Hope for the future as Malawi battles the Aids virus's capacity to infect succeeding generations

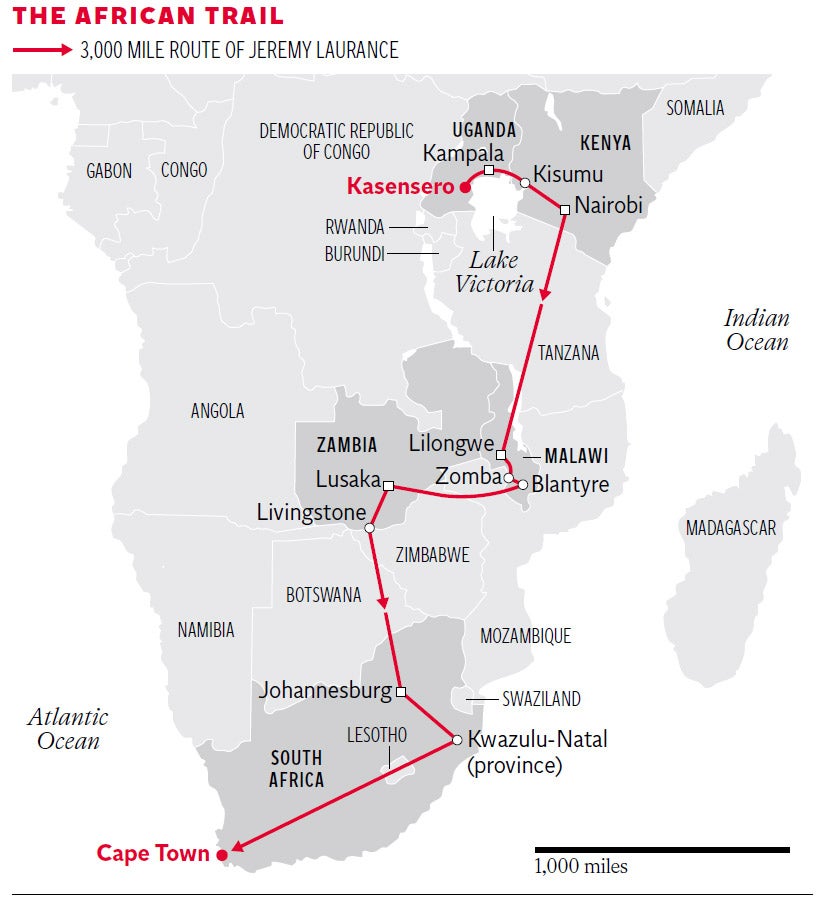

In the third part of his 3,000 mile journey through Africa’s Aids epidemic, Jeremy Laurance finds a tiny nation that is finding its own way to battle stigma and refusal of treatment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Day Three: Malawi

They serve coke, cake and gospel music on the 7am bus from Blantyre to Lilongwe in Malawi – and they ask for the name and telephone number of your next of kin before you board. With a chorus of “Jesus, how great thou art” ringing in my ears, I settled down for the five-hour journey with a copy of the Malawian newspaper The Nation – which carried a full page article on “labia stretching”, claimed by some to increase sexual pleasure.

In this deeply religious and conservative country, more than one-in-ten people are infected with HIV – almost twice the rate in Uganda and Kenya. In the antenatal clinic at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Blantyre 18 per cent of women are HIV positive.

Now this impoverished nation has found itself leading the world with a scheme to tackle one of the worst effects of the Aids virus – its capacity to infect succeeding generations. It has a devised a scheme to offer immediate, lifelong treatment with anti-retroviral drugs to all pregnant women who test positive for HIV.

The scheme is controversial because it involves prioritising pregnant women over other HIV positive adults who only qualify for treatment when they are sick. It has also run into an unexpected problem – high drop-out rates. This has raised fears it could fuel drug resistance.

More than 250,000 babies were born infected with HIV worldwide in 2012. Although the number has halved in the last decade, hundreds of thousands still suffer arrested development, face a lifetime on powerful drugs, and form a reservoir for the continued spread of the virus.

I saw its consequences at Zomba hospital, 300km south of Lilongwe, where one-in-seven of the population is HIV positive, the highest prevalence in the country.

David Saiti, 43, a vegetable seller, had brought his daughter, Elizabeth for treatment. The shock in my interpreter’s voice when he asked the little girl her age was obvious. “Ten,” she said – though she looked much younger. “I thought she was six,” he told me.

I asked Elizabeth what her favourite subject at school was. “Maths,” she answered quietly, adding “I want to be a doctor.” She has spent her life surrounded by them. But when I asked if she knew what was wrong with her, she hid her face in her shawl. Despite 30 years of effort to increase tolerance, the stigma of an HIV diagnosis remains.

Cutting the risk of transmission of the virus from mother to child has been possible for decades, initially with a single dose of an anti-retroviral drug. There have been many changes since in the regimen recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and today the risk can be reduced to below 5 per cent if the mother accepts long term treatment with anti-retroviral drugs.

That is a big if. For many women, making repeat visits to the clinic – often involving lengthy journeys – for tests of their immune system was too difficult. More importantly, it was beyond the capacity of Malawi’s rudimentary health system to provide. Instead, it adopted a public health approach: give anti-retroviral drugs immediately to all pregnant women who are found to be HIV positive, and continue them for life, without the requirement for repeat testing of their immune system.

The effect has been dramatic. Launched in July 2011, the scheme, known as Option B+, has reached 60,000 women, a six-fold increase in a year. The number of clinics distributing anti-retroviral drugs has more than doubled and doctors report significant falls in the number of HIV positive babies being born.

“The trend is definitely down,” said Neil Kennedy, head of paediatrics at Queen Elizabeth Hospital. “Option B+ is fantastic. It is the right answer.”

Other countries are following Malawi’s lead. Uganda adopted Option B+ six months ago, Zambia and Rwanda have similar plans and the scheme is being discussed in Zimbabwe and Tanzania.

“I was surprised how quickly it was taken up. It was unbelievably fast,” said Eric Schouten, formerly of the Ministry of Health and one of the architects of the scheme. “A small African country said to the WHO: ‘We don’t like your guidelines, they don’t make sense’ – and the world is following us.” WHO has since modified its stance to include the regimen.

The main challenge is persuading women who discover they are infected during routine antenatal tests to accept the treatment – and stick with it. Stigma remains a key barrier. “It is a real challenge for women to be told they are HIV positive and to take home the drugs and tell their family they are going to take these for the rest of their life. Many women leave the clinic and throw the drugs away. We never see them again,” said Fabian Cataldo, a researcher with Dignitas International in Zomba.

Breaking the news to their husbands is the hardest task. Official figures from the Malawi Aids Commission suggest around a quarter of women default. Others, such as Medicins Sans Frontiers, say the default rate is higher. “We found nine per cent dropped out on the first day and a further 27 per cent at three months,” said a spokesperson.

If the scheme led to a rise in drug resistance, the consequences could be devastating. The current standard drug cocktail – three anti-retrovirals in a single pill – costs $200 per person per year and is wholly funded by donors. Malawi could not afford expensive second line HIV drugs if the first line failed. “We are worried about resistance,” said Frank Chimbwandira, head of HIV at Malawi’s Ministry of Health.

To improve adherence, Dignitas has trained a team of “expert mothers”, women like Grace who have been diagnosed HIV positive and faced the loss of spouse and home and can counsel women enduring similar trauma.

Aged 39, she was diagnosed in 2007 while pregnant with her fifth child. It took her two weeks to tell her husband. “He left four months later. Now he is married again.”

Grace remarried in 2011, to a man who was also HIV positive. She said: “There is a lot more awareness of the importance of anti-retroviral drugs. There would be a different reaction now.”

Her optimism is encouraging. But less than half the clinics in the south east have expert mother support, and coverage is lower elsewhere.

The key to reducing stigma is to normalise HIV testing so that everyone knows their status and checks it on a regular basis. Malawi is pioneering a second innovation. It is the first country in Africa to introduce HIV self-testing at home. The scheme has been piloted among 16,000 people in Blantyre with an 84 per cent acceptance rate after a year and a three-fold increase in those reporting they have HIV and starting on treatment.

Professor Liz Corbett, leader of the study at the Malawi-Wellcome-Liverpool Research Centre in Blantyre, said there were fears that home testing would lead to marital disputes and even violence. “Nothing has been reported that is alarming in discovering this information in this way – it is very reassuring. The commonest complaint is from those in the control arm who want the test. There would be no problem getting people to test annually based on what we found. To maximise prevention we need people to test annually in areas of high HIV prevalence”

Fighting ignorance: A doctor’s story

In the intensive care unit at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Blantyre – Malawi’s second city – Laura Newberry, an American paediatrician, pointed to a two-month-old baby in a cot, its tiny chest pumping 90 times a minute as its mother, wearing a striped blue top and brushing the hair from her face, leaned anxiously over her child.

“The baby has pneumocystis pneumonia, a consequence of HIV infection,” said Dr Newberry.

“The mother discovered she was HIV positive late in pregnancy – too late to get treatment to protect her baby. I told her she must bring her husband for testing but she wants me to call him.

“That often happens. I have had five babies die because the mother refused to give them drugs. I am sure it is because of their husbands.

“They cannot risk disclosing that they are HIV positive because of the risk that he may leave them. They don’t want to lose him and they would rather put their health and that of their babies at risk.”

The writer’s trip was funded by a no-strings grant from the European Journalism Centre

Tomorrow: Male circumcision - the 'surgical vaccine' that is proving hard to sell - to women

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments