Common cold vaccine patent registered by scientist who discovered body ‘fights disease in wrong way’

Vaccine 'in reach' and could be available in six to eight years, says Professor Rudolf Valenta

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A scientist has registered a patent for a vaccination against the common cold – a condition doctors have long thought could only be beaten by bed rest and plenty of fluids.

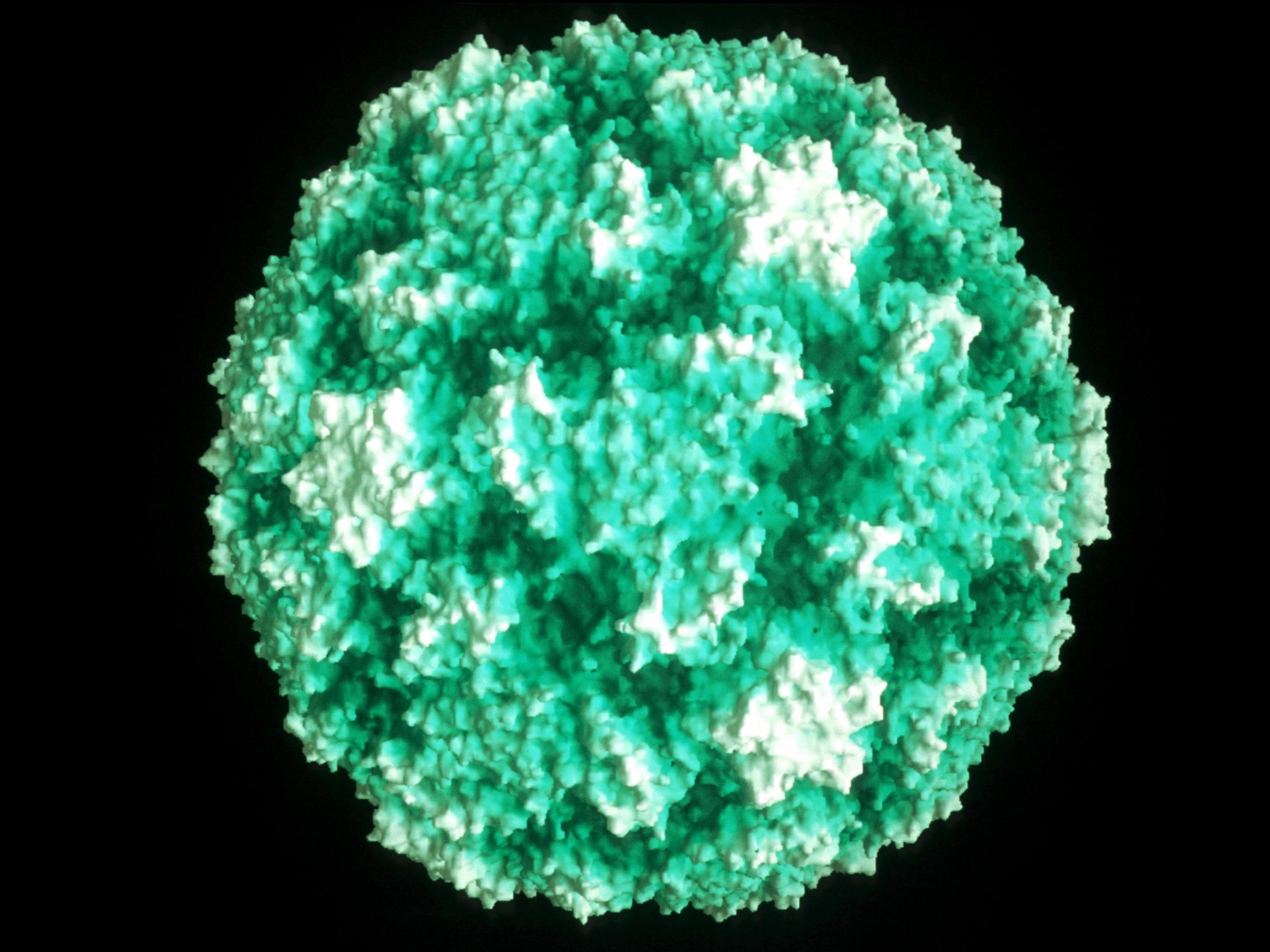

Rudolf Valenta, an allergy expert at the Medical University of Vienna, is behind the research into rhinovirus, the microbes responsible for runny noses and sore throats.

The common cold is considered difficult to treat and protect against because it has so many different strains.

But Professor Valenta told The Independent the body’s immune system tends to attack the centre of the virus, which isn’t the most effective way to fight the disease.

Instead, his vaccine focuses on the virus’s shell, which facilitates infection by attaching itself to mucous membranes in the mouth, throat, nasal passages and stomach.

"We've taken pieces of the rhinovirus shell, the right pieces, and attached it to a carrier protein," he said. "It’s a very old principle, to refocus the antibody response."

"The diversity [of different types of the virus] is less of an issue than getting the right spot on the virus."

The vaccine encourages the body to recognise and develop defences against the outer part of rhinoviruses, which are similar in all different strains.

Colds are caught by inhaling or otherwise coming into contact with infected droplets spread by coughing and sneezing.

Profesor Valenta said the vaccine could be ready to administer to patients in six to eight years.

“With the first protein we built, we have very good inhibition [of the disease] already. We believe that we are on a really good track with what we’re doing,” he said.

“If we get also the trial funded properly, it could be done between six to eight years. We know how to build the vaccines and get it to the clinic. This is really in reach.”

Jonathan Ball, Professor of Molecular Virology at the University of Nottingham, told The Independent the researchers “might be onto something” but filing a patent was “a long way away from having an approved vaccine”.

“Rhinoviruses are renowned for their variability and their ability to mutate in order escape our immunity and cause reinfections throughout life,” he said.

“There are more than a 100 different flavours and finding a vaccine that will protect against all of these will be tricky.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments