenness was removed from the streets’ specific by-laws. Pedestrians and motorists – motorists not permitted more than a couple of alcohol units before driving home – ceased to witness hideous inebriation, drink-fuelled affray, routine rowdyism, less in football stadia newly equipped with closed-circuit TV.

Alcohol in the new millennium is still a problem: undoubtedly a disrupter of many a family setup; many a drinker’s health, welfare and security; many a child’s introduction into the world and later diminished schooling. Strong drink still leads to absenteeism from work, dismissal and long term unemployment. But such dependency now has rivals – recreational drugs, spice, off-course gambling, smartphones, vaping, cosmetics.

Many of those early temperance and friendly societies may stagger on – perhaps, like Hope UK, after a remake. And their cause has latterly received a boost from that most unlikely demographic – young adults. It’s become trendy for some skinheads and full-time students; some ladettes, apprentices and internees to concentrate more on hip hop, gym fitness, jogging, vegetarianism, environmentalism or travel, for example, as an alternative to booze. None these predilections nor an ever-present fascination with sex makes our 15- to 27-year-olds teetotalers overnight. But at least, via Facebook or Twitter, they can boast a Sober October or a Dry January, 30 lengths in the Lido, £50 for Yemen; the lecturing of recalcitrant parents – and not the other way round.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies