Pioneering first gene therapy trial opens the door for reversing some previously incurable forms of blindness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The sight of thousands of people with previously incurable forms of blindness could be saved thanks to a pioneering new gene therapy that requires just one operation.

In what scientists called a “very promising” first trial, six patients have been successfully treated for choroideremia – an inherited disease that leads to a gradual loss of sight and eventually total blindness.

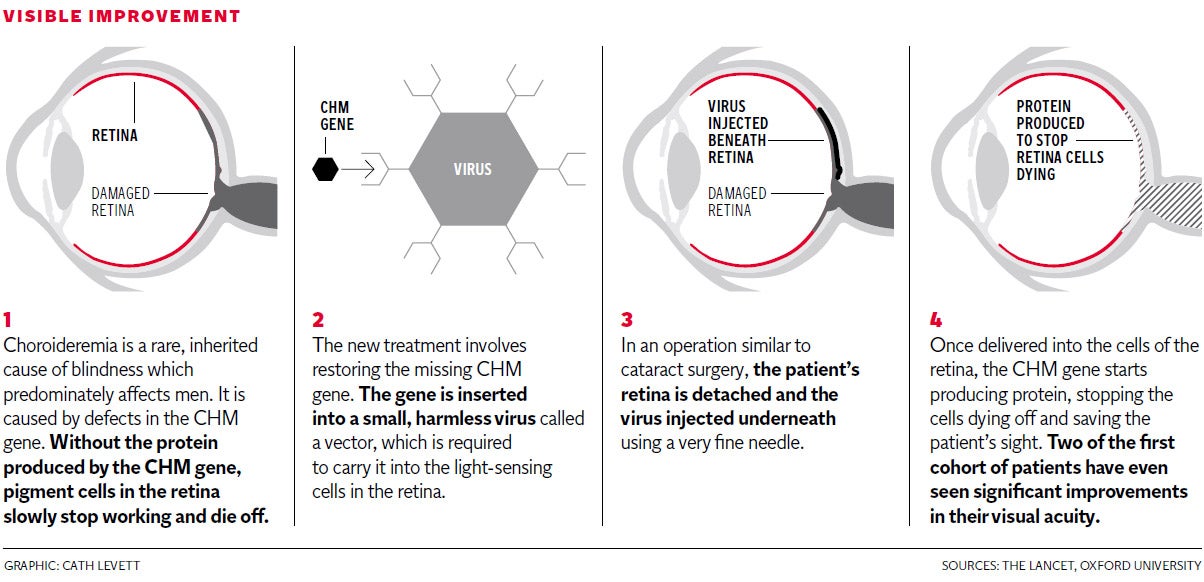

Click image above to enlarge graphic

While the condition itself is rare, the success of the new treatment holds out the hope that similar methods could be used to halt the progress of other genetic causes of blindness – including age-related macular degeneration, the most common cause, which affects 500,000 people in the UK alone.

The treatment, carried out by scientists led by the University of Oxford’s Professor Robert MacLaren, halts the damage done by choroideremia by restoring a defective gene in the retina.

In sufferers, a lack of proteins produced by the defective CHM gene leads light-sensitive cells in the retina to slowly top working, and eventually die off. The disease is often diagnosed in childhood or young adulthood. As it progresses the surviving retina gradually shrinks in size, reducing vision.

However, Professor MacLaren and his team have found a way of restoring a functional CHM gene to the eye, by transporting it in the cell of a harmless virus, which is injected underneath the retina with a very fine needle.

The gene then produces the necessary protein – REP1 – repairing the remaining light-sensitive cells and halting the shrinking of the retina.

Of the six patients to receive the treatment, all of them aged 35 to 63, two have reported improvements in their vision and the other four have reported no further loss of vision. Professor MacLaren said that while it was too early to say for certain if the gene therapy would last “indefinitely”, improvements had been maintained for two years in the case of one patient. A new cohort of three patients has now been treated, receiving a higher dose of CHM to see if the impact can be improved upon.

“The results showing improvement in vision in the first six patients confirm that the virus can deliver its DNA payload without causing significant damage to the retina,” Professor MacLaren said. “This has huge implications for anyone with a genetic retinal disease such as age-related macular degeneration or retinitis pigmentosa, because it has for the first time shown that gene therapy can be applied safely before the onset of vision of loss.”

“We’re riding on the back of the genetic revolution,” he added. “We now understand the genes involved in the disease. Having identified them, we’re now looking at ways in which we might treat them.”

Choroideremia affects one in every 50,000 people. The initial study, funded by the Department of Health and the Wellcome Trust, was chiefly focused on proving the safety of the technique, and follows research by Professor Miguel Seabra and others at Imperial College London into the causes of choroideremia, which was funded by the Fight for Sight charity.

The trial’s success means that a second phase trial could be carried out within a year. Professor MacLaren said that, if successful in later trials and passed by regulators, the technique could be available widely within three to five years.

Toby Stroh, 56, a solicitor from London, who had the operation in February 2012, said he had noticed “a marked improvement” in his vision, enabling him to read more of the letters on a sight chart. More importantly it has given him hope that his condition will not ultimately rob him of his sight.

“I have been living under this cloud for many years and been concerned I’m going blind,” he said. “I have said for a long time that as long as I can read and play tennis, I’ll be happy. As a result of this trial there is now a chance I’ll be able to do both these things for longer.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments