Teixobactin discovery: Scientists create first new antibiotic in 30 years - and say it could be the key to beating superbug resistance

Scientists have conducted tests that show teixobactin could provide a platform for new treatments to combat superbugs

A new antibiotic – the first in nearly 30 years – has been discovered by scientists who claim it appears to be as good, or even better, than many existing drugs with the potential to work against a broad range of fatal infections such as pneumonia and tuberculosis.

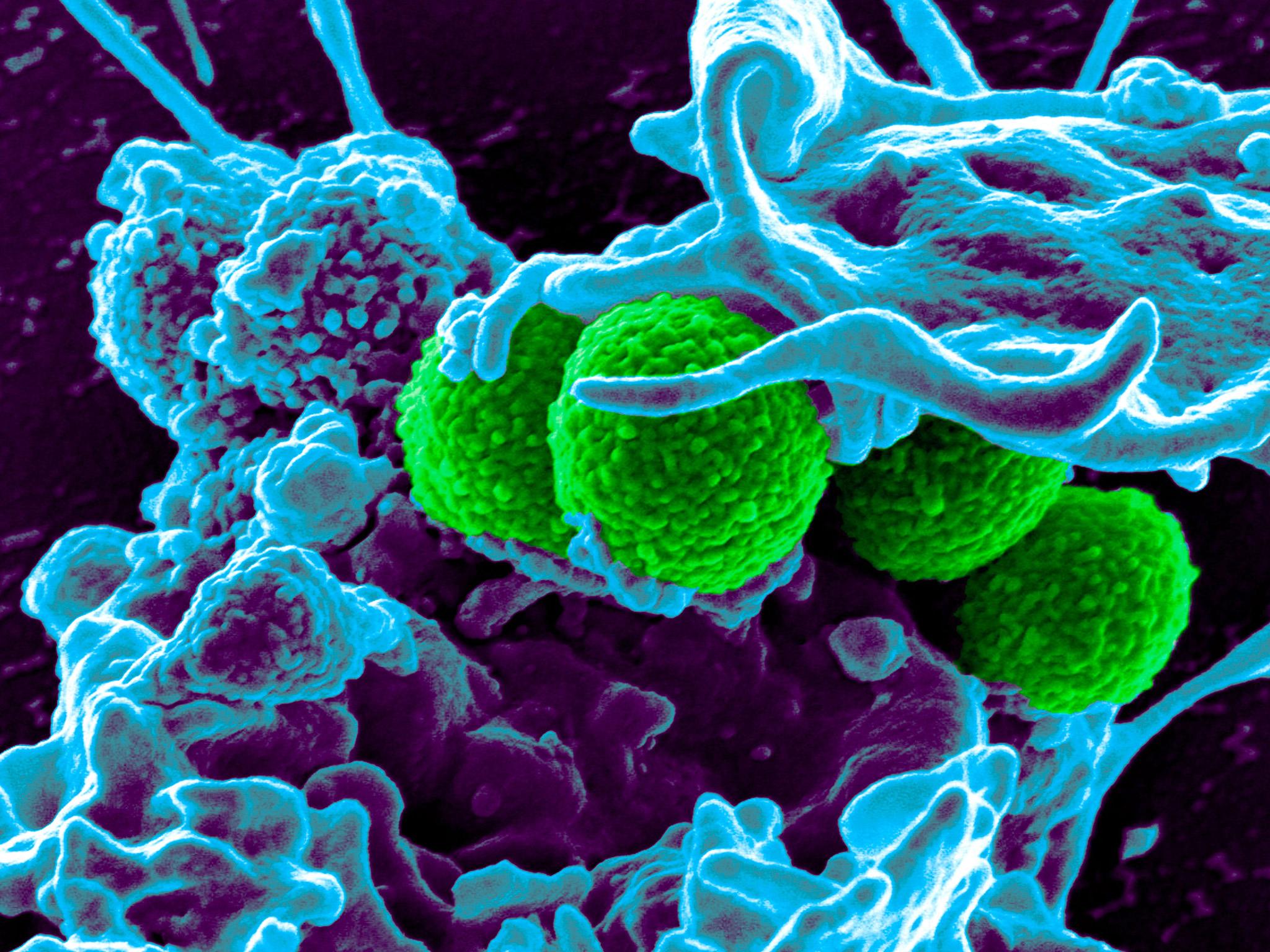

Laboratory tests have shown the new antibiotic, called teixobactin, can kill some bacteria as quickly as established antibiotics and can cure laboratory mice suffering from bacterial infections with no toxic side-effects.

Studies have also revealed the prototype drug works against harmful bacteria in a unique way that is highly unlikely to lead to drug-resistance – one of the biggest stumbling blocks in developing new antibiotics.

Such a development would represent a huge boost for medicine because of growing fears that the world is running out of effective antibiotics given the rapid rise of drug-resistant strains of superbugs and the spread of these diseases around the globe.

Last year David Cameron warned that medicine could be cast back to the “dark ages” when people died of relatively trivial infections, especially following routine hospital operations, because of the lack of effective antibiotics.

Professor Kim Lewis of Northeastern University in Boston – who led the research and is working with NovoBiotic Pharmaceuticals, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which owns the patents on teixobactin – said that the first clinical trials on humans could begin in two years and, if successful, the drug could be in widespread use in 10 years.

“The problem is that pathogens are acquiring resistance faster than we can develop new antibiotics and this is causing a human health crisis. We now have some strains of tuberculosis that are resistant to all available antibiotics,” Professor Lewis said.

“Teixobactin is highly effective against tuberculosis and there is an opportunity to develop a single-drug treatment against tuberculosis based on teixobactin rather than a treatment regime based on administering three different antibiotics.”

Test-tube studies, published in the journal Nature, showed that teixobactin was able to kill bacteria as quickly as the antibiotics vancomycin and oxacillin.

Scientists at the University of Bonn in Germany have shown that teixobactin works in a unique way by binding to the fatty lipids that form the building blocks used by bacteria to manufacture their cell walls.

“This binding site represents a particular Achilles heel for antibiotic attack and this may also explain why resistance to teixobactin was not detected,” said Tanya Schneider of Bonn University.

Professor Lewis said that the failure to detect any signs of resistance to teixobactin establishes a new paradigm in the development of antibiotics, which had assumed resistance will eventually occur.

“Bacteria develop resistance by mutations in their proteins. The targets of teixobactin are not proteins, they are polymer precursors of cell wall building blocks so there is really nothing to mutate,” Professor Lewis said.

“We’ve been operating under the dogma that the development of resistance is inevitable and we need to focus on introducing antibiotics faster than pathogens can acquire resistance,” he said.

“Teixobactin gives us an example of how we can develop an alternative strategy on developing compounds where resistance is not going to rapidly develop,” he added.

About 25,000 people a year in Europe alone already die from infections that are resistant to antibiotics and the World Health Organisation has described the rise of antibiotic-resistance as one of the most significant global risks facing modern medicine.

Professor Mark Woolhouse, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh, said: “Any report of a new antibiotic is auspicious, but what most excites me about [this research] is the tantalising prospect that this discovery is just the tip of the iceberg... It may be that we will find more, perhaps many more, antibiotics using these latest techniques. We should certainly be trying – the antibiotic pipeline has been drying up for many years now; we need to open it up again, and develop alternatives to antibiotics at the same time, if we are to avert a public health disaster.”

But Dr Angelika Gründling, Reader in Molecular Microbiology at Imperial College London, said: “It’s important to bear in mind that the new antibiotic only works against certain types of bacteria – such as MRSA and streptococcus, and not on other multi-drug resistant pathogens such as E. coli... And of course the new antibiotic described in the paper has yet to be tested in humans. It is possible that it might not be as effective as hoped and there could be unforeseen side-effects that might limit its use.”

Searching in the soil: New antibiotics

The first antibiotic was discovered by Alexander Fleming who identified penicillin microbes living in a discarded Petri dish left in his lab.

The “golden age” of discovery came in the period between 1940 and 1960 when scientists searched for microbes living in soil and sediments that could produce chemical toxins which killed other microbes.

More recently, the search focused on the “targeted” approach of designing specific chemicals to interfere with the vital molecules used by microbes to grow. Although this was successful for the discovery of new drugs, it has led to few new antibiotics.

The latest discovery has gone back to looking in the soil. But instead of trying to grow these soil microbes in the lab, the scientists have used an iChip device which can screen for microbes in their own environment when placed in the ground.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments