Why living near an airport could be bad for your health

Studies reveal link between areas with high noise pollution and an increased risk of heart disease and stroke among residents

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Anyone who has ever lived under a flight path will tell you that the constant din of jet engines is more than enough to raise your blood pressure.

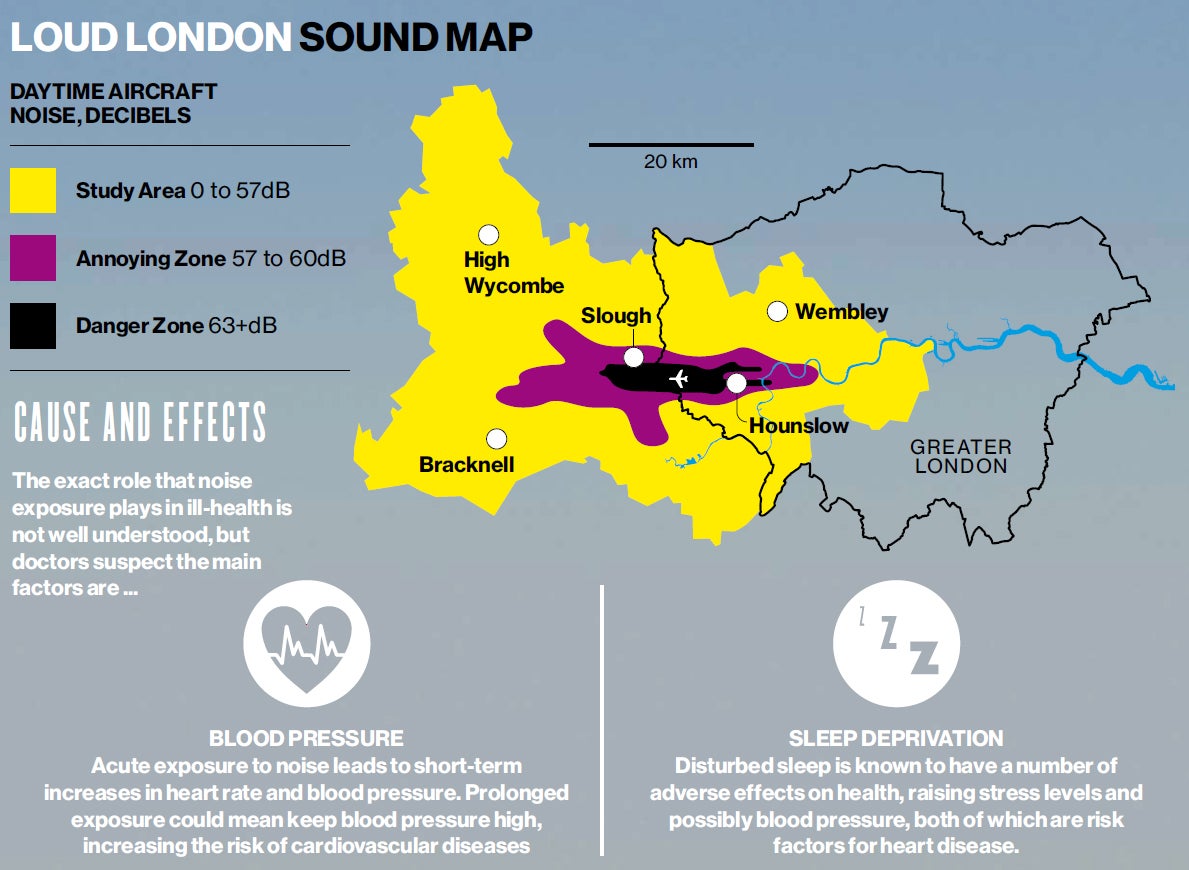

Click image above to enlarge graphic

But now researchers are warning for the first time that there may be a real health risk associated with aircraft noise. Two studies, published today in the British Medical Journal, found evidence that people living in areas with high levels of noise pollution from passing aeroplanes had a higher risk of heart disease and stroke.

The first study compared Civil Aviation Authority data on aircraft sound levels with hospital admissions and mortality rates for 3.6 million people living near Heathrow Airport, in areas where aircraft noise exceeded 50 decibels – the level of normal conversation in a quiet room.

Researchers from Imperial College London and King’s College London found that the risks of cardiovascular disease were greater for those living in neighbourhoods with highest noise levels and closest to the airport, such as Slough and Hounslow. Around 72,000 people living in the noisiest areas had a 10 to 20 per cent greater risk than people living in the quietest areas, researchers estimated.

A second investigation carried out in the US looked at heart disease among 6 million people living close to 89 airports. More than two per cent of hospitalisations for cardiovascular diseases could be attributed to aircraft noise, the researchers from the Harvard School for Public Health and the Boston University School of Public Health said.

Previous studies have suggested a link between a noisy environment and high blood pressure. Loud noise can lead to short-term increases in blood pressure, and sustained exposure could lead to more long-term risk. Scientists also proposed that night-time aircraft noise could be disturbing people’s sleep, which is another risk factor for heart disease.

Although health leaders in the UK stopped short of confirming a causal link between aircraft noise and heart problems, the studies show a strong association, which they said should be taken into account in future plans to expand airport capacity.

The findings come just days after the chairman of the Airports Commission Sir Howard Davies, the man tasked with solving the problem of the South East of England’s airport capacity, said that he would consider adding a third runway at Heathrow and a second runway at Gatwick.

Professor Paul Elliott, from the Centre for Environment and Health said: “The issue here is particularly with areas with the highest levels of aircraft noise. How can you design your future airports and airport capacity [while] trying to keep the exposure to the population below those highest levels? That’s [a question] the policymakers have to take into account. They’re already well aware of the annoyance levels. What we’re adding into the mix is that there may also be an effect on risk of heart disease.”

The Heathrow study covered 12 London boroughs and nine districts outside London. The study area was divided into 12,110 zones with a population of around 300 people each. Data on the noise levels for each small area in 2001, provided by the Civil Aviation Authority, was compared with information from the Office for National Statistics and the Department of Health on hospital admissions and deaths from cardiovascular disease between 2001 and 2005.

The results were adjusted to account for other heart disease risk factors, such as social deprivation and air pollution – although the area-based analysis made separating risks associated with factors such as smoking and ethnicity difficult.

In an editorial for the BMJ, Stephen Stansfeld, professor of psychiatry at Barts and London School of Medicine, said that the results “imply that the siting of airports and consequent exposure to aircraft noise may have direct effects on the health of the surrounding population. Planners need to take this into account when expanding airports in heavily populated areas or planning new airports,” he said.

Matt Gorman, Heathrow’s director of sustainability, said that the airport was already taking “significant steps” to reduce noise pollution by charging airlines more for louder aircraft and offering insulation and double glazing to local residents.

“Together these measures have meant that the number of people affected by noise has fallen by 90 per cent since the 1970s, despite the number of flights almost doubling. We are committed to ensuring this reduction continues,” he said.

A spokesman for the Airports Commission said: “We are aware of this report and will consider its findings. Environmental impacts, including levels of noise, are within the scope of our considerations and are something we are already looking at.”

Case study: ‘I can hear a plane every 90 seconds’

Margaret Thorburn, 59, lives in Osterley, London, under the Heathrow flight path

"These findings are alarming. Yet they reinforce what many of us living here have suspected for a long time. I have lived in Osterley for 30 years and have been diagnosed with high blood pressure.

“What people don’t realise is that it’s not just the sound of the aircraft – but how you have to adapt your entire audio environment. Everything in the house has to be louder to block out the noise; while your subconcious thought patterns are continuously interrupted.

“Over the years I have no doubt this has taken its toll on my anxiety levels.

“For all you hear about more advanced and quieter planes, the frequency of take-offs and landings are more than I ever remember. It’s not unusual for my day to be interrupted every 90 seconds. At the age of 59, I may well consider moving. But there are many of us that simply don’t have that option.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments