Hydrocephalus: the lethal brain condition

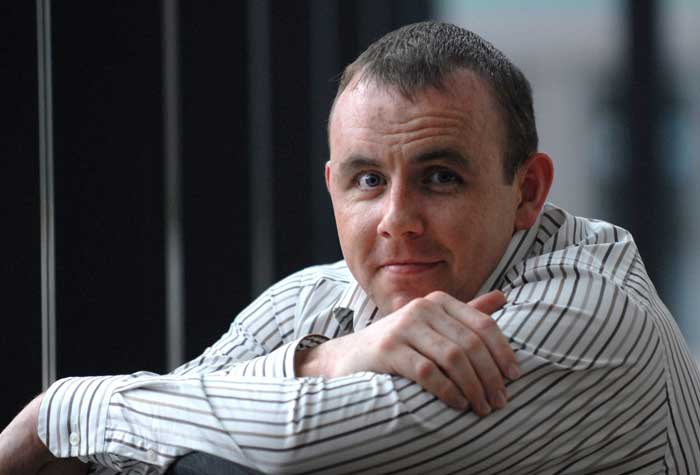

Crippled by blinding headaches, Simon Lannon has undergone surgery more than 30 times. But instead of throwing in the towel, he's stepping up to his greatest challenge yet – a supreme test of physical endurance

We've all woken up with a headache: perhaps a self-inflicted dull ache after a night on the tiles, or maybe a recurring, stress-induced migraine. Twenty-nine-year-old Liverpudlian Simon Lannon wakes up every single day with a headache, and they're not the sort that can be shaken off with a few ibuprofen and a hearty breakfast.

"I have OK days, medium days, and bad days," explains Lannon, who suffers from a brain condition called hydrocephalus, where spinal fluid accumulates on the brain instead of flowing around it, and had his first major operation at the age of six. Since then, he has undergone surgery more than 30 times. "On an OK day, the headache will subside within a couple of hours. On a medium day it will last until midday, or later. On those days I can still get up and get moving, but on a really bad day I can't do anything. I'm just flat out, doing nothing."

Hydrocephalus is not an uncommon condition, but Lannon has the additional complication of a Chiari malformation, which means that part of the back of his brain herniates down from the skull into the cervical spine and the fluid does not drain naturally. This has the potential to become life threatening, and is regulated by two shunts, both prone to blocking, and a titanium valve. Remarkably, Lannon, who works in Manchester as an architectural technician, recently finished a triathlon, using the event to raise money for the Walton Centre in Fazackerley, near Liverpool, the specialist brain unit where he receives treatment.

Spending a large chunk of each of his school years in hospital instead of playing football with his friends has made Lannon independent and determined. In fact, he is more interested in outdoing his peers than merely measuring up to them. This attitude led to his decision to go one better than the standard Olympic triathalon, which involves a 1.5km swim (60 lengths in a 25m pool) and 40km on the bike, followed by a 10km sprint to the finish line.

Instead, Lannon swam 160 lengths before hopping on the bike. He completed the triathlon at his local gym, Greens, cheered on by friends and family.

"Just to say, 'I'm going to do a triathlon' wasn't enough," he explains. "I'm very competitive with myself, so I can't imagine racing against other people. I wouldn't like anyone to beat me!"

Lannon says his spirited resilience has developed because of his experiences with hydrocephalus, rather than in spite of it. "It has made me really, really self-reliant."

Most endurance athletes talk of "hitting the wall" at some point during a major event, but Lannon encountered no such difficulties. In fact, he had trouble stopping when he reached the end of the challenge. "I don't think the 'wall' is applicable to me, because of everything that I've been through," he says.

Lannon's mother first noticed a bump on the right-hand side of his head when he was three years old. She took him to the GP, who said there was nothing to worry about, before seeking a second opinion. He was referred for a scan and a cyst was found on his brain. Three years later, another cyst was found, and a shunt was fitted to drain off the excess spinal fluid, which runs from the cyst down the back of his head, close to the ear line. It resembles a bulging vein, only the plastic tube is uniform in shape.

More than 20 years later, he remembers the experience in detail, even recollecting what it felt like lying on the trolley for his first operation. "I wasn't happy about it. It was scary. I actually gave the porter a black eye!" As there was no quick-fix to Lannon's situation, operations and hospital stays became a way of life as he was growing up.

"After my first couple of operations I just thought: 'Get me in, get it done and get me better.' I wasn't bothered by what they were going to do to me."

Lannon has also had a piece of his skull removed from the right side of his head to create a sort of emergency decompression chamber for his brain: if the shunts are failing and the fluid builds up, the skin where the bone has been removed from will fill out and he will know that he must get to hospital as quickly as possible.

Conor Mallucci, the consultant neurosurgeon who has treated Lannon for the past 10 years, says: "You fall into two categories if you've got hydrocephalus. There's the unlucky category, where you have multiple shunt revisions and have complications throughout life, and that's Simon Lannon.

"For the lucky category, the shunt works well and you may have one or two operations, but no major complications. I've got one patient who has had more than 100 shunt operations.

"Hydrocephalus in isolation shouldn't shorten your life span," he explains. "Simon is unique in terms of activity for somebody who's been through what he has. He will almost certainly need future operations, but I think he's proved he's durable and strong."

Lannon first started to exercise when he was in his early teens. Overweight after a three-month course of steroids and undergoing a period of post-operative depression, he decided to get some fresh air. Walks soon turned into short jogs, the weight began to drop off and his confidence grew. A few years later, he started swimming and doing weights in the gym. His triathlon times are impressive: one hour 45 minutes for the 160-length swim, one and a half hours for the 40km bike ride and a swift 10km run to finish off, but he's not ready to hang up his goggles and running shoes just yet. Still in the planning stages are various inventive endurance events, through which Lannon hopes to raise a total of £60,000 for the Walton Centre, to mark the 60 years it has been treating patients with brain abnormalities. More than that, he believes he can help other people achieve their fitness goals, and is already giving motivational talks around Merseyside. "People place limits on themselves, and other people pose limits on people as well. It stops people from moving forward. If a 10, 11 or 12 year old wants to be a professional footballer, he's got to believe that he can be."

To sponsor Simon Lannon email triathlon4walton@btinternet.com, or contact the Walton Centre on 0151-525 3611.

What exactly is hydrocephalus?

Hydrocephalus is a condition where an excessive amount of fluid collects in the brain. The "water" is cerebrospinal fluid, which flows through passageways in the brain. If these get blocked, the liquid accumulates, widens spaces within the brain, and causes pressure on brain tissue. In babies, this can cause the head to enlarge. In adults, it can result in a variety of symptoms.

The most common triggers for hydrocephalus in children are infections, such as meningitis; premature birth, or head injuries. Genetic causes are rarer. Some experts estimate that hydrocephalus affects roughly one in 500 children. In adults, it can result from meningitis, a brain tumour or brain trauma.

Symptoms vary with age, the stage of the disease, and an individual's tolerance of the condition. An infant's skull can expand in response to the pressure of fluid, while an adult's cannot. Adults and older children may suffer from headaches, vomiting, nausea, blurred or double vision, poor coordination or lack of balance. Hydrocephalus can also result in incontinence, memory loss, irritability, lethargy, and lack of reasoning ability. Many born with the condition will lead full, normal lives.

The symptoms can overlap with other diseases – such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's – and are often misdiagnosed. Doctors sometimes need to conduct multiple tests, such as brain scans and spinal taps, to ensure accuracy. In infants, a rapid increase in head circumference is an obvious sign. An ultrasound can usually detect signs of hydrocephalus before birth.

There is no real cure, but the disease is usually treated with a shunt system – a plastic tube, a catheter and a valve. This is inserted to divert fluid from the brain to another part of the body, such as the abdominal cavity, where it can be absorbed without harm. Shunts usually stay in place for life, but can get infected; they may also need to be adjusted if a patient grows, rendering the tube too short. Hydrocephalus can also be treated by inserting a small fibre-optic camera into your body, allowing doctors to make a small hole in a brain ventricle.

By Iain Marlow

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments