Young, successful, busy yet lonely: A generation empowered by the internet and plagued by loneliness

Could a new friendship app be the key to tackling loneliness among millennials?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Podcasts are so popular because people living in busy cities are so lonely, I was informed by a friend the other day. While the research to back up that statement is somewhat lacking, the reasoning behind it is more compelling. The assuredness that should be enjoyed by smart, engaged, digitally savvy and successful 20 and 30 something-year-olds is, for an increasing number, overshadowed by a gnawing sense of isolation and loneliness.

Loneliness among young people is a problem that has been slowly uncovered in polls. Eighty-six per cent of millennials reported feeling lonely and depressed in a 2011 study. A study in 2014 found 18-24-year-olds were four times as likely to feel lonely all the time as those aged 70 and above.

It’s a feeling few feel comfortable saying out loud. Loneliness becomes a greater burden thanks to the social stigma inextricably linked to it and accepting it means accepting an often scary understanding of the lives we constructed for ourselves. Humans were built for companionship, not to be alone, at least according to the growing body of research on the effect social isolation has on health. Older adults are more at risk of developing dementia if they endure chronic loneliness is the conclusion of one often cited study, while a second claims a lack of social connections can be as dangerous as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

The insidious nature of loneliness is being increasingly explored thanks to research and campaigns launched in recent years, and this spotlight has been welcomed. The calls and emails that came in response to the New York-based journalist Julia Bainbridge’s The Lonely Hour podcast show how universal the feeling is. Many of those ringing in were grateful to hear a voice expressing something they were too terrified to vocalise, including one woman, who told Bainbridge: “It’s funny, or maybe it’s sad, that what brings us together is that we all feel lonely.”

Bainbridge says she launched the podcast after noticing loneliness appearing in various forms in lots of different places and realising how loneliness was also affecting her. In a forward to her second series, she explained: “I started this project because we seem to be experiencing a significant increase in social isolation and a decrease in connections to close friends and family. According to studies from the National Science Foundation, loneliness may be our next big public health issue. Those things are true, but what is also true is that I’m lonely. I’m a 33-year-old single woman in New York City who is looking for partnership at a time and a place when it seems particularly hard to find.”

First person accounts like Bainbridge’s are increasingly emerging but still relatively sparse, yet loneliness is experienced in some form by everyone to some degree. I purposefully spend most of my time surrounded by people. I am single but lucky to have an expansive social network that spreads across cities and I treat each friendship in the same way I would treat a relationship with a partner; as something that needs to be carefully maintained in order to endure. I even hesitated writing that sentence in case I could somehow jeopardise this wonderful network just by committing it to the internet.

I probably overspend because of how scared I feel of losing this network and I rarely decline an event with friends. A recent weekend spent in by myself after going for drinks with friends on a Friday evening left me practically crawling the walls and by the end of Saturday evening, I really wanted to buy a packet of cigarettes and I really wanted a glass of wine. I wasn’t bored, I had been productive: I had things to do and deliberately isolated myself. That 'crawling the walls' feeling was loneliness.

Is loneliness ever more pronounced than in the most every day situations: while eating dinner, while going to sleep? Social media has provided a space where people feel safe to express these moments of loneliness under tags, bringing together an online community of people who feel the same way. There are 400 million people on Instagram. At the time of writing, there are 4.7 million posts with the hashtag #lonely on Instagram. Almost one million tagged under #loner. Almost half a million under #loneliness.

Eve Critchley, the Head of Digital for the mental health charity Mind, says the sudden access we have to virtually every movement of our nearest, dearest and even those we only vaguely know through social media is creating a pervasive sense of FOMO (fear of missing out) that in turn perpetuates loneliness. There are 329 million #happy posts on Instagram, 3.9 million #relationshipgoals hashtags. Feeds are otherwise populated by heavily filtered images of holidays abroad in idyllic locations, mouthwatering meals consumed in trendy locations - who’s to know the off-the-cuff picture took five attempts, the holiday was boring, tempers were frayed or the food was cold? How many posts are there about having a #terribletime? 915 at the time of writing, to be precise.

The Couple Goals Instagram page has 4.3 million followers

“This can stir up several emotions and there has been a suggestion that comparing ourselves to one another could contribute to depression or other mental health problems,” says Critchley. “While there is no formal evidence to suggest this, it easy to see that if you’re already feeling low, entering a space where you’re faced with only the best aspects of other people’s lives could lower self-esteem.” A vicious cycle of low self-esteem further damaged by feeling less happy or connected than others is fostered, she adds. “If you have low self-esteem, your beliefs about yourself will often be negative. You will tend to focus on your weaknesses or mistakes that you have made and may find it hard to recognise the positive parts of your personality. You may also blame yourself for any difficulties or failures that you have.”

Experiences shared online in forums and on Reddit threads such as NeedaFriend show how easily alienation can develop into isolation.

“I'm 19 and from London. I have always struggled to make friends and am getting worse. I don't have any people I can really do things with. I have met people on the internet and even this very website but it rarely lasts. I no longer want to just have people I converse with over a screen. Anyone I sort of get close to, they disappear.”

“I'm 18 and in my first year at university and am unable to make friends. I'm friendly with my flatmates but I wouldn't call it a real friendship because they don't seem to want to spend time with me and are usually with their boyfriends or other friends which makes me feel even more lonely.”

“I'm […] 22 and from the UK. I just graduated college with my bachelors in Business Economics in the summer and following that I was living/travelling in the North East of the USA for like two months. I'm really just looking to make more long term, genuine friends online now that I'm done college. My friendship group has dwindled over the years and now I'm not in college every day it's a bit more lonely, I guess.”

***

Open the home screen on your phone and an array of home buttons await, a literal virtual reality. There is enough technology encompassed within these icons to ensure someone would never need to leave the house if they were really set against the idea. People can manage their finances and apply for a loan on an app. There are apps promising to help users meet the love (or, as is often the case, lust) of their life, or just to organise it. Apps for those seeking a more causal or even extra-marital encounter. Anxiety can be tackled with mindfulness apps. Heating and lights can be switched on and off with apps. There are apps for health and to diagnose illness. Apps exist promising to transfer useful skills and languages.

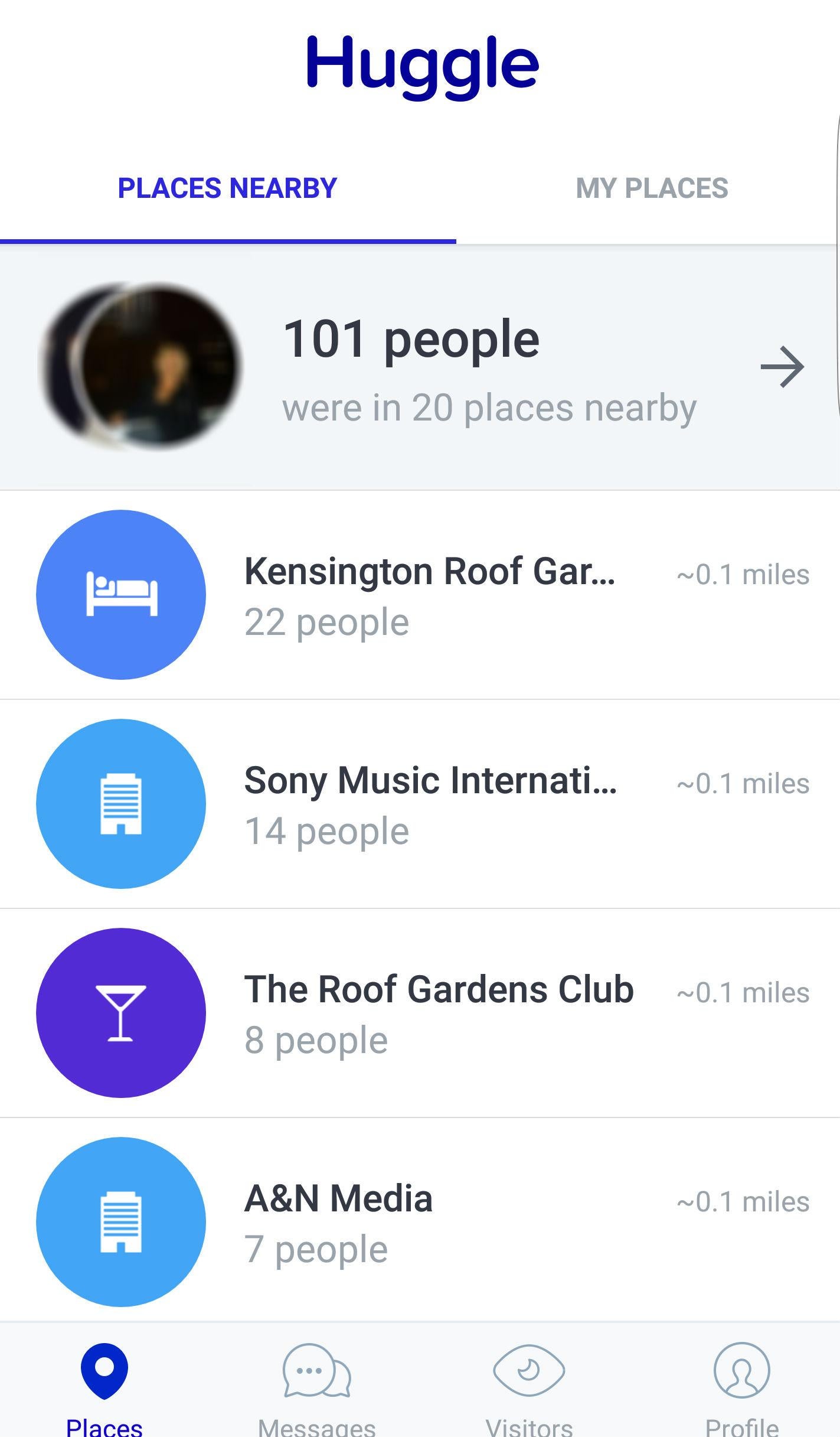

Huggle is an app hoping to tackle loneliness by helping its users build connections with people who share common interests, interests which are determined by the places they go - restaurants, yoga classes, cocktail bars. But many would argue technology is the reason we are so isolated, that it has become the commodity disconnecting us from others in giving us screens to hide behind. The question then is whether an app could actually help alleviate loneliness?

Huggle co-founder Valerie Stark has first-hand experience of crippling loneliness. Successful and ostensibly well-connected, she speaks about being lonely with surprising candour. Her loneliness would manifest itself in the solitary dinners she would eat in trendy restaurants, in failed attempts at talking to other diners which she said only resulted in her seeming somewhat manic. After moving from Moscow to London to manage restaurants, she immersed herself in the things she enjoyed, believing she would organically form friendships with like-minded people in the same scene; joining yoga classes and gyms, going for lunches at popular venues in the hope of meeting like-minded foodies who she could bond with over shared passions.

“It was a new city, new country, and in my dream it was like I was going to yoga, and I would be like ‘hey, how are you’ to the girl next to me on the mat. Or I would be like, sitting there drinking coffee and casually say ‘nice leggings’, or something. But you know, that’s how you imagine things. You move to a new city, and you’re like… that’s easy. [At least,] I envisioned that. I started doing yoga, and people were so into themselves, and obviously you don’t just say hi - it’s just creepy and then you just end up concentrating on your own practice and nothing happens. And then you go to a restaurant and people just sit how we sit right now; they talk to each other, not to people on the next row.

“I was going everywhere by myself. At some point I went, oh my God - I’m 26 years old. I only had a couple of close friends and one best friend [who did not live in the UK]. And so, yeah you don’t approach people, you go to a restaurant, you’re on your own, and sometimes I thought, well I’m going to become an alcoholic because you just drink [when you are eating out alone].”

Her efforts were not limited to real world interactions; these were attempts she made online as well in her love for organic gardening, trying to grow her own community through her blogs. But making relationships transcend computer screens can prove easier said than done. “I was doing organic gardening, growing my vegetables, I had a really big following and I had 40,000 followers, but it didn’t help me. I was talking to them, and they were like ‘yeah, great tomatoes’, but it didn’t really get to the point where you go ‘alright, let’s be friends’.

“I’m on my own. Literally, on my own. I was born in a busy city, I thought, ok, I can make friends there, I’ll be fine here, but it didn’t happen that way. And I was obsessively trawling through Instagram and I would check myself into all the places I like to go, and I was like, how is this possible, like these people, they’re supposed to be like me, like the same thing - why are we not friends? How [do I] become friends with them?”

Stark was this lonely for a year.

“I was really depressed. I had people I knew here but they were people who were helping me, or like one girl helped me find accommodation when I moved in. She was an estate agent and literally I would go with them somewhere out once every three weeks. Just for the sake of not being on my own.”

Connections is the buzz word with Huggle, an app that Stark says can tackle loneliness and engender the birth of those meaningful interactions so many are craving by matching people by their interests, thereby encouraging them to get from behind the computer screens and meet in real world settings. Launched alongside former model and blogger Stina Sanders, Huggle was inspired by both of their experiences of loneliness. Sanders hails from a small town in Bath and says her isolation was a product of living in a busier environment and an ongoing struggle with anxiety. “I think when anyone comes from outside of London and they come here for the first time, it’s lonely,” she says.

Both Stark and Sanders believe one of the biggest problems with our fear of loneliness is when friendships begin to break down because a lack of common interests or beliefs, but people are too worried about being alone to end them. Instead, they maintain these friendships which only serve to make them feel more alienated.

“It’s loneliness,” says Stark. “They don’t want to break up, whether it’s a friendship or a relationship. We grow, that’s fine. And you need to have the courage to admit it. But there is no way to ditch your friend. In a relationship you say, ‘you know what, don’t call me anymore’.”

The app will not disclose when people check into the same place at the same time for safety reasons. Instead of manual check-ins, it uses hyper-location technology to automatically check people in. What Stark and Sanders hope from their app is that by connecting people in this way, it encourages them to step away from the computer screens and meet face-to-face in the spaces they already both enjoy, feeling more comfortable in the knowledge they share interests.

“I think technology is great and it connects people,” adds Sanders. “I understand why people are saying it disconnects [people] because we were just saying we have so many friends – yeah, you have a thousand Facebook friends, and actually, you’re disconnected because you don’t really know them and you have nothing in common, but when technology is used in the way we use it, you are better connected in that way.

“We’re using online experience to get people offline. Because we want them to start moving. In order to collect places they have to go to places, at least you have a university in common, or go to this restaurant, you need to live.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments