Why mothers should not feel guilty about spending no time with their children

'I could literally show you 20 charts, and 19 of them would show no relationship between the amount of parents’ time and children’s outcomes'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Do parents, especially mothers, spend enough time with their children?

Though American parents are with their children more than any parents in the world, many feel guilty because they don’t believe it’s enough. That’s because there’s a widespread cultural assumption that the time parents, particularly mothers, spend with children is key to ensuring a bright future.

Now groundbreaking new research upends that conventional wisdom and finds that that isn’t the case. At all.

In fact, it appears the sheer amount of time parents spend with their kids between the ages of 3 and 11 has virtually no relationship to how children turn out, and a minimal effect on adolescents, according to the first large-scale longitudinal study of parent time to be published in April in the Journal of Marriage and Family. The finding includes children’s academic achievement, behavior and emotional well-being.

“I could literally show you 20 charts, and 19 of them would show no relationship between the amount of parents’ time and children’s outcomes. . . . Nada. Zippo,” said Melissa Milkie, a sociologist at the University of Toronto and one of the report’s authors.

In fact, the study found one key instance when parent time can be particularly harmful to children. That’s when parents, mothers in particular, are stressed, sleep-deprived, guilty and anxious.

“Mothers’ stress, especially when mothers are stressed because of the juggling with work and trying to find time with kids, that may actually be affecting their kids poorly,” said co-author Kei Nomaguchi, a sociologist at Bowling Green State University.

That’s not to say that parent time isn’t important. Plenty of studies have shown links between quality parent time — such as reading to a child, sharing meals, talking with them or otherwise engaging with them one-on-one — and positive outcomes for kids. The same is true for parents’ warmth and sensitivity toward their children. It’s just that the quantity of time doesn’t appear to matter.

“In an ideal world, this study would alleviate parents’ guilt about the amount of time they spend,” Milkie said, “and show instead what’s really important for kids.”

But if Milkie’s study makes clear that quality, not quantity, counts, then how much quality time is enough? Milkie’s study doesn’t say.

“I’m not aware of any rich and telling literature on whether there’s a ‘sweet spot’ of the right amount of time to spend with kids,” said Matthew Biel, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at Georgetown University Medical Center.

Research does show that in highly stressed urban environments, having involved parents and even strict parents is associated with less delinquent behavior, Biel said.

In truth, Milkie’s study and others have found that, more than any quantity or quality time, income and a mother’s educational level are most strongly associated with a child’s future success.

“If we’re really wanting to think about the bigger picture and ask, how would we support kids, our study suggests through social resources that help the parents in terms of supporting their mental health and socio-economic status,” she said. “The sheer amount of time that we’ve been so focused on them doesn’t do much.”

Amy Hsin, a sociologist at Queens College, has found that parents who spend the bulk of their time with children under 6 watching TV or doing nothing can actually have a “detrimental” effect on them. And the American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes that children also need unstructured time to themselves without the engagement of parents for social and cognitive development.

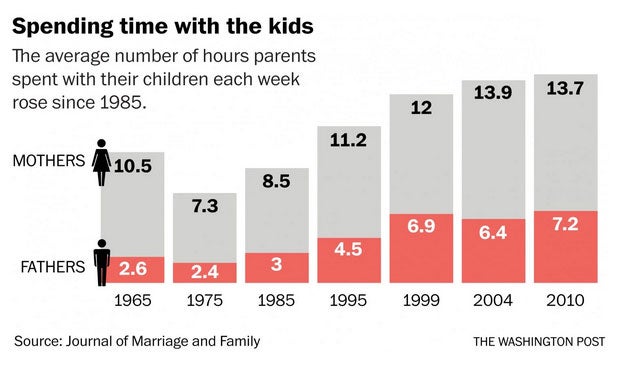

Still, the amount of time mothers and fathers spend in child care has been climbing since the 1970s. Fathers’ time has nearly tripled from 2.6 hours a week spent with kids in 1965 to 7.2 in 2010. Mothers’ time with children rose from 10.5 hours a week in 1965 to 13.7 in 2010. In roughly the same period, the share of working mothers with children under 18 rose from 41 percent in 1965 to 71 percent in 2014.

In fact, working mothers today, an earlier groundbreaking study of Milkie’s found, are spending as much time with their children as at-home mothers did in the early 1970s. It was that surprising finding that led Milkie to wonder — does all that time make a difference for kids?

In her current work, though she looked at father time and parent time together, Milkie focused specifically on mothers. She wanted to test the widespread belief that there’s “something special” about mothers’ time with children. Milkie predicted mother and parent time with kids would matter. She was shocked when she found it didn’t. “I was really surprised,” she said. “And we don’t find mothers’ work hours matter much at all.”

The one key instance Milkie and her co-authors found where the quantity of time parents spend does indeed matter is during adolescence: The more time a teen spends engaged with their mother, the fewer instances of delinquent behavior. And the more time teens spend with both their parents together in family time, such as during meals, the less likely they are to abuse drugs and alcohol and engage in other risky or illegal behavior. They also achieve higher math scores.

The study found positive associations for teens who spent an average of six hours a week engaged in family time with the parents. “So these are not huge amounts of time,” Milkie said.

The researchers analyzed the time diaries of a nationally representative sample of children over time, looking at parent time and outcomes when the children were between the ages of 3 and 11 in 1997, and again in 2002, when the children were between the ages of 12 and 17. Researchers looked at both “engaged” time, when parents were interacting with their children, and “accessible” time, when parents were present, but not actively involved with children. They focused on sheer quantity, not quality, of time. They did not look at time with children from birth to the age of 3.

Nomaguchi said mothers’ guilt-ridden efforts to spend as much time as possible with their children may be having the opposite effect of what they intend.

“We found consistently that mothers’ distress is related to poor outcomes for their children,” including behavioral and emotional problems and “even lower math scores,” Nomaguchi said.

Indeed, some of that stress, the researchers say, may be driven by what they call “intensive mothering” beliefs that have ratcheted up the standards for what it takes to be considered a good mother in recent decades. The idea that mothers’ time with children is “irreplaceable” and “sacred,” they contend, has led to mothers cutting back on sleep and time to themselves in order to lavish more time and attention on their kids.

“There are a lot of cultural pressures for intensive parenting — the competition for jobs, what we think makes for a successful child, teenager and young adult, and what we think in a competitive society with few social supports is going to help them succeed,” Milkie said.

Low-income mothers, who have traditionally not been associated with time-intensive, middle-class “helicopter parenting,” Milkie said, not only have more financial and day-to-day stress, but may also feel stressed that they don’t have the resources to keep up with intensive parenting expectations. “They’re getting the same message, that spending time with kids is important,” she said.

Nicole Coomber, a management professor at the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business and mother of two boys, said she feels that pressure to intensively parent more than her husband does. “No one ever asks him how he’s managing to balance it all,” she said. And sometimes she puts higher expectations on herself. “I don’t know why it is that I’m trying to be the perfect mother, but I definitely am. That voice in my head is not very gentle.”

Her husband, Bob, wants to spend more time with their children than his father, a traditional breadwinner, spent with him, and mornings are chaotic as he gets the kids out the door and to child care. But he doesn’t feel the intense pressure to spend more time with the children and meet high parenting expectations that his wife does.

“It’s like I have the role model of my dad, and I’m kind of following in that model,” he said. “But she thinks she has to be my mom, who stayed at home with us for most of our formative years before going back to work, and be a successful professional. And it’s impossible to do both.”

Jennifer Senior, who chronicled intensive parenting in “All Joy and No Fun,” attributed the guilty feeling that parents — mothers especially — can’t spend enough time with their children to a nostalgia for the past and a continuing ambivalence about working mothers. The General Social Survey, which has tracked Americans’ attitudes and opinions since 1972, for instance, still asks whether children would be better off with mothers at home, and whether working mothers can form strong bonds with their children. The results are mixed. The survey does not ask the same questions about fathers.

“Perhaps if you were part of a culture that actually felt less ambivalent about mothers working, and had a system of child care in place where it was okay for mothers to work, I think you would automatically feel less guilt and pressure to spend more time with kids,” she said.

The study’s findings shook some parents, many of whom had built their lives around the idea that the more time with children, the better. They quit or cut back on work, downsized their houses or struggled to cram it all in.

Mari Kosin, of Seattle, quit her full-time job in 2013 to stay home with her two children, ages 7 and 4, because the strain of managing work, the commute, child care, activities and home demands, and the guilt of being away from her daughters, or being snappish and always feeling rushed with them, got to be too much. The family has burned through its savings and is striving to afford living on a single income. Her reaction to the study: “Oh, I was afraid of that,” she said. “I can see from my own experience how time with your parents is more important in adolescence. But, you know, the relationship with your child isn’t built all of a sudden when they’re teens. It takes time early on.”

Building relationships, seizing quality moments of connection, not quantity, Milkie said, is what emerging research is showing to be most important for both parent and child well-being. “The amount of time doesn’t matter, but these little pieces of time do,” she said. Her advice to parents? “Just don’t worry so much about time.”

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments