Thousands of dying non-cancer patients missing out on specialist end-of-life care, says report

The report added that people aged over 85, black, Asian and minority ethnic people are also more likely to miss out on vital care and pain relief

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Thousands of dying patients with conditions other than cancer are “unfairly” missing out on specialist end-of-life care, according to a major new report.

Urging a “major overhaul” of the way palliative care is delivered in the UK, experts from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) said part of the problem was that services had “traditionally” been geared towards people with cancer, with a lack of care options for the majority of people who die from other conditions every year.

People aged over 85, black, Asian and minority ethnic people and people living in poorer areas are also more likely to miss out on vital care and pain relief, or to be given the option to die at home or in a hospice.

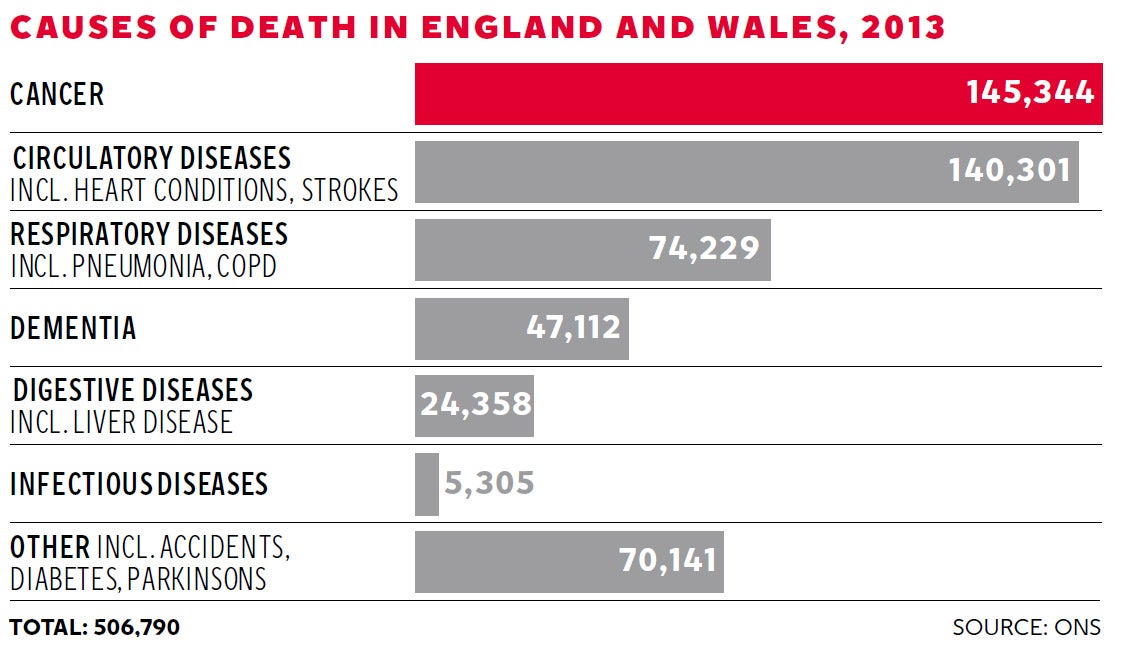

Between them, heart disease, respiratory illness and dementia account for considerably more deaths per year than cancer, but only 20 per cent of referrals for palliative care were for non-cancer conditions in 2013, the report said.

People with conditions other than cancer are also less likely to receive general care services. A survey carried out in three London areas between 2006 and 2011 found that cancer patients received on average 11.4 GP visits in their last three months of life, compared to 3.9 visits for people with other diagnoses.

Patients seriously ill with a heart condition or respiratory illnesses are likely to have a “less predictable” disease trajectory making it more difficult to plan their care in the final years of life, the report added. But experts said more needed to be done for all patients, regardless of condition.

“Everyone affected by a terminal illness should have access to all the care and support they need, regardless of their personal circumstances,” said Dr Jane Collins, chief executive of Marie Curie.

“This report shows that this is not the case and some groups are getting a worse deal than others.”

The need for palliative care is fast-increasing as the population ages.

Currently more than one in three deaths each year occurs among the over 85s. However, only 16 per cent of specialist palliative care is delivered to this age group.

Based on calculations from the 2011 Palliative Care Funding Review, the LSE report estimated that 92,000 people in England who would benefit from specialist end-of-life care were not getting it, as well as 11,000 people in Scotland and 6,200 in Wales.

“Part of the problem is that palliative care has traditionally been for people with cancer and there is currently a lack of suitable models of palliative care for people with non-cancer and increasingly complex conditions,” said the report’s lead author, Josie Dixon, of LSE’s Personal Social Services Research Unit.

There are also concerns that too many people are dying in hospital, rather than in their home, in a nursing home, or in a hospice.

MPs on the House of Commons Health Select Committee last month recommended the next Government should provide free social care for all dying people to ensure they could end their lives at home if they choose to.

The LSE report said that extending specialist palliative care services could actually lead to savings for the NHS and the care system, by avoiding expensive hospital stays. The report estimated net savings of £57.5m in England, £6.7m in Scotland and £3.9m in Wales.

Gus Baldwin, head of public affairs at Macmillan Cancer Support, said all patients should be allowed “choice at the end of life”

“We know that the majority of people at the end of life would prefer to die at home. Free social care could play a major role in enabling that to happen,” he said.

Claire Henry, chief executive of the National Council for Palliative Care said: “This report highlights serious inequalities in access to palliative care. We only have one chance to get care right for people who are dying, and it is unacceptable that a person’s background or diagnosis can be a barrier to receiving the care that they need.

“Everyone has a right to high quality palliative and end of life care, be it in a hospital, a hospice, a care home or their own home.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments