Exclusive: A Médecins Sans Frontières specialist on how the unprecedented spread of the ebola virus in west Africa makes the work of medics tougher than ever

It continues to ravage west Africa, with 101 confirmed dead this week. An epidemiologist with MSF on the detective work required to stop its spread across the continent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I received a message at home in Brussels about this strange disease which had broken out in Guédeckou, in southern Guinea. They thought that perhaps it was Lassa fever, but when I received a description of the patients' symptoms, it was clear to me that we were talking about ebola. A couple of days later I was in Guinea.

I've worked in every major outbreak of ebola since 2000. What makes this one different is its geographical spread, which is unprecedented. There are cases in at least six towns in Guinea, as well as across the border in Liberia. The problem is that everybody moves around – infected people move from one village to another while they're still well enough to walk; even the dead bodies are moved from place to place. So, as an epidemiologist tracking the disease, it's like doing detective work.

The other problem is that ebola has never been confirmed before in Guinea, so you can be blamed for being the messenger – you're the guy bringing the bad news that the village has been touched by ebola. To them it means death, so people often refuse to believe the reality.

We were tracing a patient who we finally found staying with family members in a very small village. He was an educated man – a professor. He'd become infected while caring for a colleague, who had caught the disease by caring for his sick uncle – when somebody is sick in Guinea, they are always cared for by people of the same sex.

The professor realised it was probably better for him to come with us to the MSF centre, but his nephew and an elderly female relative suddenly appeared and took the sick patient off into the forest. They had no confidence in the health system, and believed that people were killed in our centres, so they decided to keep their relative in the forest and cure him with leaves and herbs.

I followed them into the forest. They were very aggressive – the nephew took a big stick and was hitting the ground – but behind the aggression you could hear the pain in his voice. Eventually, we got a sample from the sick man, to make a proper diagnosis. The next day he asked us to come and collect him.

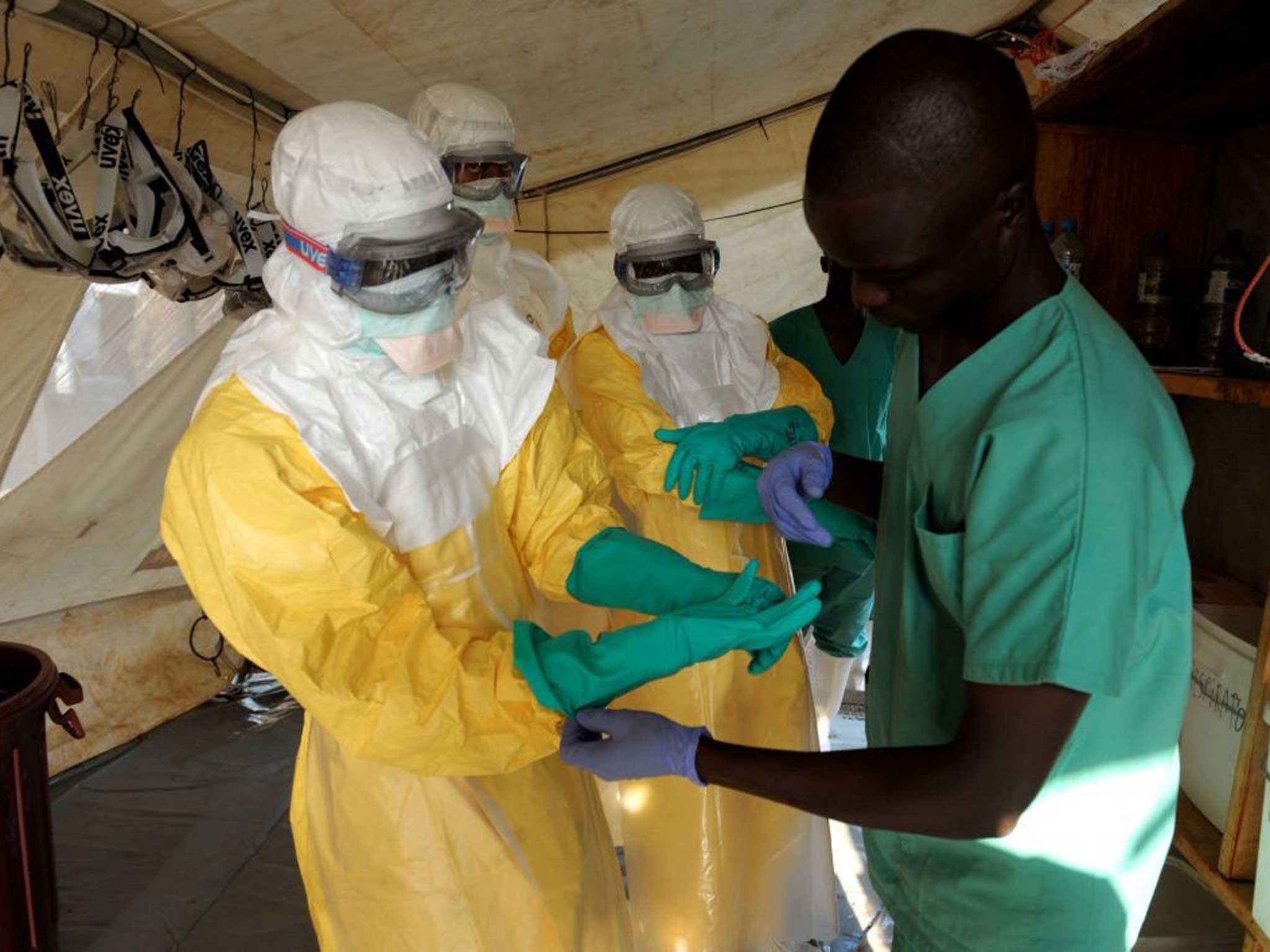

Patients are cared for in the MSF centre. For health staff, it is normal to feel some kind of fear when you enter the isolation area for the first time, even if you are well protected. But you follow a kind of ritual – for dressing and undressing, and for all the activities you perform inside – little by little, you gain confidence.

You never enter the isolation area alone – you always enter in pairs. And you only go in for short periods, because it is very hot in Guinea and even hotter inside the yellow protective suits. It is tiring, especially if you are doing physical work. We always write our names on the front of our aprons so that the patients know who is in front of them.

Inside the centre, we try and make the patients as comfortable as possible. Sometimes we bring the parent of a sick person in to visit them. They have to wear a protective suit with a mask and goggles and gloves. The relatives are supervised, so there is no possibility of any contact with a patient's bodily fluids.

Patients who are deeply affected by the disease do not have a lot of energy to communicate. The mood can be very sombre with those in a terminal stage, who have only a few hours left before they die.

When a patient dies, we put them in a special body bag so that the burial can be done according to family traditions. If the patient comes from a village, we take the body back and advise relatives about what they can do – and what they should not be afraid to do – during the funeral. Once the body bag has been sprayed, it can be handled with gloves, so the mourners can wear their normal clothes to the funeral. We do not steal the body from the family; we try to treat it with dignity, and respect their traditions as much as possible.

The mortality rate for ebola is high, but there are survivors. Just before I left Guinea, our first two patients left the MSF centre cured of the disease: Théréèse, 35, and Rose, 18. Both are from the same extended family, which had already seen seven or 10 deaths from the disease.

Their relatives were overjoyed. There was a huge celebration in the village when they returned. They come from a family of local healers, so the news that they were cured will spread to other villages, and I hope this will create further trust.

People can survive; as the patients left, our teams were cheering. To know that they survived helps you forget all the bad things.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments