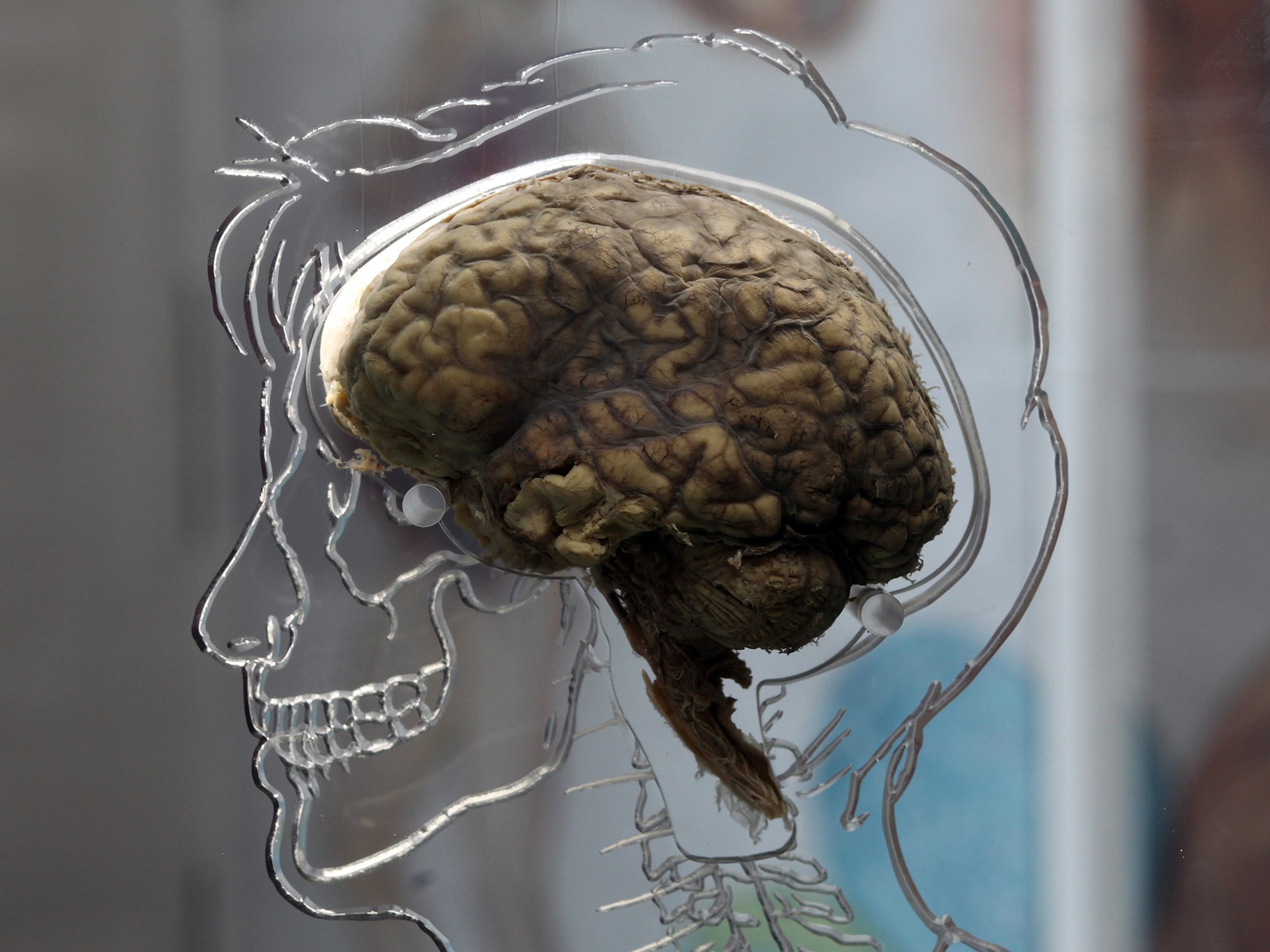

What is Cotard's syndrome? The rare mental illness which makes people think they are dead

Cotard's syndrome is "certainly rare", according to Mind

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A rare mental illness can make the sufferer believe they are dead, partly dead or do not exist.

Chronicled in the Washington Post by Meeri Kim, Cotard’s syndrome — sometimes dubbed ‘Walking Corpse syndrome' — is a condition where patients believe they are dead, parts of their body are dead or that they do not exist. Any evidence to support the fact they are alive is “explained away” by sufferers, according to the Post.

It is not classified under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) but is recognised as a “disease of human health” in the International Classification of Diseases. According to Mind: “It is linked with psychosis, clinical depression and schizophrenia”.

A spokeswoman for Mind told The Independent the syndrome was “certainly rare”.

“Cotard’s syndrome is a type of delusion that is usually associated with denial of self-existence," she said.

"The person experiencing the delusion might believe that they are dead, dying, parts of their body do not exist or they do not need to do activities to keep themselves alive (drink, eat, basic hygiene etc.)”

French neurologist Jules Cotard identified the first case in the 1800s. He described a woman suffering from the condition as affirming “she has no brain, no nerves, no chest, no stomach, no intestines… only skin and bones of a decomposing body”.

Esmé Weijun Wang spoke to the Post about her experience of the condition, which she suffered from for two months, explaining that after weeks of losing “her sense of reality” she woke up and told her husband she had actually died a month before, when she had fainted on a plane.

She said: “I was convinced that I had died on that flight and I was in the afterlife and hadn’t realised it until that moment."

Ms Wang, who was previously diagnosed with a form of bipolar-type schizoaffective disorder, later recovered and “no longer saw herself as a rotting corpse”.

A Mind spokesperson said “in terms of prevalence, there seems to be very few studies” meaning it is difficult to assess how many people are affected by the condition.

The Washington Post says “what causes Cotard’s syndrome and other delusions is a matter of debate” and speculates on a range of possibilities including brain impairment.

Professor and clinical psychologist Peter Kinderman told The Independent: "This syndrome is extremely rare so there's not much known about it, most literature on it is individual case studies over many years."

He says one theory about the condition's cause is that when "conditions exist to make someone feel confused or distressed" the individual can combine all their thoughts and beliefs - some of which may be distressing and unusual, with the feeling that they don't recognise themselves.

He said this could mean "people come up with the best conclusion they can to explain the experiences they're having, which may be that they're dead."

In 2013, a British man called Graham was interviewed in the New Scientist. He was diagnosed with Cotard’s syndrome after believing his “brain was dead”. He believed he had killed it after a suicide attempt following severe depression.

Graham said he visited a graveyard during this time as “it was the closest I could get to death”.

He said: “I didn’t need to eat, or speak, or do anything.”

Graham’s condition gradually improved with psychotherapy and drug treatment.