Cancer survival rates hampered by shortage of NHS pathologists

Time-lag in training specialists to meet growing demand means that diagnoses and life-saving treatment are dangerously delayed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Government promises to improve cancer survival rates and reduce hospital superbugs are under threat because of a lack of pathologists, medical experts claimed yesterday. Seriously ill patients are missing out on life-saving treatments because of a shortage of highly trained specialists in some areas, according to the Royal College of Pathologists (RCoP).

Pathology is vital to the NHS: more than 70 per cent of all diagnoses are dependent on pathology tests. The equivalent of 14 different lab tests – biopsies, cervical smears, blood tests and the like – were carried out for every person in the UK last year.

But only 4 per cent of the NHS budget is spent on pathology services. And the number of senior pathologists needed to carry out these tests is not keeping pace with demand. Experts warn patient safety is being put at risk because NHS trusts struggling to cut costs are ignoring recommendations that consultant pathologists should not work alone.

Despite recent increases in training posts by the Department of Health, the expected number of newly qualified consultant pathologists seems unlikely to meet demand. Training can take up to 15 years, and large numbers of pathologists are taking early retirement.

Cutting-edge treatments for anything from cancer and haemophilia to transplants must be strictly supervised by specialists including immunologists, clinical chemistry pathologists and haematologists. But according to the RCoP, their specialist skills are often overlooked because they work behind the scenes.

Tim Stephenson, director of workforce planning at the RCoP, said: "Our analysis shows the expansion of consultant posts has stalled in most areas, largely down to financial constraints upon NHS trusts, but also because there are not enough pathologists. This has stopped patient services from developing at the pace they should have, which means promises made to the public about improvements in the quality of care cannot be delivered.

"People in some areas will get specialist services but in other areas people will not get care at the level they need when they need it most. This will lead to delays or poor decisions being made about treatment which could eventually affect their survival. This is one reason why cancer survival rates are so poor in the UK. The situation is 100 per cent critical."

Complex medical advances such as stem-cell transplants for leukaemia patients mean a growing number of critically ill people need the expertise of haematologists. But there are 60 vacant posts across Britain and more than 15 per cent of consultants are due to retire in the next five years.

Archie Prentice, consultant haematologist at the Royal Free Hospital in London, said: "For some patients, care is not as good as it could be. We all try to compensate but eventually there will come a point where gaps appear, services begin to creak and it gets harder for patients to see a consultant with the right expertise."

Peter Wilson, consultant microbiologist at University College London, said: "It is difficult in some areas to get even one applicant for a vacant post. These places are in real trouble because this is slowing down progress in reducing hospital-acquired infections."

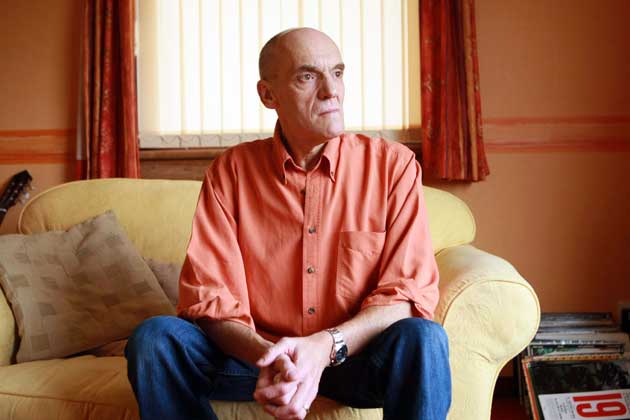

Allergies are on the increase but thousands of sufferers do not have access to the UK's 59 immunologists. David Stobbart, 59, from Inverness, was diagnosed with common variable immune deficiency after he was finally referred to an immunologist 19 years after he first became ill. "From the age of 30 I repeatedly went to see my GP with chest infections and I must have taken hundreds of antibiotics," he said. "The doctors didn't realise there was something wrong with my immune system until my lungs were permanently damaged."

The Department of Health said yesterday: "Workforce planning takes place in close consultation with all relevant stakeholders, including the RCoP, and we are seeking to address this issue. The department will continue to work closely with stakeholders to develop the medical workforce to meet the needs of the NHS."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments