Victorian diseases: Back from the dead

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

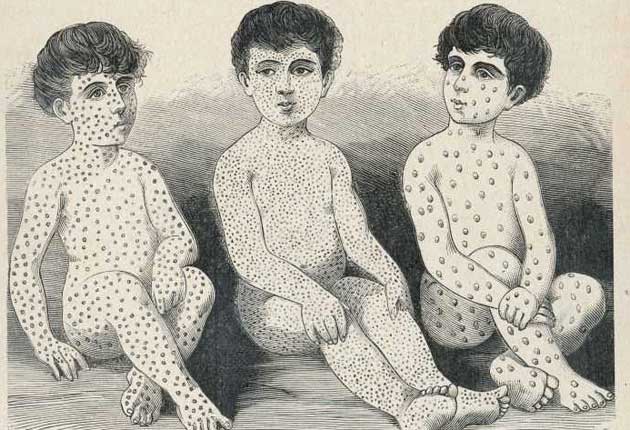

Your support makes all the difference.Charles Dickens knew more than he would have wished about scarlet fever. His son, Charley, was afflicted by it, causing the family to leave Paris hurriedly and return to London in 1847, and it featured in several of his novels. It was a much-feared disease that caused devastating epidemics through the 19th and early 20th centuries, resulting in thousands of deaths.

Now, 160 years later, it is making a comeback. Almost 3,000 cases were recorded in 2008, the highest total for a decade, and doctors fear a dangerous strain of the infection is becoming more widespread.

It is not the only 19th century disease to make a comeback. Mumps and measles are on the rise, whooping cough notifications are up and cases of typhoid are increasing. Justine Greening, shadow minister for London, last week claimed London was experiencing a surge in Victorian diseases more closely associated with the world of Dickens than the modern era of health clubs and fitness regimes.

Ms Greening, Tory MP for Putney, said there were 393 cases of mumps in the capital in 2008, up by 214 per cent in a year, whooping cough cases had quadrupled in five years to 252, there were 501 cases of scarlet fever (a rise of 153 per cent since 2005) and 127 cases of typhoid. She accused the Government of failing to invest enough in public health or to appoint enough school nurses.

"The rise of these highly infectious and potentially fatal diseases in our cities is truly alarming, the Government must do more to ensure the public health of Londoners," she said.

Is she right? Greening's charge is accurately targeted and hits Labour where it hurts most – on health. After a decade in which record sums have been spent on the NHS and living standards have risen, why should diseases associated with poverty and pestilence be on the rise?

First, a little context setting. In Dickens' day hundreds of thousands of people fell victim every year to measles, mumps, whooping cough and scarlet fever and thousands died. Epidemics were frequent and lethal on a scale undreamt of today. In the last century the toll from infectious diseases has declined dramatically, thanks to improved housing and sanitation, antibiotics and vaccination.

Take whooping cough. Latest figures show there were just over 1,500 notifications in 2008, the highest total since 1999. Yet as late as the 1950s, regular epidemics infected upwards of 150,000 people a year in England and Wales. Cases fell sharply following the introduction of whooping cough vaccine in 1960 to below 20,000, (peaking again in the late 1970s at 60,000 cases following a scare about the vaccine's safety).

Next, most infections are cyclical – with natural peaks and troughs. Scarlet fever follows a cycle rising and falling roughly every four years – and is currently on a rising trend. Flu is also cyclical, with some years worse than others, and we are still awaiting the century's first pandemic, after three global epidemics last century in which millions died.

Vaccination plays a key role in diseases such as measles. The decade-old scare over MMR, which saw vaccination rates slump from 92 per cent to below 80 per cent nationwide, and as low as 30 per cent in some areas, has seen cases surge.

There were 1,370 cases in 2008, up a third on the previous year and the highest total since records began in 1995. Scientists warned last summer that Britain faced the threat of epidemic on the scale of those that occurred in the 1950s and 1960s, before vaccination was introduced, with up to 100,000 people infected.

Ministers responded by launching a publicity campaign to persuade parents of unvaccinated children to bring them in for the jab and more than one million doses of vaccine were stockpiled by primary care trusts.

Mumps, also covered by MMR, is on the rise for different reasons. There were 998 cases in the first two months of 2009, compared with 322 in the whole of last year. This looks like a steep rise until set against the last peak, in 2005, when 43,000 cases were recorded.

The recent decline in MMR vaccination is not responsible in this case. The age group chiefly affected – university students aged in their late teens and early twenties – received the MMR vaccination around 20 years ago, long before the scare over its supposed link with autism led to a fall in uptake.

Some were too old to be vaccinated with MMR, which was introduced in 1988, and some had only one dose, which was inadequate to provide complete protection. In other cases, even two doses has proved insufficient, defined as examples of "vaccine failure". Increased numbers of people at university and college, living in close contact, makes it easier for the disease to pass from one person to another. Experts say cases of mumps are expected to rise over the next few years, until the fully vaccinated population reaches university age.

Typhoid is the odd one out in the list, because it is not infectious, and rarely transmitted in this country. It is passed from person to person via contaminated food and water and most cases are contracted abroad. The number of patients affected has risen to more than 500 a year, from 300 a decade ago.

Vaccination against typhoid is available to travellers but not routinely offered to UK residents because of the low risk. The recent rise in cases is likely to be linked with increased numbers of visitors to the UK from abroad.

So Ms Greening's account, of recent rises in infectious illnesses signalling a return to the Victorian era, is a colourful interpretation of the facts. Diseases, like politicians, come and go. Occasionally we can influence their passage, sometimes we can hold them back but often the best we can do is hope and pray.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments