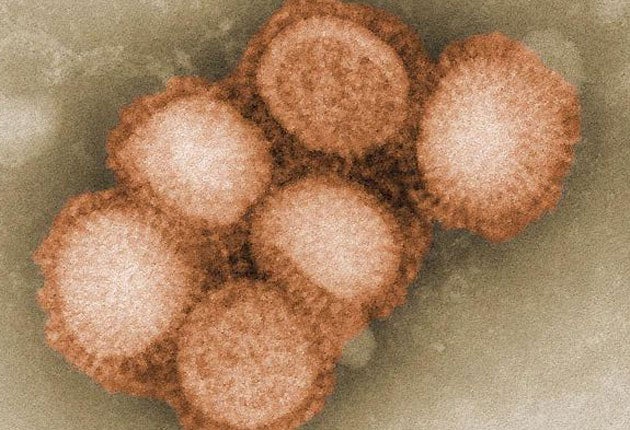

Why is the UK a swine flu hotspot?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the global swine flu pandemic gathers pace, one question is puzzling scientists. Why is a small country on the eastern seaboard of the north Atlantic so badly affected?

Britain is among the top half dozen global hot spots for swine flu. Along with Mexico, where the disease orginated, the US, Canada, Chile, Argentina and Australia, we are leading the way in the battle against the bug. We have more cases, and more deaths, than any other country in Europe and the pandemic is growing exponentially here, with 55,000 new cases last week, while it is subsiding elsewhere, notably in Mexico. And because we are in the front line, we are having to learn as we go.

This is not what was expected. Britain is an island nation, accustomed to the security that living within sea borders brings. But when it comes to highly pathogenic viruses, even the English channel cannot protect us.

When the pandemic emerged in Mexico last April, spreading first to the US and then across the Atlantic to Britain and Europe, it was thought that, as we were entering our summer, the virus might spread only slowly, giving us a few months grace to prepare for a winter surge.

It has not turned out that way. The expected winter surge, which may still occur, has been preceded by a summer one. In the early weeks of the pandemic, last May, Britain and Spain had roughly equivalent numbers of cases. But as the weeks have passed, Britain has been much harder hit. By 16 July, we had 9,718 confirmed cases and 14 deaths, nine times more than Spain with 1099 cases and two deaths. In Germany, France and Italy, the number of cases is still in the hundreds and there have been no recorded deaths.

Confronted with these puzzles, experts respond with a single phrase: the behaviour of the flu virus is very difficult to predict. Flu repeatedly confounds efforts to understand, and forecast, its course - it behaves in mysterious ways. Nevertheless, Sir Liam Donaldson, the Government’s chief medical officer, offered two possible explanations for Britain’s high rate of swine flu sickness this week.

Our close links with the US, with large numbers of visitors coming and going, made Britain an ideal staging post for the virus to break out from north America. Heathrow is one of the world’s busiest international transport hubs and as such is one of the key routes for global viral transmission.

In addition, Sir Liam said, disease surveillance in the UK is exceptionally good. It may be that we are picking up more cases which in other countries are going undetected.

A further reason, cited by some experts, is that schools close earlier for the summer holidays on the continent and this may have slowed the spread.

The upshot is that the pandemic in Britain may simply be more advanced than in other countries, and they will eventually catch up.

The unpredictability of the virus is re-inforced by its behaviour in the southern hemisphere, which was expected to face the first wave of the pandemic. But while there are significant epidemics in Australia, Chile and Argentina, there is little evidence of swine flu in South Africa, with just 18 confirmed cases at 6 July.

At the same date, Chile had 7,376 cases and 14 deaths while Argentina had 2,485 cases and 60 deaths.

Some parts of Australia have experienced significant outbreaks, but the overall total (5,298 cases at 6 July and 10 deaths) is still below that in the UK. And it is mid-winter there.

What will happen next? "It is very difficult to predict," said Allan Hay, the man in the best position to do so - were it possible - as director of the World Health Organisation’s Influenza Monitoring Centre in mill Hill, north London.

"In Mexico it peaked in late April, and it is supposedly turning down in the US. It certainly hasn’t been escalating in those countries, but nor has it disappeared."

"In the UK, we anticipate it might peak in a week or two - the closure of schools for the summer holidays may have an impact. Then we will expect to have a normal flu season in the winter and all the indications are that it will be caused by the pandemic H1N1 virus."

"We don’t know if it will replace the seasonal flu virus [or circulate in parallel with it]. In Australia, we have seen most infections caused by the pandemic virus. That is the usual experience - one virus tends to dominate. But we are monitoring the situation closely. Other seasonal viruses may return in the coming years."

It may be Britain’s misfortune to be hit first and hit hardest by the world’s first flu pandemic for 40 years. On the other hand, if it causes only mild illness this winter, we may be counting our blessings by the following one should the virus mutate to something nastier. What doesn’t kill us, makes us stronger.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments