Suicide rate of young men falls to 30-year low

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

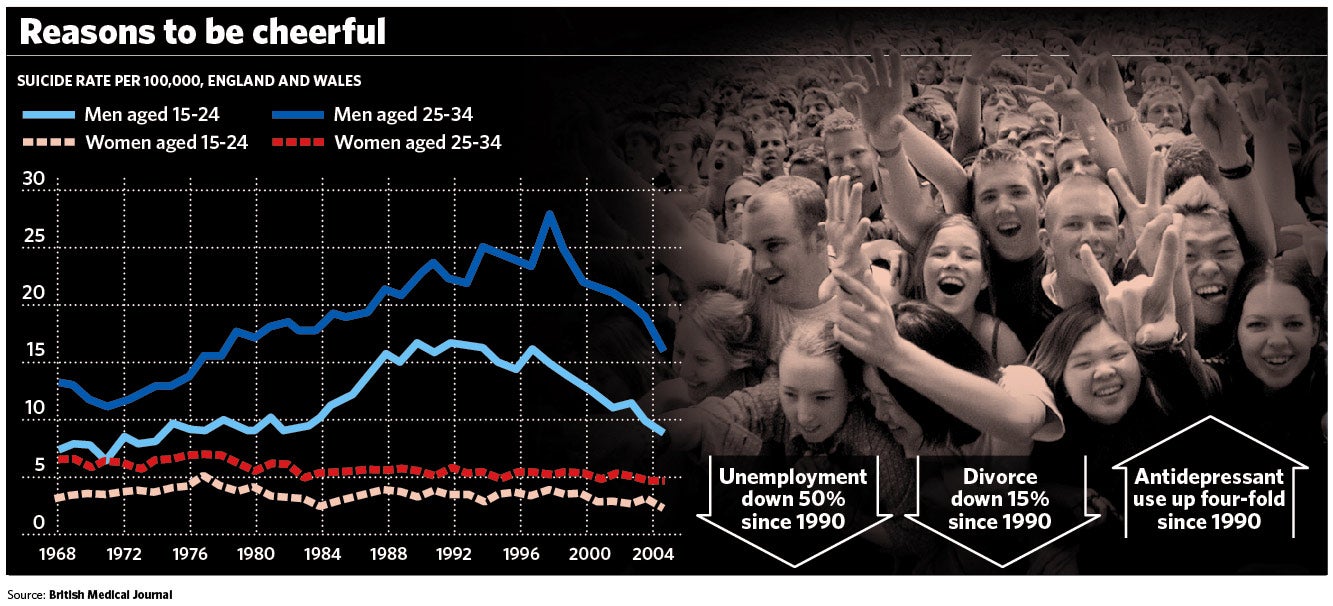

Your support makes all the difference.Suicide rates in young men have fallen to their lowest level since the 1970s, marking the end of a three-decade long rise.

In young women, suicide rates have been in steady decline for the past 40 years and are now at their lowest level since 1968.

The overall downward trajectory stands in defiance of claims that young people are suffering intolerable levels of stress from the pressures of modern life.

It suggests that those aged 15 to 34 are either happier than previous generations, or better equipped to withstand the pressures – despite increasing drink and drug use, rising obesity, higher levels of sexually transmitted disease and a more competitive, acquisitive and celebrity-obsessed culture. Or it may be they have found it harder to kill themselves, because new measures have put some suicide methods beyond reach.

During the 1980s, Britain experienced an "epidemic" rise of suicide in young men, coinciding with a huge increase in unemployment under the government of Margaret Thatcher. Male school leavers who found themselves jobless faced a bleak future which pushed some to the wall.

At the same time, rising divorce rates took a heavy toll on some men who found themselves homeless after splitting from partners. During the 1990s, suicide rates in males aged 15 to 24 reached an all-time high and the rate among those aged 25 to 34 reached its highest level since the 1920s.

All industrial nations experienced a similar rise in suicides among young men over the same period, which still remains at least partly unexplained. Although young women were more likely to attempt suicide, usually by overdosing on pills, men were more likely to succeed.

A new analysis of the figures, by scientists at the University of Bristol, shows the trend was rightly called an "epidemic" because, by the 1990s, suicide accounted for a fifth of all deaths in young men – and men aged 25 to 34 had the highest suicide rate of all age groups in both sexes. "Such trends have led to suicide becoming a major contributor to premature mortality and are thought to indicate deteriorating mental health in younger people," the authors say in the British Medical Journal.

Since the 1990s, the rates have come down dramatically – by half among 15- to 34-year-olds, from a rate of 16.6 per 100,000 in 1990 to 8.5 per 100,000 in 2005. Among men aged 25 to 34, the rate declined from 22.2 per 100,000 to 15.7 over the same period. Removing access to a method is one of the most effective ways of reducing suicide because the act is often impulsive. The introduction of catalytic converters, which were made mandatory for new vehicles in 1992, has almost eliminated one of the most popular suicide methods. Motor gas deaths, in which a hose is run from the exhaust into the car, fell from 508 in 1979 to 219 in 2005.

Other measures that have helped cut the rate include reducing pack sizes of paractamol for sale in supermarkets to a maximum of 16, which has reduced deliberate overdoses, and the deployment of volunteer patrols and safety gear such as nets and barriers at suicide hot spots such as the Clifton suspension bridge in Bristol and Beachy Head, Sussex.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments