'Personalised' cancer vaccine moves a step closer

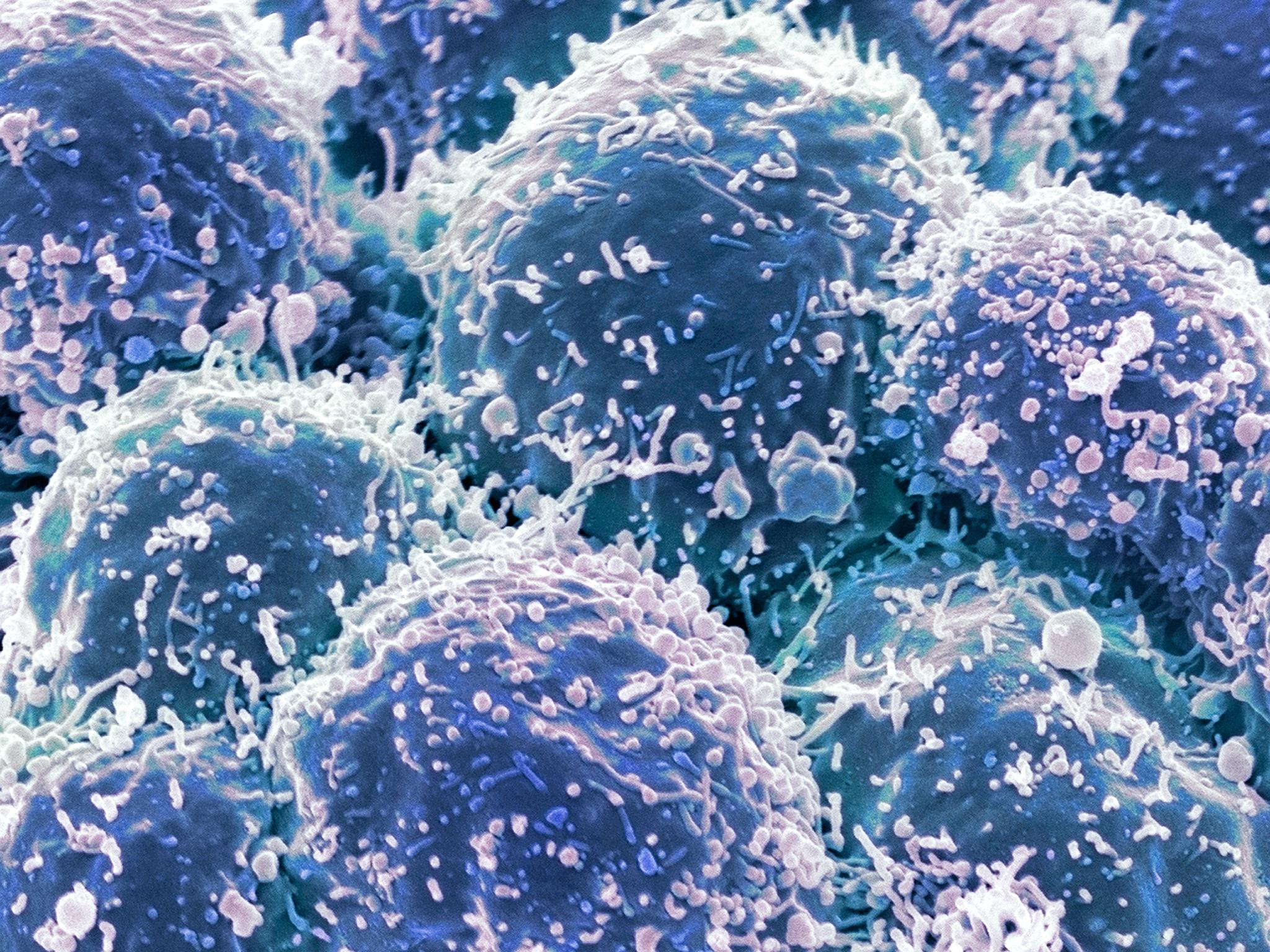

The therapeutic vaccine stimulates the immune system to attack cancer cells

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A cancer vaccine that is tailor-made to work on individual patients has come a step closer following a study showing that a prototype injection causes the complete control of aggressive tumours in laboratory mice.

The therapeutic vaccine works by stimulating the body’s own immune system to identify and attack cancer cells while leaving healthy tissue unharmed.

Scientists said that it could be a blueprint for “personalised” cancer vaccines targeted against the specific tumour cells of each individual patient and that they have already begun early clinical trials on seven patients suffering from skin cancer.

The study on mice with skin, breast and colon cancer showed that injecting strands of “messenger” RNA – a genetic molecule similar to DNA – can stimulate the animals’ immune T-cells to seek out and destroy aggressive tumours.

The research is part of a wider body of work into cancer immunotherapy, which aims to find ways of recruiting the powerful immune defences of the body to recognise and eliminate cancerous cells before they have spread fatally to vital organs and tissues.

The latest study is being heralded as an important step towards developing a manufacturing method that can produce cheap and effective cancer vaccines to order for individual patients who possess unique combinations of proteins on the surface of their tumour cells that the vaccine can recognise.

“This is extremely exciting scientifically and conceptually because this could be the future of personalised medicine and we’re already in clinical testing with results expected later this year,” said Ugur Sahin of the Johannes Gutenburg University in Mainz, Germany who led the study published in the journal Nature.

“This novel insight indicates that most human cancers may be eligible for successful cancer immunotherapy. However, every patient’s tumour possesses a unique set of mutations that must first be identified, which means that targeted vaccine approaches need to be individually tailored,” said Dr Sahin, who is also the co-founder and chief executive of BioNTech, a biotech company that has pioneered the approach.

“Our aim is to make truly personalised cancer immunotherapies affordable and broadly available,” he said.

The researchers generated vaccines based on synthetic strands of mRNA designed to match the particular proteins or “epitopes” on the surface of the mouse’s tumour cells. The mRNA molecules encouraged the T-cells to attack these target mutations on the tumours, leading to improved survival of the mice compared to untreated controls.

The study found that it was possible to generate a strong immune response by generating mRNA vaccines that could recognise several epitope proteins – called polytopes – that stick out from the surface of the targeted tumour cells, the scientists said.

“We show that vaccination with such polytope mRNA vaccines induces potent tumour control and complete rejection of established aggressively growing tumours in mice,” they said.

Professor Kevin Harrington of the Institute of Cancer Research in London, who was not involved in the study, said the findings are important. “This study in mice provides the first evidence that we may be on the threshold of being able to produce individualised vaccines directed against specific mutations present in a patient's tumour,” Professor Harrington said.

"This paper provides the first evidence of a significant anti-tumour effect with such a technique, suggesting that it may be possible to direct the immune system to fight cancer using personalised RNA vaccines. If results are similarly encouraging in human trials, this will help to accelerate the development of combination immunotherapy treatments using the antibody therapies already in the clinic, together with vaccines targeting the mutations present in individual cancers.”

“Rapid production of purpose-built vaccines appears to be possible and can now be tested in carefully designed clinical trials. As yet, this approach must be seen as experimental but it potentially represents a new way of harnessing the power of the immune system against cancer,” he said.

Professor Peter Johnson of the Cancer Research UK Centre at Southampton General Hospital, said: “This [study] provides the first evidence of a significant anti-tumour effect with such a technique, suggesting that it may be possible to direct the immune system to fight cancer using personalised RNA vaccines. If results are similarly encouraging in human trials, this will help to accelerate the development of combination immunotherapy treatments using the antibody therapies already in the clinic, together with vaccines targeting the mutations present in individual cancers.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments