How slimming became an obsession with women in post-war Britain

The end of food rationing marked the beginning of a modern slimming culture, which has since permeated all aspects of women’s lives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When regular Woman’s Own contributor Eileen Fowler advised readers in October 1954 on how to lose weight, rationing had only been abolished for a few months. Despite the hardship of recent food shortages, her three-part illustrated series, “Trim your figure”, left women in no doubt: chores such as polishing and dusting should be performed in such a way as to enable the British housewife and mother to keep slim, or return to her pre-pregnancy figure. The end of food rationing marked the beginning of a modern slimming culture, which has since permeated all aspects of women’s lives.

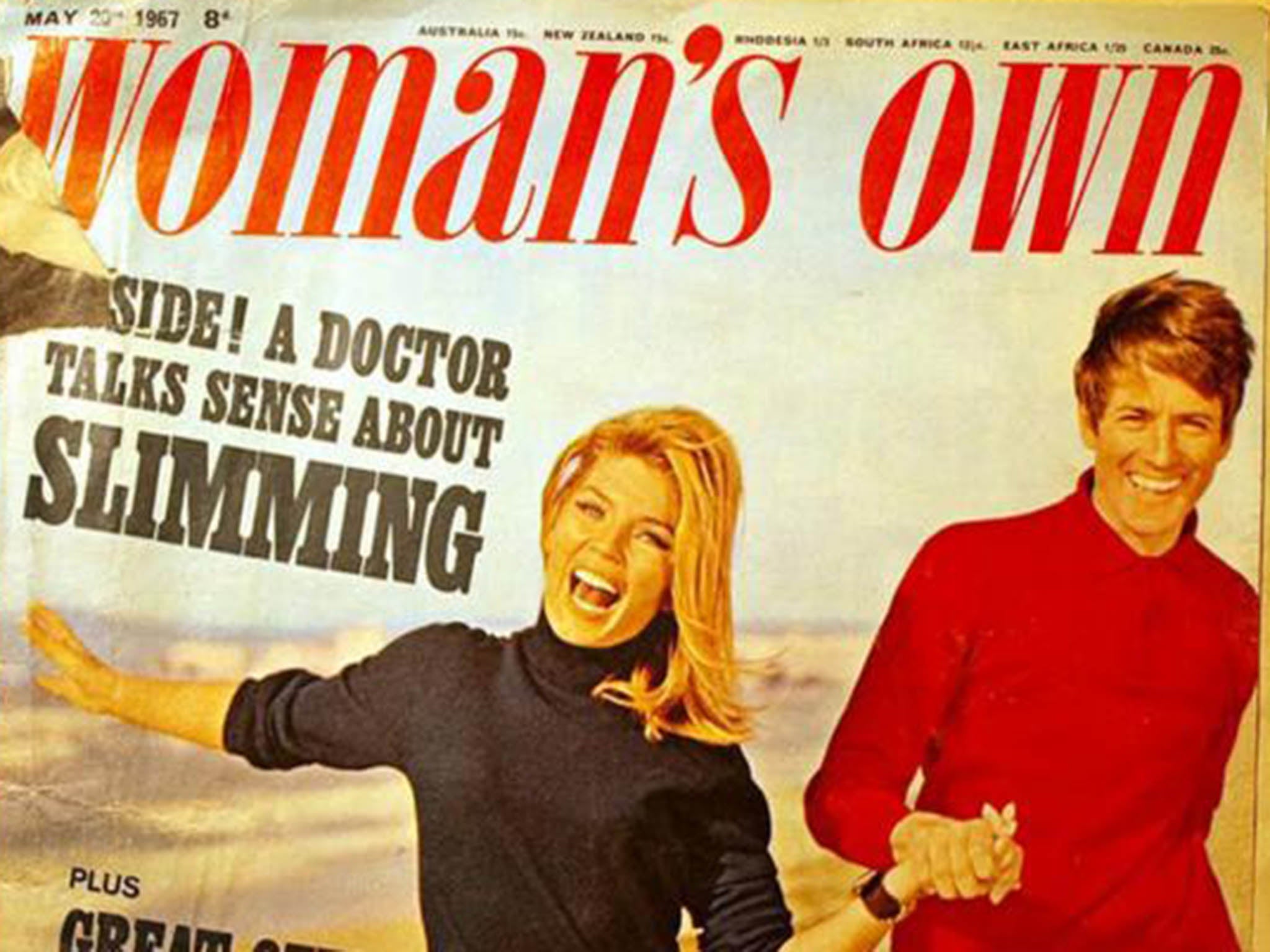

Woman’s Own, one of the most popular post-war women’s magazines in the country, pursued this emerging slimming mantra with vigour, and by the mid-1960s had elevated dieting to centre stage of its weekly beauty advice. Not unlike modern counterparts, the magazine published countless diet and exercise articles promoting female slimness as an ideal of post-war femininity. Clearly, long before Susie Orbach identified fat to be a feminist issue in 1978, it had already developed into a capitalist one.

Surprisingly, weight-loss diets in the 1950s and 1960s were not too dissimilar from today’s diets. In the 1950s, the focus was on minimising carbohydrates, and in the 1960s, it was on low-fat, low-calorie meals. Diets peddled by today’s women’s press are more often than not repackaged versions of meal plans published 50 years ago. Post-Christmas diets, steak diets, beach-body diets… they’ve all been around for much longer than people realise.

While the rise of the weight-loss industry is often seen as a recent phenomenon of modern consumer societies, characterised by the abundance and affordability of foodstuffs, research into Woman’s Own shows slimming diets were circulated even during times of austerity. Early post-war articles, when rationing was still in place, advised cutting down on bread, potatoes and carrots.

As early as 1945, a Woman’s Own article on corsets encouraged women to exercise caution at mealtimes, since “war-time rationing has led to an increased consumption of starchy fattening foods, with unflattering results to our figures”. In order to lose weight, the article recommended reducing the number of meals and cutting down on bread, potatoes, cakes and biscuits.

Cutting down on carbohydrates was repeated in all of Woman’s Own weight-loss articles published during rationing. They were often coupled with liquid-, fruit- or vegetable-only days. An exemplary diet (“Figure perfect?”), published in 1950, encapsulates this frugal approach: fresh fruit for breakfast, salad and lean meat for lunch, any meat or fish with a generous helping of green vegetables for dinner. Following this simple plan would “tackle those surplus pounds” amassed during winter, a season that, according to Woman’s Own, “has a nasty habit of adding curves we don’t need”.

Starving in times of plenty

As rationing ended – and shortages subsided and gave way to increasing affluence in the late 1950s – the economical nature of Woman’s Own slimming advice also changed. Readers were now encouraged to prepare more elaborate diet meals and significantly limit portion sizes and calorie content. Carbohydrates, however, remained largely absent from weight-loss advice and only began to appear on slimmers’ menus when the magazine changed its overall nutritional emphasis in the mid to late 1960s.

This shift saw Woman’s Own increase its promotion of slim figures by offering a range of methods, from the “no-diet diet”(1966), to the “three-day-pounds-off-liquid diet” (1970). The magazine encouraged its readers to try whatever weight-loss regime was necessary to achieve the desired shape.

Between 1966 and 1970, the magazine offered 40 different – often polar-opposite – approaches to weight loss, including many fad plans, such as the “meat-only diet”, “banana and milk diet”, “day-in, day-out diet”, “fruit only diet”, “buttermilk diet” and the “350-calorie air hostess diet”. This particular, extremely low-calorie diet from 1969 clearly meant to appeal during the jet age, when stewardesses were widely regarded as glamorous icons of femininity. While employment criteria set out by airlines would today be considered as outright sexist, many women aspired to becoming a “stargirl”, but could only make the grade if they were young, single and slender.

A diet of only 350 calories per day, as proposed by Woman’s Own, would undoubtedly bring about the required physique. (Incidentally, weight restrictions for flight attendants are still in place today, although the definition is somewhat broader than in the 1960s and linked to a person’s body mass index.)

The magazine urged its readers to eat bread and count calories one week, while banning all forms of carbohydrates and calorie counting the next. Some diets remained far below 1,000 calories per day – one article from 1969 recommended a daily energy intake of between 350 and 900 calories and asked its readers to consume “one hard-boiled egg and one small tomato up to six times a day – only when you feel hungry”. The instructions added, perhaps unnecessarily, that: “Fat vanishes amazingly fast”.

Woman’s Own did not always consider exercise to be beneficial for weight loss. In the 1950s, it was understood to be, at best, less effective than dieting and, at worst, considered to be counterproductive to weight loss.

While slimming diets were to lower body weight, most exercise advice was aimed at reducing “trouble spots” or “problem zones”. These were defined by the magazine as a woman’s tummy, buttocks, waist, hips, bust, arms, ankles and wrists. According to Woman’s Own (1954), losing weight in these areas was best achieved by blending household chores with exercise and combining workouts with activities such as “picking up and carrying around the baby, washing and ironing its clothes”.

Losing weight after giving birth was of particular concern to the magazine. It advised its readers that “as soon as baby is born, begin your daily exercises, so that you will regain your figure in the shortest possible time” (1955). Further evidence for the magazine’s stance on a wife’s and mother’s “duty for beauty” is provided by another article from 1955, in which the author reminded the readers that, above all, women must not “let themselves go” after pregnancy. The author instructed mothers to remember that “you’re still a wife as well as a mother – so you want to stay attractive”.

Looking good for your man

The argument that a woman’s worth was reflected in her husband’s judgement, was repeated time and again. The magazine described how men would become naturally disgruntled if their wives “let themselves go” after a few years of marriage and motherhood. The link between body weight and a woman’s reproductive life was repeated in the early 1960s, when Woman’s Own pointed out that women were to groom themselves and keep trim figures during the menopause. The emphasis was most often placed on a woman’s duty to keep her youthfulness through a slender physique, suggesting that a slender figure was needed to look pretty in the latest fashions.

But it was not just postpartum or menopausal weight gain which the magazine focused on. Woman’s Own also linked “good mothering” to body weight and at one point exclaimed that “not only are fat women worse risks as mothers – they also have more complications in childbirth and a higher degree of deaths among their unborn children”.

Another angle to the imperative of “slim wifedom” was provided by an article of 1956, headlined: “How to be a better wife”. Upon her husband’s unfounded remark that she was becoming much too fat, his wife realised that it was, in fact, hubby who was worrying about his weight, but couldn’t bring himself to admit it. But instead of standing up for herself – it was, after all his problem, not hers – she said she would be “quite happy to cooperate because we are told that extra pounds take years off a man’s life”. She finished up by reminding the reader that it is a wife’s duty to keep her husband happy, even if, as in this case, it meant pretending to be overweight herself.

With the advent of second-wave feminism in the mid 1960s still a few years off, this story perfectly illustrates the magazine’s stance of a woman’s traditional role in relation to her husband during the post-war years.

Even when the inclusion of men in Woman’s Own weight-loss articles increased in the late 1960s, it was made clear that women are the weaker sex: male slenderness was depicted as vital for a man’s health and portrayed as an outward sign of his financial success and sexual prowess. In 1966, the magazine published the story of a male slimmer who reluctantly went on one of Woman’s Own’s low-carbohydrate diets only to discover that cutting out beer, bread and potatoes significantly enhanced his professional status and provided the stamina required for impending fatherhood.

The description of the male slimmer was in stark contrast to that of female dieters. A woman’s journey to a slim body was usually described as being hampered by her uncontrollable food cravings and moods, as governed by the stages of her reproductive life cycle.

Overall, the late 1960s saw Woman’s Own continue to promote a slim figure as a woman’s “must-have” accessory. But what had markedly changed was not just the nutritional content of its diets, but its undertones. A slender figure was no longer just promoted as a necessary means for women to fulfil their roles as wives and mothers, it was coupled with general messages of health, beauty and “vitality”, and increasingly promoted weight loss as a form of “self-help” – by now, often achieved within a slimming group.

This change was in step with a shift in the general content of Woman’s Own during the same period. From 1967 onwards, the magazine increasingly published articles on women’s struggles for more independence, job prospects or education, reflecting, perhaps, the changing experiences of its readership. Indeed, the quest for equality in the 1960s was not necessarily at odds with the rise of the consumer society.

More and more married women entered the workforce from the late 1950s onwards, and there was a growing public debate and awareness of women’s changing role in society. So how was it that, during this period, a slim female beauty ideal, to be achieved via generally severe methods, became a deeply entrenched norm that still exists in the 21st century? Certainly, Woman’s Own’s focus on the “duty for beauty” – and with it for a slender body, remained and even increased in intensity.

Weight loss was no longer a matter of simply cutting out carbohydrates. Now, any method would do as long as the required body shape was achieved – whether that was the body of the stereotypical 1950s homemaker, or that of the equality-conscious working woman of the late 1960s did not matter. The theme of women’s liberation became effortlessly incorporated into Woman’s Own’s promise of a thin body.

The obesity crisis begins

The magazine’s increased focus on dieting during the 1960s was partly driven by concerns over an impending obesity crisis, as it was then that evidence for the detrimental effects of over-consumption became more widely known. Although the prevalence of obesity was comparatively small in the 1960s, research on associated conditions such as heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes, began to make headlines. This followed the publication of the “Build and blood pressure study” in 1959 by US insurance companies – which, at the time, represented the largest body of information relating body weight to mortality, and which was quickly adopted, worldwide. As Woman’s Own rather bluntly put it in 1969:

No one wants to be fat. Not just because overweight – as statistics prove – is a recognised health danger; not just because it looks unsightly and ridiculous in trendy fashions. But because being too fat diminishes your identity. All fat people tend to look alike. Fat has a knack of ironing and flattening out the features, obliterating them.

Obesity research fuelled a growing slimming culture and increased the popularity – and number – of slimming clubs, replacement foods and weight-loss diets in the late 1960s. Between 1966 and 1970, the magazine regularly published weight-loss articles promoting the consumption of slimming liquids and biscuits, commercial slimming foods and artificial sweeteners.

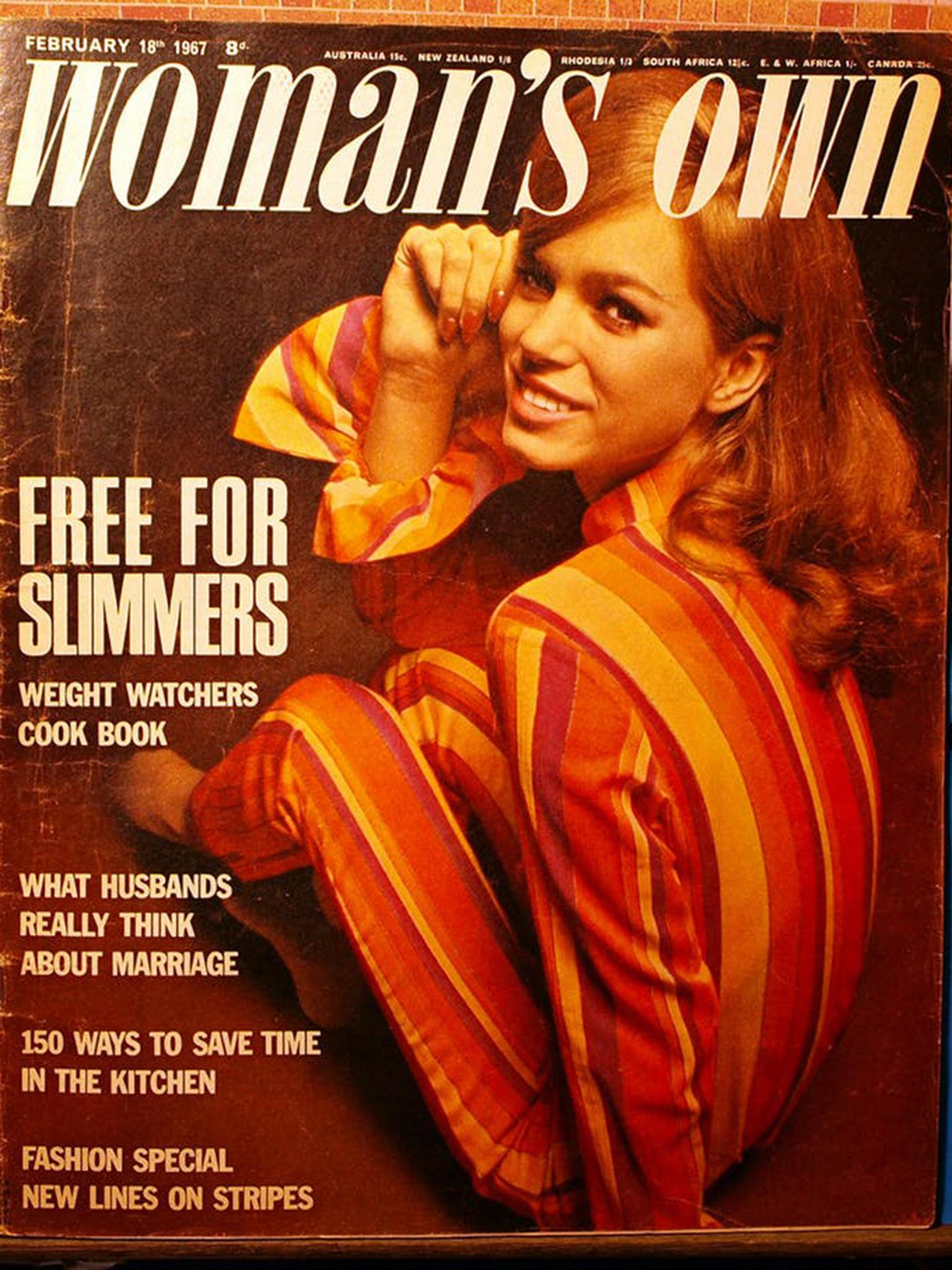

Further evidence for Woman’s Own embracing the developing commercial slimming culture in the late 1960s and early 1970s, is that of the magazine’s promotion of slimming clubs. Here, Woman’s Own published a Weight Watchers pull-out cookbook as early as 1967, pointing to the success of the idea that “has spread like wildfire in Canada and the US”. The woman’s weekly also teamed up with its British equivalent, Silhouette Slimming, offering pull-out diet booklets and vouchers for a reduced registration fee.

In the age of post-war affluence and rising body weights, commercial forces recognised early on that the propagation of a slim ideal would prove lucrative. And women’s magazines provided the ideal platform to transmit these messages and so were instrumental in the dissemination and entrenchment of a thin ideal to aspire to.

The location of a slim beauty ideal within the context of a woman’s traditional post-war role and reproductive life cycle typified slimming advice in Woman’s Own during the 1950s and 1960s. A slender female body was meant to please, although not necessarily women themselves. And external recognition, granted merely on the merit of physical beauty, was supposed to lead to women’s self-fulfilment in their traditional roles as wives and mothers.

Given the context of the immediate post-war years and the magazine’s socially conservative stance, this finding is hardly surprising. What is startling, however, is how little the core message on slimming has changed since. Many weight-loss diets published in contemporary women’s magazines are simply repackaged versions of those in circulation half a century ago.

The “rationale” for a slender body given by today’s women’s press has also remained strikingly similar: a slender body is still overwhelmingly associated with beauty, desirability and self-fulfilment. It seems that only the terms have changed, since women are no longer confined to housewifery and motherhood. But despite women’s changing social roles and responsibilities, the different stages of her reproductive life still loom large in today’s weight-loss advice, with magazines continuing to praise or scold the ability to control post-partum or menopausal weight gain.

Whatever advice is given, the panacea for weight loss is as elusive as it has always been. This, clearly, is exploited by the weight-loss industry, for which women’s magazines have always provided a platform. With its high failure rates, the slimming market is a gift that keeps on giving – something that Woman’s Own already understood some 60 years ago.

Myriam Wilks-Heeg is a lecturer in 20th century history at the University of Liverpool. This article was originally published on The Conversation (conversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments