Nine out of ten male prostate cancer sufferers could be treated after 'game-changing' study

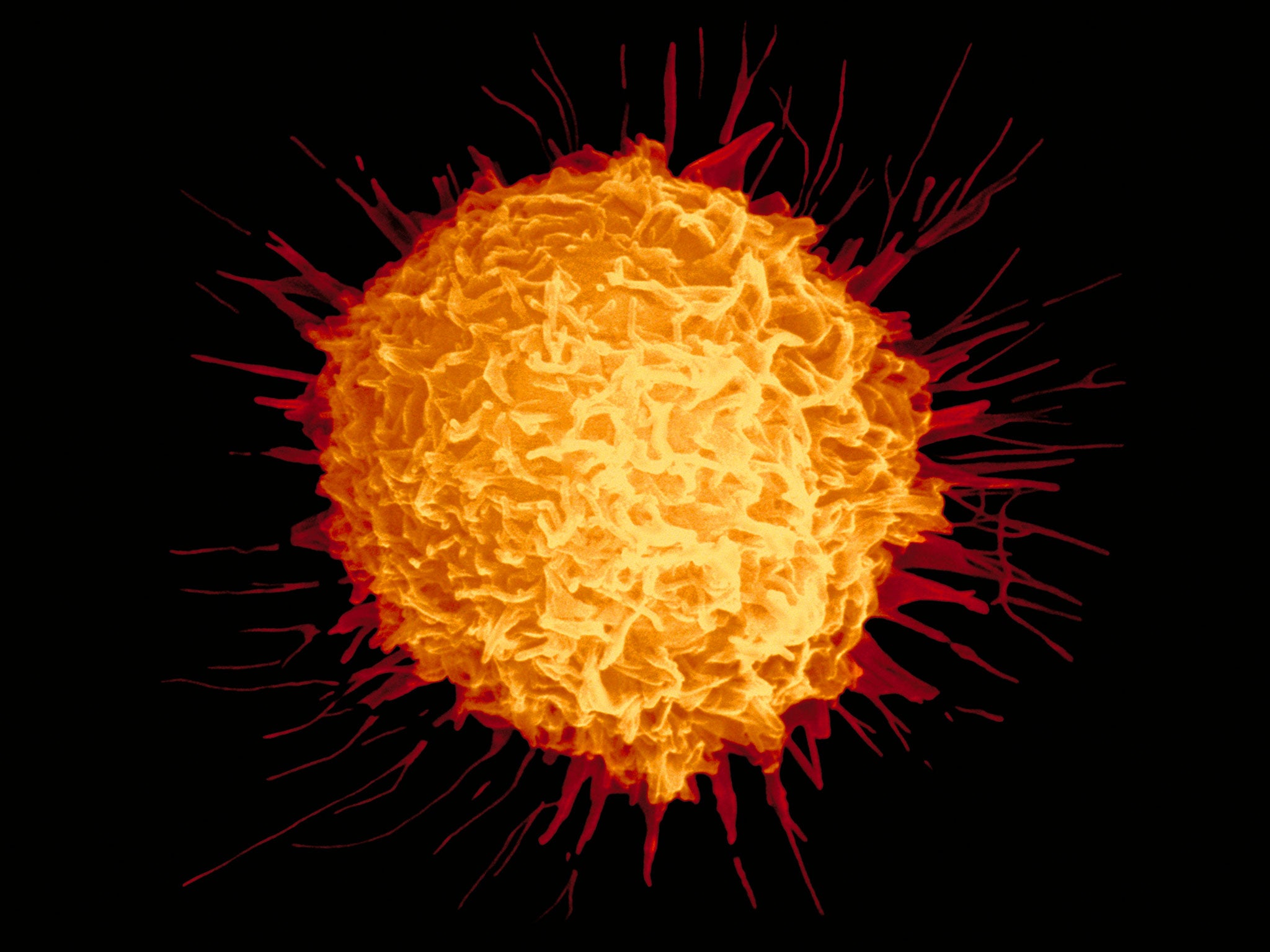

In what is being called the 'Rosetta Stone' of prostate research, scientists have identified the genetic mutations linked with the spread of prostate cancer

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Nine out of ten men with advanced prostate cancer – an incurable and fatal disease – could soon be treated with new or existing drugs following a pioneering study that scientists have called the “Rosetta Stone” of prostate research.

For the first time, researchers have identified the genetic mutations linked with the spread of prostate cancer around the body and have found that up to 90 per cent of them are potentially treatable, which could extend the lives of thousands of men with advanced disease.

“This is a game changer. It’s really going to alter the way we deal with this lethal disease. It’s as if we’ve taken a prism to the white light of advanced prostate cancer and produced a rainbow of colour,” said Professor Johann de Bono, one of the leaders of the large international collaboration that carried out the work.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer of men with more than 40,000 new cases diagnosed each year in the UK. Although it can be cured if caught in the early stages of the disease, once it spreads beyond the prostate it can only be managed with hormone-suppressing drugs and for a limited time.

Professor de Bono of the Royal Marsden Hospital and the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) in London compared the new research to the discovery of the famous Rosetta Stone that allowed historians to translate the meaning of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs by comparing them with the text of other known languages.

“We have for the first time produced a comprehensive genetic map of the mutations in prostate cancers that have spread around the body. This map will guide our future treatment and trials for this group of different lethal diseases,” Professor de Bono said.

“We’re describing this study as prostate cancer’s Rosetta Stone because of the ability it gives us to decode the complexity of the disease, and to translate the results into personalised treatment plans for patients,” he said.

The study, by a team of researchers from eight institutions in the US and Europe, analysed the DNA mutations that have occurred in the “metastatic” tumour cells as they spread beyond the prostate glands of 150 men with advanced disease. Nearly two thirds of them had developed mutations in a molecule that interacts with the male androgen hormone, which is targeted by current standard treatments – potentially opening up new avenues for hormone therapy, the scientists said.

Nearly 20 per cent of the patients had developed mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which are well known to play a critical role in the development of breast and ovarian cancers that are already targeted by existing drugs called the PARP inhibitors – suggesting that these could now be used to treat some forms of advanced prostate cancer.

Some of the newly discovered mutations were new to prostate cancer but have been seen in other forms of cancer where drugs are already in use. About 8 per cent of the patients had inherited mutations that put them at risk of developing prostate cancer, suggesting that men in at-risk families could in future receive genetic counselling.

The researchers, led by the ICR, also found that some mutations had occurred in genes that had not previously been liked with prostate cancer, probably because past research has concentrated on mutations of the primary tumour within the prostate gland, rather than the metastatic tumours that arise elsewhere in the body.

A key finding of the study, published in the journal Cell, is that prostate cancer is not one disease but several which are each determined by the type of DNA mutations that occur in the tumour cells as the disease progresses from one stage to another. This opens the door to treating each patient in a personalised manner based on the type of mutations they carry and the drugs to which they can be targeted.

“Our study shines new light on the genetic complexity of prostate cancer as it develops and spreads – revealing it to be not a single disease, but many diseases each driven by their own set of mutations,” Professor de Bono said.

“What’s hugely encouraging is that many of the key mutations we have identified are ones targeted by existing cancer drugs, meaning that we could be entering a new era of personalised cancer treatment,” he said.

Professor Paul Workman, president of the ICR, said: “This major new study opens up the black box of metastatic cancer, and has found inside a wealth of genetic information that I believe will change the way we think about and treat advanced disease…the findings could make a real difference to large numbers of patients.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments