Tests begin on 'traffic light pacemaker' that could revolutionise heart treatment

Could stem cell-generated heart cells be implanted to regenerate damaged areas?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

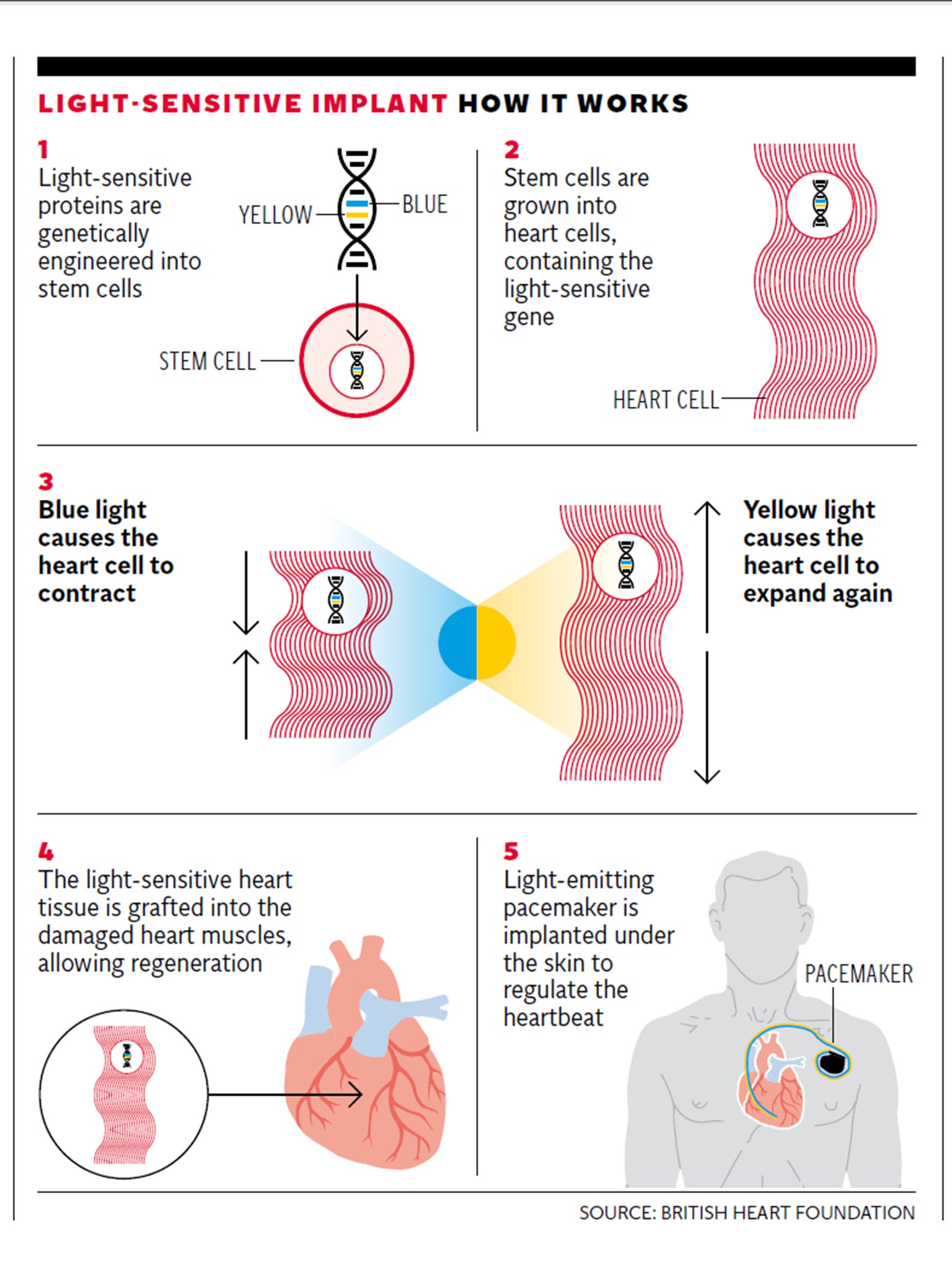

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists are to begin work on a revolutionary “traffic light pacemaker” that controls the beating of damaged hearts using blue and yellow fibre optic lights inside the body.

Heart attacks and other major cardiac problems can damage the heart muscle, leaving patients vulnerable to dangerous disruptions in the heart’s rhythm – known as arrhythmia – often leading to heart failure.

Researchers are exploring whether stem cell-generated heart cells could be implanted to regenerate the damaged areas. But progress has been held back because tests in the laboratory and in a small number of patients have shown that new tissue often fails to beat in time with the remaining healthy heart muscle.

Now, a joint UK-Israeli project funded by the British Heart Foundation (BHF) and the British Council’s Britain Israel Research and Academic Exchange (Birax) are to develop the use of special proteins that react to light to regulate the heartbeat.

Professor Chris Denning, of the University of Nottingham, who will lead the UK part of the project, said: “These light-sensitive proteins are not novel – good old Nature has been using these things for a long time. Like those in the back of the eye, they receive a light signal that converts into an electrical signal.

“In the eye, that signal goes to the brain enabling you to see. In green algae it allows the organism to move toward a light source and thrive. All we are doing in this project is hijacking some of that natural technology and putting it into heart cells so that hearts become sensitive to light.”

Blue light emitted by the pacemaker, which will shine on the implanted tissue through fibre optic wires, will react with one of the proteins to induce electrical activity that will make the new muscle contract.

Yellow light will have the opposite effect, reacting with other protein to suppress electrical signals and prevent contraction. Applied in sequence, these lights make the muscle mimic a natural heartbeat.

An electronic device will monitor the natural rhythm of the remaining healthy heart muscle and relay it back to the pacemaker, ensuring the lights shine in sync with the natural heartbeat.

The three-year project, which will be funded by a £400,000 grant from the BHF and Birax, will assess the tissue grafts in rats and then, if successful, in pigs.

If results are positive the devices could be tested on humans within five years. Research will be carried out at the University of Nottingham and the Israel Institute of Technology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments