The tipping point? Half of people now survive cancer diagnosis

New research shows, for the first time, half of patients live for at least 10 years after diagnosis

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Half of all people diagnosed with cancer in England and Wales today will survive the disease, Britain’s leading research charity has said, in a landmark announcement which experts have hailed as a “tipping point” in the global fight against cancer.

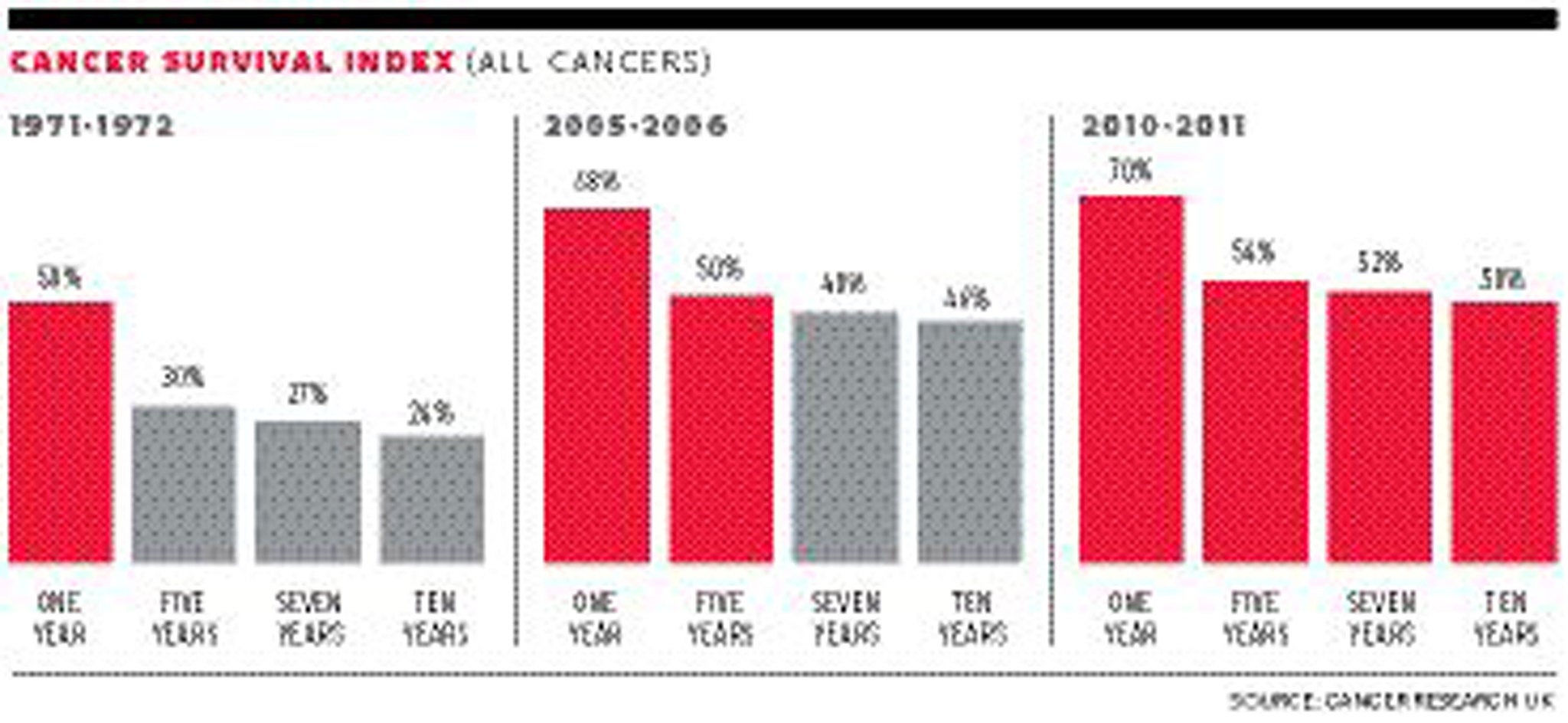

Using the largest and most up-to-date set of statistics on cancer treatment and survival available anywhere in the world, Cancer Research UK have been able to estimate that 50 per cent of patients who were diagnosed in 2010-11 will survive for 10 years – effectively meaning that they have been cured.who

Announcing their findings, which are derived from an analysis of survival trends involving more than seven million cancer patients diagnosed between 1971 and 2011 in England and Wales, Cancer Research UK said that by the 2030s, it was realistic to hope that as many as three in every four cancer patients would survive 10 years after diagnosis.

In the 1970s, the 10-year survival rate was as low as one in four, but a combination of improved therapies and drugs, earlier diagnosis and a reduction in the smoking rate have contributed to huge improvements in outcomes, with some types of cancer now nearing 100 per cent survival.

Dr Harpal Kumar, the charity’s chief executive, said that the past 20 years had seen an “explosion” in our understanding of the disease.

“We know more about cancer than we ever have before…the knowledge that we have gained in the past 20 years puts us in a fantastic position, not just to continue the progress we’ve made, but to accelerate it…” he said. “In 20 years’ time, we want three quarters of the people who hear those words: ‘you’ve got cancer’, to also hear the words: ‘but don’t worry you’ll be fine’. We firmly believe that’s achievable.”

Survival rates for nearly all cancers are improving every year. In the past 40 years, the 10-year survival rate for breast cancer has increased from 40 per cent to 78 per cent; for malignant melanoma from 46 to 89 per cent; and for testicular cancer from 69 to 98 per cent, according to research carried out for the charity by a team working under Professor Michel Coleman at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

However, the prospects for other types of cancer – in particular pancreatic and lung cancer – remain poor around the world. Survival rates in England and Wales, along with the rest of the UK, lag behind comparable countries in western Europe – largely because of delays in diagnosis of hard-to-spot cancers.

Dr Kumar said that, while the 50 per cent statistic was a major milestone, there was “a huge amount” of work still to do.

“We don’t want to celebrate the fact that only 50 per cent of patients are surviving their cancer,” he said. “In the UK that means around 160,000 people a year still don’t survive for 10 years or more, and across the world around eight million people.”

The charity is seeking to increase its £350 million annual spend on cancer research by 50 per cent over the next five to 10 years, Dr Kumar said. Research will particularly target new means of diagnosing and treating those cancers with stubbornly low survival rates. Pancreatic cancer has a 10-year survival rate of just one per cent, and is the only cancer for which death rates are still rising in Europe for both men and women.

And despite dramatic falls in the number of smokers since the 1970s, lung cancer death rates are still rising among women and for all patients 10-year survival is only five per cent.

But prospects for ever-improving survival rates, even in the most hard-to-treat cancers, were given a major boost earlier this month as Cancer Research UK announced a ground-breaking drug trial which aims to identify “personalised” cancer drugs for lung cancers. The trial, the first of its kind, builds on the “genetic revolution” in cancer science, and a new understanding of the extent to which the genetic makeup of different people’s cancer tumours can vary, requiring a broader range of more targeted drug treatments.

“As little as 20 years ago people were talking about a single magic bullet for cancer,” Dr Kumar said. “This notion that there would be one type of treatment that would be beneficial across all types of cancer [has been] put to bed, that isn’t ever going to be the case.”

Professor Coleman said that 10-year survival in the vast majority of cases meant that the disease had been beaten.

“As a whole the patients who survive that long no longer have any different chances of surviving than the rest of the population,” he said.

“The idea of cancer as a death sentence is gradually evaporating in this country, thank goodness,” he added. “It is still considered a death sentence in many countries around the world, to the extent that people given a diagnosis will not seek treatment because they accept with fatalism that they are going to die… that is the kind of perception, the kind of myth… that data like this can counter.”

Late diagnosis was among the key reasons for poor survival rates in some cancers, he said, particularly those for which symptoms are non-specific, such as persistent cough in the case of lung cancer, a sore throat for oesophageal cancer, or a headache for brain tumours.

Delays in patients visiting their GP, in GPs diagnosing cancers and in referrals to treatment have all been identified as causes for the UK’s comparatively poor performance on cancer. However Professor Coleman said it was wrong to solely blame GPs who he said were seeing between six and eight cases of cancer out of thousands of patient contacts every year.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments