The sisters-in-law who both faced cancer – one still here, the other gone

Story inspires their TV director husband and brother to make a film to 'de-mystify' the disease

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Behind a landmark Channel 4 documentary showing cancer treatment breakthroughs by British hospitals is a personal heartbreak which inspired a Bafta-winning film-maker to attempt to "demystify" the disease.

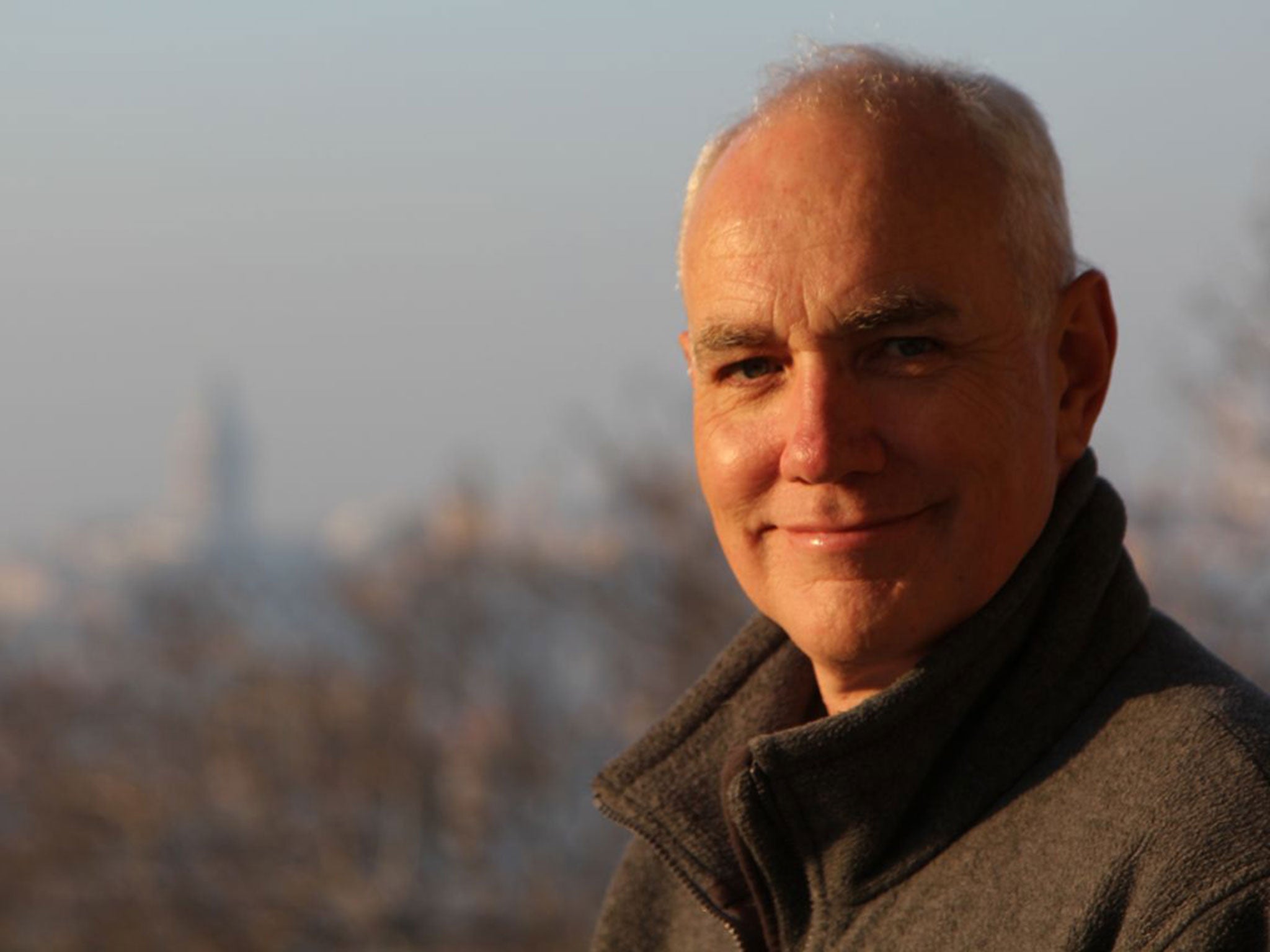

Brian Woods has been given unprecedented access to the latest drug trials being conducted at University College London's Cancer Institute and University College Hospital's Macmillan Cancer Centre in treating conditions including sarcoma, lymphoma and prostate cancer.

For the past 14 years, Woods has supported his wife Debs, also a film-maker, as she has been successively diagnosed with tumours in her breast, bones and her brain, but survived with the help of the Royal Marsden Hospital in London. In that same time, he lost his sister, Gill Edwards, a successful author, who chose to reject all conventional treatments as she fought her own breast cancer with alternative medicine.

"I want to demystify cancer and I want people to realise they should live for today, no matter how old they are," said Woods. "I also want people to understand why it is important... to take part in cancer trials – that's the only way science moves on, when people say: 'You can experiment on me.'"

In 2000, Debs was diagnosed with a tumour in her breast; the tumour was removed at London's Charing Cross Hospital, but she elected not to have follow-up radiotherapy. "In retrospect, it was probably a mistake. Radiotherapy mops up the odd cancer cells," said Woods. "We certainly would have made a different decision with the benefit of hindsight."

Three years later, at a routine follow-up, Debs was bluntly informed by a registrar: "We've crossed a Rubicon –the results are positive." Her cancer was metastatic – meaning it had spread around the body – and had re-established itself in her rib bones. "It felt like a death sentence," said her husband.

She transferred to the Royal Marsden to start monoclonal antibody treatment. Her oncologist was open to her embracing complementary medicine, such as food supplements. After reading Your Life in Your Hands by Jane Plant, a scientist and breast cancer victim, the couple changed to a non-dairy diet. The cancer seemed under control.

Gill, meanwhile, had always favoured a more radical approach to medicine. A successful author of self-help books including Living Magically, she espoused the philosophy that "we create our own reality", said Woods, who has made a succession of award-winning films, many of them, such as The Dying Rooms and Zimbabwe's Forgotten Children, exposing injustices against children around the world.

In 2009, she contacted her brother. "She said she had found a lump in her breast and determined that it was breast cancer. It was important to her that she dealt with it in a way that felt right to her," he recalled.

"She didn't wish to discuss it with people who had chosen allopathic or conventional Western medicine. We had been down this path for eight years, and amazingly she thought we had nothing to say that might help."

Gill believed Western medicine "was toxic and would be damaging", preferring to rely on natural treatments, such as a juice-based Gerson diet and Essiac, a herbal remedy for cancer. A few months later, she reported that the lump had gone. "We were delighted," said Woods.

The next year, as Debs was working on the edit of a film about young rape victims for Channel 4's Dispatches, called The Lost Girls of South Africa, she suddenly felt exceptionally tired. A health check revealed a brain tumour. Surgeons operated on her that week and this time she had radiotherapy to remove any other cancerous cells. By the end of the week, she was back home again. "It was an extraordinary five days," said her husband.

Meanwhile, Gill's cancer returned. The tumour was in her left breast above her heart and she believed it was the result of a traumatic love affair. "She felt the emotional turmoil around that relationship had brought back the cancer," said Woods.

In vain, he attempted to convince his sister that modern science was not incompatible with her beliefs. She died in 2011 at the age of 55.

As a devoted brother, he remains angry that she did not heed his advice and made what she believed was her choice to die. "It was a brave decision, but I think it was also a reckless decision because she had a teenage son and two brothers and a mum and dad who loved her, who I feel she let down by dying."

After her death, Brian posted the sad news on her website. "Within days, there were hundreds of comments from people all over the world saying she had changed their lives," he said. "She was a successful and popular author and touched many people's lives very positively."

Debs, meanwhile, is well and happy. There have been a couple more metastases, in her femur and pelvis, but each one was treated. She is, like many others, getting on with her life living with cancer.

It was the contrasting outcomes for Gill and Debs that made Woods want to make the film. "I completely embrace complementary treatment that supports conventional medicine, but based on our experience I would advise anyone against relying solely on alternative therapies," he said.

Cancer on Trial takes an educational approach to a disease that will kill one in four of the UK population. The Wellcome Trust paid for expensive computer graphics showing how the latest treatments can impact on tumours. The film shows Debra Cox undergoing cutting-edge microwave ablation treatment for sarcoma. Dennis Hadley agrees to take an experimental drug as a last chance for treating his lymphoma, and the impact on his tumour astounds even Rakesh Popat, who conducts the trial.

Above all, Woods wants people to think about what matters most to them and to use their time wisely. "It's carpe diem– it's seize the moment. Those bumper-sticker phrases – they're right!" he said.

"After my sister died, there were bottles of champagne she had been keeping for a special occasion and unopened bottles of perfume she had been keeping for a special occasion. Every day is a special occasion – that's how you deal with cancer."

'Cancer on Trial' will be shown on Channel 4 on 16 October as part of the Stand Up to Cancer season

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments