Sale of human organs should be legalised, say surgeons

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

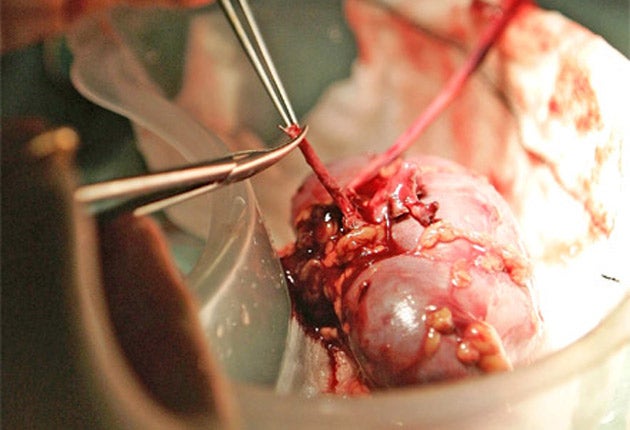

Leading surgeons are calling for the Government to consider the merits of a legalised market in organs for transplant. A public discussion on allowing people to sell their organs would, the doctors say, allow a better-informed decision on a matter of such moral and medical significance.

At stake are the lives of thousands of people who may die before a suitable donor can be found. Eight thousand people are on the transplant waiting list, more than 500 of whom die each year before they obtain an organ, and the numbers are rising by 8 per cent a year.

But there are serious concerns that introducing payments for people who donate their organs would result in poor and vulnerable people coming under severe pressure to alleviate their financial problems by selling a part of their body.

Professor Nadey Hakim, a Harley Street surgeon, and one of the world's leading transplant surgeons, believes that a properly regulated market should be permitted so that the black market in organs is, if not destroyed, at least dramatically reduced.

He sees the effects of the black market in patients so desperate to have a transplant operation that they travel abroad for an organ.

This "transplant tourism", he said, often results in botched operations requiring further surgery when the patient returns to Britain. It would make better sense for organ sales to be allowed in the UK under a strictly regulated regime, he said, adding: "Let's have a system that doesn't allow organs with HIV or whatever."

Professor John Harris, an ethicist at the University of Manchester, believes a debate and the introduction of an organ market are long overdue. "Morality demands it," he said. "It's time to consider it because this country, to its eternal shame, has allowed a completely unnecessary shortage for 30 years. Thousands of people die each year [internationally] for want of organs. That's the measure of the urgency of the problem.

"Being paid doesn't nullify altruism – doctors aren't less caring because they are paid. With the current system, everyone gets paid except for the donor."

Professor Harris has developed proposals for an ethical market in organs in which donors would be paid as part of a regulated system. Such a system, he said, would have to be controlled within a strictly defined community, probably the UK but possibly extended to the EU, so every organ could be accounted for. No imports would be allowed. The NHS would be the sole supplier and would distribute organs as it does other treatments – ability to pay would not be a factor. Consent would be required for every donation and would have to be rigorously carried out to ensure no donor was subjected to untoward pressure.

Professor Sir Peter Bell, former vice-president of the Royal College of Surgeons but now retired from practice, wants a public debate because there is such a shortage of organs for transplantation: "It is time to debate it again. There is a great shortage of organs."

Recent medical advances, he said, now make it reasonable to allow a kidney market and perhaps the sale of liver donations, although other body parts remain too risky, he argued.

"If someone wants to alleviate a financial problem why shouldn't he do that? It's his choice," he said.

Professor Bell suggested a fee of £50,000 to £100,000 for each kidney, the equivalent of one or two years on dialysis, and added: "Kidney donation has now become so safe it's something you could ethically justify and it would stop all this illegal trafficking."

There remains stiff opposition to liberalising the market, not least from the British Transplantation Society (BTS). Opponents agree there should be a public debate about the merits and flaws of a market in organs. "The British Transplantation Society opposes this view, however it is prepared to debate this issue as the theoretical and empirical literature evolves," said a spokesman.

Keith Rigg, the transplant surgeon and BTS president, said: "I'm happy to debate it. There are pros and cons. I think the trouble is it would require a huge change in public opinion and legislation. One argument against a regulated market is if you are paying some people, what would be the impact on the existing deceased donor programme and living donor programme?"

Mr Rigg pointed out that in the last two years there has been a steep rise in donations, especially from live donors which have now overtaken deceased donors in number. There were 1,058 live donations in the last year compared to 959 from dead patients. With an average of 2.75 organs from each donor, surgeons were able to carry out 3,700 transplants in the last year. Mr Rigg fears that introducing a regulated organ market would attract paid donors at the expense of voluntary donors.

Other opponents to the creation of a market in organs say it would cross major ethical barriers – and there are less radical measures that could be looked at first. "I don't believe we should be commercialising parts of our bodies," said Professor Anthony Warrens, Dean of Education at The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, adding that "the most disadvantaged" people would end up selling parts of their bodies, potentially with disregard for the risks involved. "It's just very risky if it's legalised," said Kenneth Boyd, professor of medical ethics at the University of Edinburgh.

A radical extension to the organ transplant programme is being launched by the Government, bringing fresh hope to hundreds of desperately ill patients. In a boost to the existing programme, hospitals will retrieve organs from patients who die in accident and emergency departments – as well as from those who die in intensive care units, as is currently the case. The move is expected to make hundreds more organs available to reduce the waiting list.

Figures show that 28 per cent of the population has signed up to the organ donor register, but only 1 per cent die in circumstances where their organs can be used. A&E departments lack the equipment and trained staff for the task.

Should we be allowed to sell our organs?

Yes

* It would boost the supply of organs helping to solve the national shortage

* It would end the existing black market in organs, making it safer for people to donate

* It would mean donors were paid like everyone else – doctors, nurses, transplant co-ordinators – involved in transplantation.

No

* Encouraging people to sell parts of their bodies is morally wrong and would almost certainly lead to exploitation of the poor.

* Potential donors would be more likely to conceal conditions or illnesses that might rule them out.

* It would undermine the existing altruistic donor programme.

Organ transplants in numbers

2,017 Number of donors in the UK last year, of whom 1,058 were alive, and 959 were dead

3,698 Total number of organs transplanted last year, excluding corneas

1,482 Number of kidneys transplanted last year from deceased donors. 1,038 came from living donors

17.7m Number of people on the organ donor register

7,892 Total number of people waiting for a transplant. Of those, 6,741 are waiting for a kidney

1,000+ Number of people waiting for an organ transplant who will die before one becomes available

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments