Battle of Waterloo: Was it just an unpopular adventure led by an establishment hate figure?

The Iron Duke's war against the poor contributed to both the Peterloo massacre and, ultimately, his own undoing, says Colin Brown

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Battle of Waterloo will be celebrated with a national memorial service at St Paul's Cathedral to mark its bicentenary on Thursday – and while descendants of those who fought there will be among the VIP guests, they have been warned that it will not be "triumphalist". Nonetheless, it has to be said, the Duke of Wellington's victory over Napoleon and the Bonapartists at a little ridge near the hamlet of Mont St Jean, 11 miles south of Brussels, was so complete that "Waterloo" has become synonymous with a crushing defeat.

But, it must also be added, that is not how it looked in the spring of 1815. Radical MPs such as Sam Whitbread, son of the brewer, were appalled at the prospect of Britain being dragged into another costly war against Napoleon. The Commons were just as divided as during the debates before the Iraq war in 2003. Whitbread and other Radical MPs accused Wellington of going to war for regime change – just as the anti-war MPs accused Tony Blair over Saddam Hussein.

In a parliamentary exchange from 28 April, Whitbread said: "For the first time in the history of the world, war is being proclaimed against one man for the demolition of his power. [But] what is his power? His people: and the conclusion therefore is inevitable, that hostilities are to be renewed for the desperate and bloody enterprise of destroying a whole nation."

Britons had been enjoying the months of peace that followed Napoleon's abdication in 1814. For the first time in years, they were able to travel to the Continent without the fear of being locked up as spies. And among such tourists was the Radical MP Thomas Creevey, who went with his ailing wife to Brussels to enjoy the Continental air, the boulevards and balls, and walks in the central park. In early April, like characters in the Thackeray novel Vanity Fair , they were overcome by the preparations for a war nobody wanted.

Creevey received a letter from a fellow Radical MP, Henry Grey Bennet, bringing him up to date with the latest Westminster gossip: "Prinny [the Prince Regent] of course is for war. As for the Cabinet, Liverpool [the Prime Minister] and Lord Sidmouth [Home Secretary] are for peace; they say the Chancellor is not so violent the other way. But Bathurst [Secretary of State for War] and Castlereagh [Foreign Secretary] are red hot…"

Even Wellington's brother Richard Wellesley, a former Cabinet minister, shared the view of the anti-war faction at Westminster. He warned his brother, and the Prime Minister – though he never made it public – that the idea Bonaparte did not have public support in France was a "fallacy". But there was another reason why Wellesley thought a fresh war was a bad idea: Britain was broke. Fighting wars against the French for the best part of a generation had come at a crippling cost. Pitt had introduced income tax as a novel way of paying for the war, but debt had mounted. By 1816, it had soared to 230 per cent of GDP (compared to around 80 per cent today).

At home, there was commotion in the streets. The Regency period – the so-called Age of Elegance – was also the era of riots. There were riots against the industrialisation that was forcing people from the farms to the factories; there were protests for Parliamentary seats for the new industrialised towns in the Midlands and the north of England; and there were bread riots. In March 1815, soldiers were called out to protect MPs in the Commons from a mob protesting against a bill – the so-called Corn Law – which put up the price of bread for the poor to protect the profits of the rich from cheap imports flooding in as a result of the peace. The farmers who gained from this naked piece of protectionism included the landed gentry, the same small elite who held seats in the House of Lords, controlled seats in the Commons – "pocket boroughs" – and ran the country before most people got the vote.

Three months before the battle of Waterloo, on 12 March, 1815, Lady Melbourne, sitting in her mini-palace, Melbourne House (now Dover House, the Scotland Office) on Horseguards Parade, Whitehall, wrote to her niece Annabella, Lady Byron, about the mob outside her windows: "It was necessary to have ye assistance of the Military and about a dozen of the Horse Guards galloped at the people and dispersed them..."

Lady Melbourne, one of the fading beauties of Georgian society, added: "Today it rains hard which will probably prevent their assembling in great Numbers and the Town is full of Military so I conclude the Ministers think themselves tolerably safe – they were very much frightened and not without reason for this Mob seems to be extremely savage and much more in earnest than I ever remember… A loaf of Bread, Steeped in Blood and tied up in black Crape was thrown into Carlton House Garden [home of the Prince Regent]…"

She was hinting at the fears stalking Liverpool, Wellington and the ruling class: that Britain was facing a revolution, such as the one triggered in France 25 years before, by women seeking relief from hunger by marching on Versailles for bread. Seeing soldiers on the streets around the Palace of Westminster, some Radical MPs protested they were being subjected to martial law.

Their protests – over this, the Corn Laws and indeed the forthcoming campaign against Napoleon – went unheeded. In Brussels, Creevey met the Duke of Wellington strolling in the park and asked him whether he and the Prussians under Blucher could beat Bonaparte, later recording their conversation in his journal: "He stopt and said in the most natural manner – 'By God! I think Blucher and myself can do the thing'... Then, seeing a private soldier of one of our infantry regiments enter the park, gaping about at the statues and images – 'There,' he said, pointing at the soldier, 'it all depends upon that article whether we do the business or not. Give me enough of it, and I am sure'."

That "article", the anonymous figure in a red coat, was the common soldier, who Wellington had angrily called "the scum of the Earth" in an 1813 letter to Lord Bathurst, when his men went on the rampage after routing the French in northern Spain. Wellington's defenders claim he was merely speaking in anger but I think it went further than that: the aloof, snobbish, patrician Duke really believed in the natural order of things: the rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate. And while he was proved right about the battle – though he told Creevey the day after that it was "the nearest run thing" – his contempt for his "articles" would one day undo him.

Wellington's "common" soldiers returned to Britain to find a country in disorder, almost at war with itself; and as I discovered while researching my new book on the Waterloo "scum", many of them would be its casualties. It turned out that nearly all the men hailed at the time as heroes would end their lives forgotten and in poverty. Men such as Corporal Francis Stiles, who claimed he captured the Eagle and colours of the French 105th Regiment and died in obscurity in Clerkenwell. Or Irishman James Graham of the Coldstream Guards, who was hailed as "the bravest man in Britain" for helping to close the north gate at Hougoumont farm – a turning point in the battle – and rescuing his brother from the burning barn. (Graham wrote to the Chelsea Hospital Commissioners when he was 50, applying for an increase to the 9d – or roughly £2.50 in today's money – that he received as a daily pension.)

In part, they were the victim of global forces. As economic depression spread across most of Europe after Napoleon's defeat, Britain suffered a farming slump, caused by a surge in cheap imports. Meanwhile, domestic crop failures – blamed on the eruption of the Tambora volcano, which spewed dust into the atmosphere and blotted out the sun – meant that wheat yields fell by 31 per cent, and incomes plummeted. And there was worse. Demand for cloth fell, as soldiers and sailors discharged from the Army and the Royal Navy joined thousands of unemployed cotton workers – displaced by the new looms, which could do the work of 700 men – all looking in vain for work.

Weavers who once earned 15 shillings saw their wages cut to five. And many families – including Jeremy Paxman's ancestor Thomas Paxman – split up as they were shipped by canal to northern towns, such as Bradford, to work in the textile mills.

Distress led to rioting in normally sleepy rural towns such as Ely. But Parliament then increased the pressure on the poor by abolishing income tax on the wealthy and prescribing austerity for the rest. After the defence budget was slashed by 75 per cent and the Army cut from 233,000 to 92,000, thousands of former "Waterloo Men" were forced to get poor relief or beg for a living. One Rifleman Harris saw "thousands of [ex-]soldiers lining the streets and lounging about the different public houses with every description of wound and casualty incident on modern warfare".

Presiding over it all was the bloated Prince Regent, who was as much reviled as the newly-restored Bourbon monarchy in France. In the same year as Waterloo, "Prinny" commissioned John Nash to turn his beach house in Brighton into a fantasy Moghul palace – the Royal Pavilion – and refurbish Carlton House at vast expense. The Government was so alarmed that Lord Liverpool, Lord Castlereagh and the Chancellor Nicholas Vansittart wrote to the spendthrift prince, warning him to rein in his spending as the only means of "weathering the impending storm…"

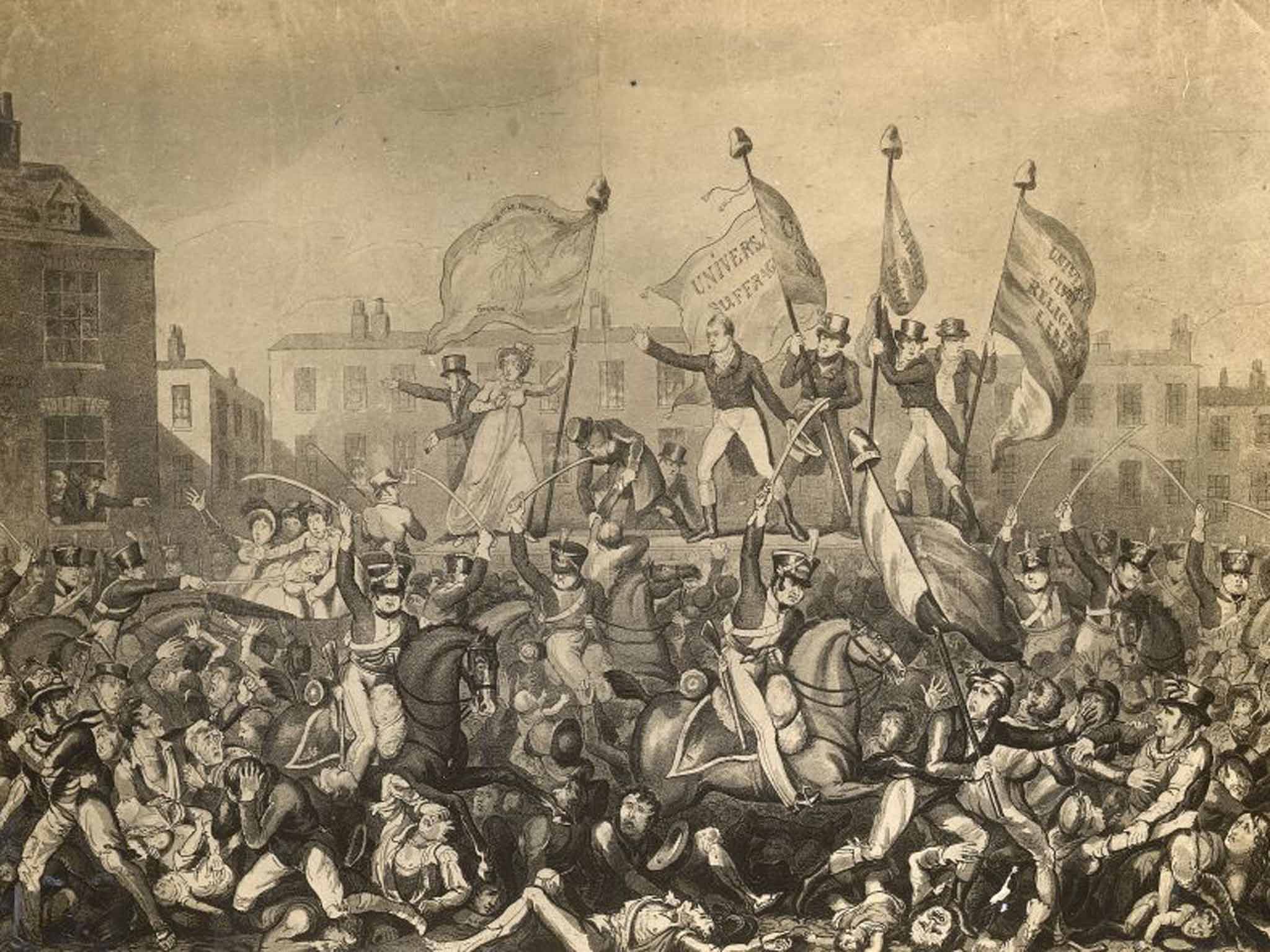

The storm they feared broke in Manchester on 16 August 1819 when an estimated 60,000 men, women and children crowded onto St Peter's Field (now the site of the Radisson Hotel) to hear a powerful public speaker Henry "Orator" Hunt – the Tony Benn of his day – call for representation in Parliament for the burgeoning industrialised towns of the Midlands and the North, who had no MPs in the Commons to speak up for their people. And among the crowd was one Waterloo Man – John Lees – whose story can stand for many.

Lees had enlisted in 1812, aged 14, as a Royal Artillery Driver after giving up a job as a cotton spinner in his father's mill in Oldham, Lancashire. (Exactly why he gave up work in his father's mill to enlist is unclear but, like many "scum of the earth", you had to be running from something – a pregnant girlfriend, a jail sentence, poverty – to join the Army.) He was posted to Major Robert Bull's Royal Horse Artillery 1 Troop, and on the muster roll was described as 5ft 4in tall, with a "fresh" complexion, grey eyes and brown hair.

Bull's troop were equipped with five-and-a-half-inch Howitzers and John Lees drove the cart full of powder and shells to supply the gunners on the battlefield at Waterloo in the thick of the fighting. Some time after returning to Britain, he was discharged from the army, and returned to Oldham for Christmas in 1818. His father Robert gave him back a job at his mill, but on 16 August 1819, John defied his father by walking to Manchester to hear Henry Hunt.

The masters of the mills like Robert Lees saw Hunt as the enemy, and there had been a long history of social unrest in Oldham, a Radical town. In the eyes of the mill owners, the crowds converging on Manchester were dangerous associates of the frame breakers, the followers of "Ned Ludd" who had tried to wreck their businesses by burning down their mills. Among the poor, however, there was a carnival atmosphere, with bands playing, banners waving and marchers singing as they entered the square in Manchester.

The local magistrates, overlooking the ground from the windows of a nearby house, panicked when they saw the size of the crowd, read the Riot Act and ordered Hunt to be arrested by special constables. Militia on horseback – including local publicans, some of whom were drunk – backed by the 15th Dragoons, who had fought at Waterloo, drew their sabres. In the ensuing mêlée, 650 were injured in 20 minutes and at least 15 were killed; 187 men and 31 women were slashed by swords, and at least as many trampled or beaten by the horsemen or special constables.

They caught John Lees as he cowered under the speaker's platform. He was "sabred" and slashed across the right elbow down to the bone when he tried to protect himself from their blows. Then he was battered by the special constables with their truncheons. Three weeks later, he died from his injuries. The inquest heard his back was black and blue, and "much blood gushed from the mouth and nostrils" when his body was moved. Towards the end of the shameful day which did for him, a volunteer constable was heard gloating to the crowd: "This is Waterloo for you." Within a week, the Radical Manchester Observer ran the headline 'The Peter Loo Massacre'.

The Government should have opted for reform. Instead, they chose repression, introducing the "Six Acts" to clamp down on freedom of speech. And Wellington's worst fears were realised a year later, when the "Cato Street conspiracy" was uncovered. A revolutionary firebrand, Arthur Thistlewood, plotted to assassinate the Cabinet at dinner, Wellington among them – at a private house in Grosvenor Square, but his gang included a Government spy and they were arrested. On 1 May 1820, the ring-leaders were publicly hanged and then beheaded outside Newgate prison for treason.

The Duke used his authority as the man who had vanquished Napoleon to resist change, but over the next decade, the violence increased. Bristol was set on fire and occupied by rioters for three days after the Lords rejected the Reform Bill in 1831. Mobs smashed the windows of the Duke's London residence, Apsley House, while his wife Kitty was on her deathbed. Wellington resorted to metal shutters, and was ridiculed as the "Iron Duke".

In 1828, when Wellington became Prime Minister, he rode to Downing Street on his war horse, Copenhagen, to show the smack of firm government. After his first Cabinet, he complained: "I gave them their orders and they wanted to stay and discuss them!" The ultimate military man, the Iron Duke saw politics as a battle and stood implacably against reform. But he was forced to resign when the tide of change became unstoppable – and in the end, the 1832 Reform Act was Wellington's Waterloo.

Colin Brown is the author of 'The Scum of the Earth – What Happened to the Real British Heroes of Waterloo?' (The History Press, £20)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments