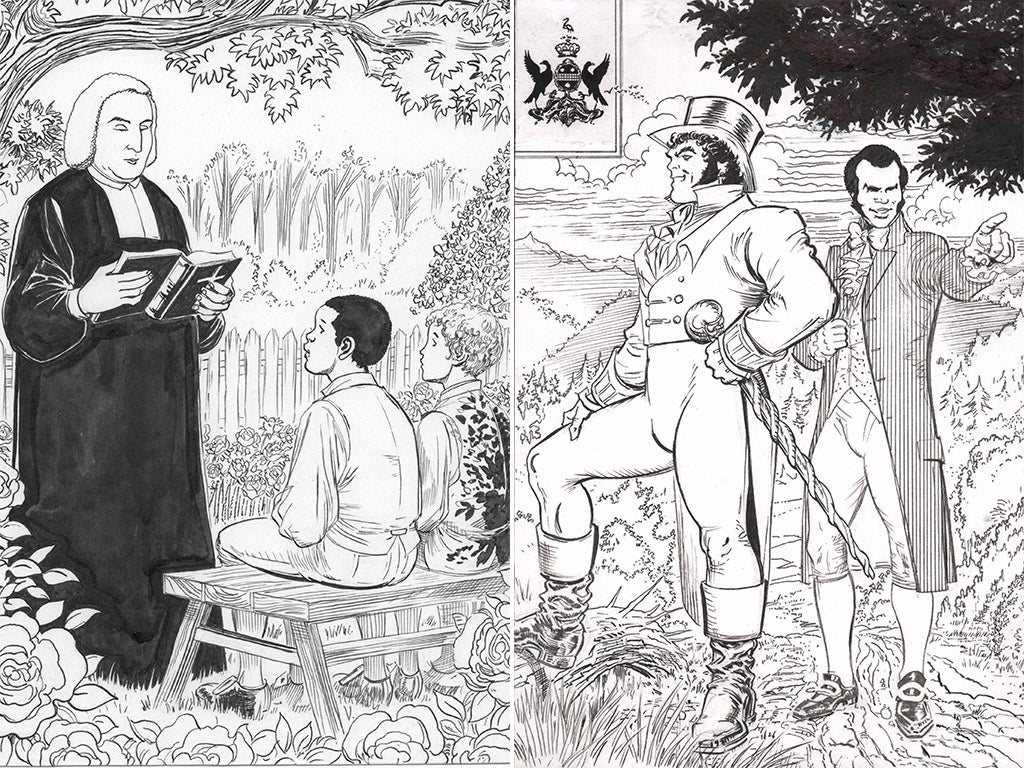

Bill Richmond: The black boxer wowed the court of George IV and taught Lord Byron to spar

Born into slavery in the USA, Bill Richmond went on to be the world's first black sporting superstar – and forged friendships with the English upper classes. Why is his name so little known, asks Luke G Williams, author of a new biography

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is 19 July 1821. King George IV has just been crowned and a lavish banquet in his honour is about to begin in Westminster Hall. Amid the extravagance and excess stand 18 powerfully built figures, whose imposing presence causes many of the nobles and dignitaries present to gasp in wonder and appreciation. Clad in retro-Tudor-Stuart costumes, these men are England's leading boxers and, as such, are the most famous and feted sportsmen in the land.

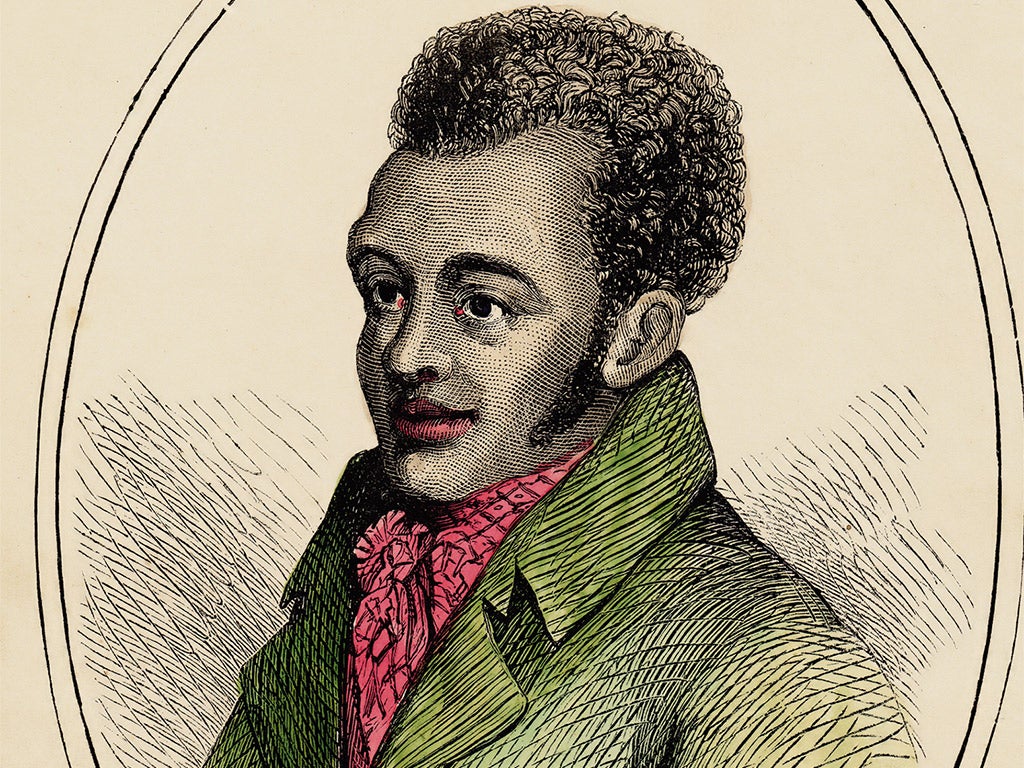

Among this somewhat incongruous group, one man stands out. Amid a sea of otherwise uniformly white faces, Bill Richmond is the only black man present. Richmond was no more than 5ft 9in tall and was already 57 years old, but in contrast to the corpulent, sweating king (who was just one year his senior), Richmond was still in magnificent physical condition, without an ounce of fat on his defined and wirily muscular frame, which had once been described by an admirer as a "study for a sculpture".

It had been 17 years since Richmond had first ventured into the glamorous but dangerous world of the London prize ring and he was now retired, but his achievements as a bare-knuckle boxer, or "pugilist", to borrow the Georgian term of choice, were impeccable.

Metaphorically and literally, Richmond had undergone a remarkable journey since his birth in 1763, having travelled 3,500 miles to escape life as a slave in a Staten Island parsonage in America to carve out a life of freedom, glamour and social acceptance in London. Through the considerable force of his personality and his unerring eye for social advancement, Richmond had – like a real-life Charles Dickens protagonist – hauled himself from a life of grinding and condescending servitude to sample the rarefied heights of elevated upper-class English society, having mixed with MPs, nobles and the likes of Lord Byron to become one of the most prominent "men of colour" of the Georgian era.

For a black man to achieve any level of prominence, let alone "celebrity", during the early 19th century was a rare feat. This was still a society, after all, where it was possible for the Encyclopaedia Britannica, in 1810, to describe "negroes" as "an awful example of the corruption of man left to himself".

Therefore it strikes me as a staggering collective omission by sports and social historians that the story of Bill Richmond has scarcely been told – as well as a shocking failure of imagination, given that the unlikely narrative of his life is worthy of a Hollywood movie.

Richmond was a pioneering black boxer – the trailblazer for the likes of Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali. He began life as a slave in America in 1763, arguably the worst social circumstances a man or woman could be born into. By the time he was a teenager, though, Richmond had won his freedom and entered the protection of the British soldier and noble Hugh Percy, his wit and intelligence having dazzled Percy while he was stationed in the loyalist stronghold of Staten Island during the American War of Independence.

In 1777, Percy persuaded Richmond's slave-owner, the Rev Richard Charlton, to release him into his care. This transformed the young man's life, and by the 1820s Richmond had become hugely respected, not only as a boxer but also as a trainer and tutor of both professional and amateur pugilists. For example, he gave lessons to the brilliant essayist William Hazlitt, who admiringly referred to him as "my old master", while Lord Byron was also said to have been one of Richmond's eager pupils.

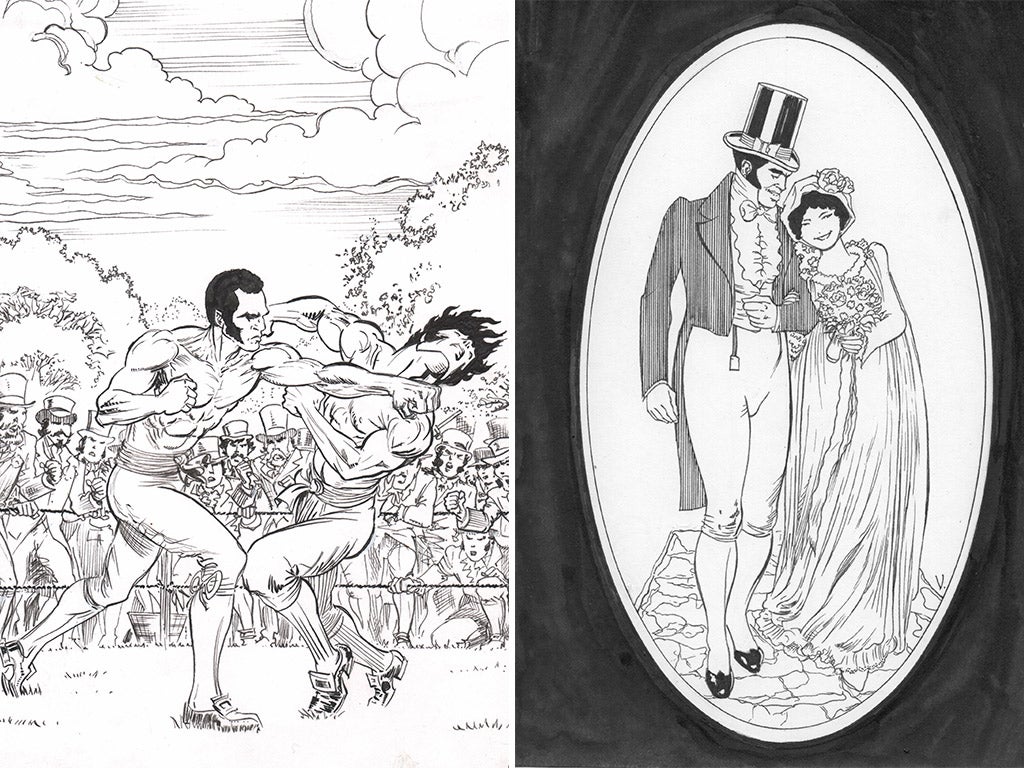

Percy brought Richmond to the North of England, paying for his tuition in reading and writing and then setting him up with a cabinet-making apprenticeship, an unusually high level of formal education for a black man living in Britain at this time. He later moved to London with his white wife, Mary, whom Richmond had met during his days as a cabinet maker in Yorkshire. It was in the capital that Richmond's life turned towards his unlikely fame; he was in his forties and with a young family to support when he became a successful boxer.

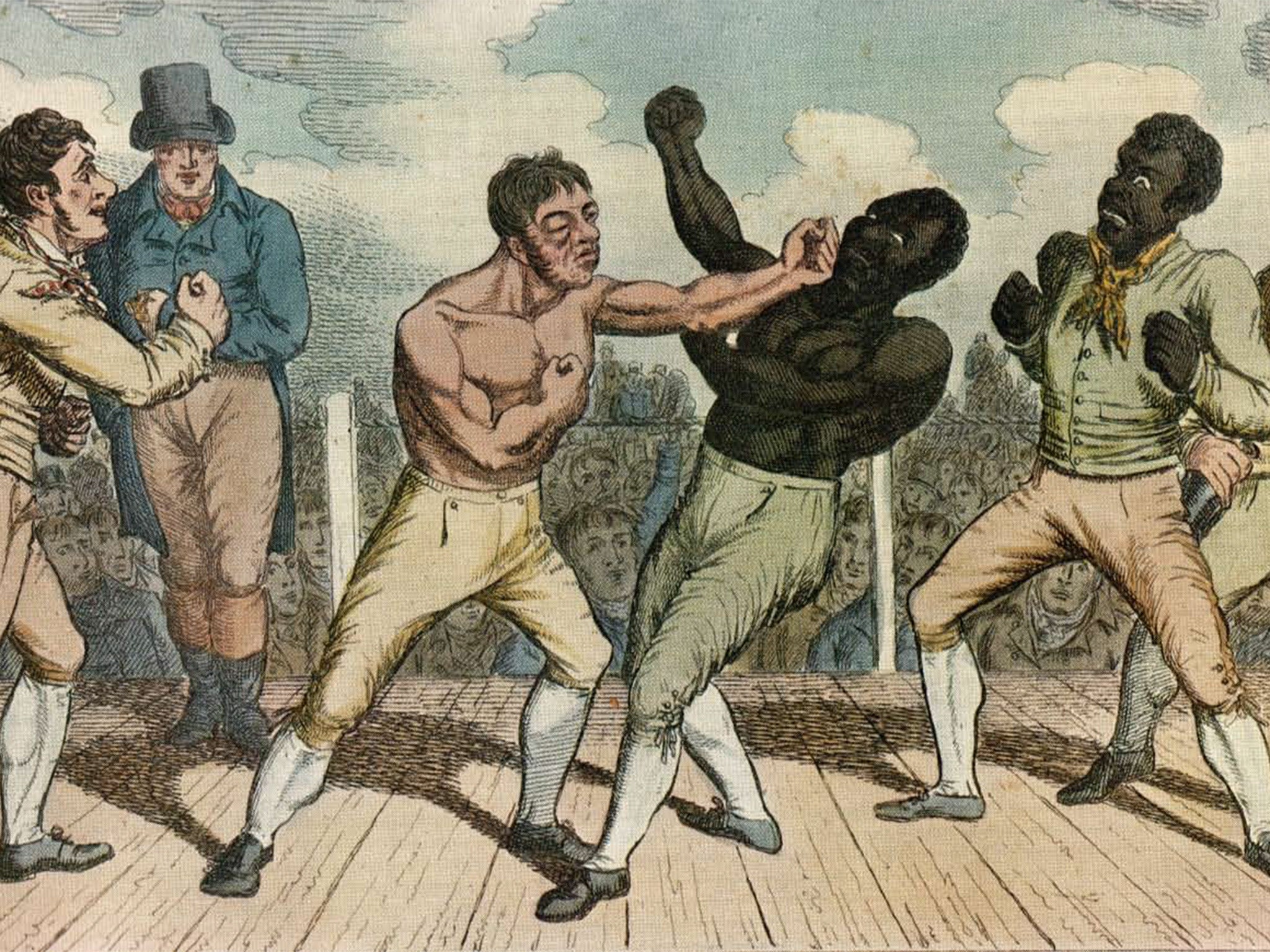

In the early 19th century, boxing, along with horse racing, was the dominant sport in England, with the pages of newspapers often containing exhaustive reports of the latest contests. Richmond soon became one of the sport's most famous practitioners, beating many top contenders and assembling a career record of 19 fights and 17 wins. His presence at the aforementioned coronation celebrations of George IV was the ultimate symbol of his acceptance into English society and sporting circles.

I had been aware of the bare facts of Richmond's life and career for a while, thanks to the George MacDonald Fraser novel Black Ajax – in which he appears as a subsidiary character – as well as the Channel 4 documentary Bare Knuckle Boxer and various books about boxing history – but I was shocked to learn that there had not been a single biography devoted to Richmond since his death in 1829.

Despite my fascination with Richmond's life, I initially had no intention of researching and writing his biography. However, all that changed in the summer of 2003, when I discovered a revealing and inspiring article from Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle in the British Newspaper Library in Colindale, London.

The article was a "funeral oration" written about Richmond after his death in December 1829 by Tom Cribb, the former holder of the English Boxing Championship. It contradicted the narrative I had read in boxing and sports history books: that Richmond and Cribb had been irredeemably bitter enemies. Certainly the men, at one stage, shared a fierce rivalry – Cribb had, after all, defeated Richmond in the ring in 1805, before also vanquishing his protégé, Tom Molineaux, in a pair of controversial championship contests in 1810 and 1811. Nevertheless, Cribb's warm and generous tribute to the deceased Richmond, modelled on Mark Antony's tribute to Julius Caesar in Shakespeare's play, suggested that once the men had retired from the prize ring, they had become close friends.

Reading the speech, I also found myself profoundly moved. Partly, I think, this is because it was written by "plain, blunt Tom Cribb", one of the toughest, most manly men who ever walked the face of the earth, yet when he wrote about Richmond, Cribb seemed uninhibited, unabashed and unashamed in expressing affection and love for his friend. "You all lov'd Richmond once," he emphasised at one point, a sentiment that could seem like a trite rhetorical flourish but, coming from Cribb, who also admitted that his "heart is slumbering in that shell with Billy", it was a line that, for me, achieved significant emotional resonance.

Cribb's speech was also fascinating in terms of how it addressed Richmond's ethnicity. To modern eyes, its liberal use of the "N-word" and Cribb's reference to Richmond as "blacky" are, at worst, offensive and, at best, painfully naive and clumsy. However, despite its embarrassing stumbles ("I am not here to say that Bill was white"), Cribb's speech succeeded in doing something quite remarkable: directly challenging the barriers and prejudices that were so prevalent in Georgian England.

When Cribb wrote his eulogy, the Abolition of Slavery in the British Empire was four years away, and the Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln still 33 years in the future. Yet, years in advance of these landmark events, Cribb was making a brave call for all human beings to be judged by their characters and actions, and not their ethnicity. Cribb's rejection of the idea that "colour always [makes] the man" was both honestly expressed and inspiring; in the face of death, as Cribb pointed out, all men, no matter what their "colour", will one day succumb to the same fate and "tumble" from their "perch".

The tribute helped to bring into focus for me just how remarkable a life Richmond had led. Through the course of the following decade of research, which took me from the dusty archives of Britain to the church in Staten Island where Richmond was once a slave, I discovered that on many occasions Richmond suffered abuse because of his ethnicity. Whether in the boxing ring, while walking the streets or while tending the bar of the Horse and Dolphin – the public house which became a focal point for London's black community after Richmond's fight earnings enabled him to become landlord between 1810 and 1812 – the threat of racial taunts and violence was ever-present for Bill.

In an approving piece in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, he was referred to as "the Lily-white", a popular Georgian term for chimney sweep. This was typical of the sort of patronising language that even Richmond's admirers used to describe him. He was also referred to variously as "the black", "Mungo", the founder of the "sable school of pugilism" and the "black devil".

The bravery he demonstrated to overcome these taunts and prejudices and live a professional and public life was considerable. Furthermore, Richmond's pugilistic exploits caught the imagination of the public and were regularly recounted in detail in the pages of national and local newspapers, and this at a time when most newspapers ran to only four pages in length.

The extent of Richmond's considerable fame can also be measured by the fact that artists of the period produced prints of him, such as Robert Dighton's A Striking View of Richmond. Furthermore, the coronation celebration of George IV was not his only encounter with royalty, for when Frederick William III of Prussia visited London in 1814, Richmond was one of the "celebrated professors of the fist" who were commissioned to spar in front of him and other assorted royals and nobility.

Another of Richmond's notable characteristics was that he was as far removed from the common stereotype of the monosyllabic thug as it was possible to be. Those who met him frequently referred to his excellent manners, witty conversation and intelligence, as well as his ability to tell amusing "milling anecdotes" – a series of qualities that put paid to the bigoted but widespread perception at the time that black people were intellectually inferior to whites. Indeed, Richmond was invariably better educated than his white contemporaries, several of whom were illiterate.

Pierce Egan, the writer who was a key factor in popularising the exploits of Georgian boxers, wrote at length about Richmond's intellect in the first volume of his journal, Boxiana, declaring: "He is intelligent, communicative, and well-behaved; and however actively engaged in promulgating the principles of milling, he is not so completely absorbed with fighting as to be incapable of discoursing on any other subject."

Impressively, Richmond was also a man of iron self-control; in retirement, unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not become corpulent and dissolute, but retained his trim, muscular features, and remained largely abstemious in his approach to alcohol, with The Morning Post observing that he seldom took "more than a glass of sherry and water".

Richmond was also endowed with the business sense and altruistic spirit of a social entrepreneur. For young black men in London during the early 19th century, boxing was one of the few routes (albeit a dangerous one) to paid and independent employment, and Richmond would often tutor such men; one of his pupils was another former slave, Tom Molineaux, whom Richmond mentored and trained for his famous championship contests against Cribb in 1810 and 1811.

These were arguably the two most significant sporting occasions of Georgian times, attracting huge crowds and unprecedented press attention, and Richmond was a key figure in brokering and promoting both bouts. Sadly, while Richmond bucked the age-old cliché of the fast-living sports star, Molineaux's career and life were marred by personal excesses and proved all too short-lived.

Richmond has a good case to be recognised as the first black sportsman of national fame and international significance, the trailblazer to a long, illustrious and socially significant line that eventually stretched to include the likes of Jack Johnson, Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson and Muhammad Ali. Richmond wouldn't have known this in 1821, of course, but as he stood at the heart of coronation festivities – a black man thriving within a bastion of white privilege – he could have been forgiven for pausing to reflect just how far he had travelled, and how remarkable a life and career he had already led.

Given the wide scope of his accomplishments, it is high time that Richmond was afforded the prominent place in British history that his life and achievements so richly deserve. I hope that my book Richmond Unchained will enable more people to learn about this remarkable man and his remarkable life, and that the unveiling yesterday of a memorial to Richmond at the Tom Cribb pub in Panton Street, London – once the stomping ground of his rival-turned-friend, as well as the location where Richmond spent the last evening before his death – will provide a lasting tribute to a man who overcame the terrible circumstances of his birth to become one of the wonders of the Georgian age.

'Richmond Unchained' by Luke G Williams (Amberley, £15.99) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments