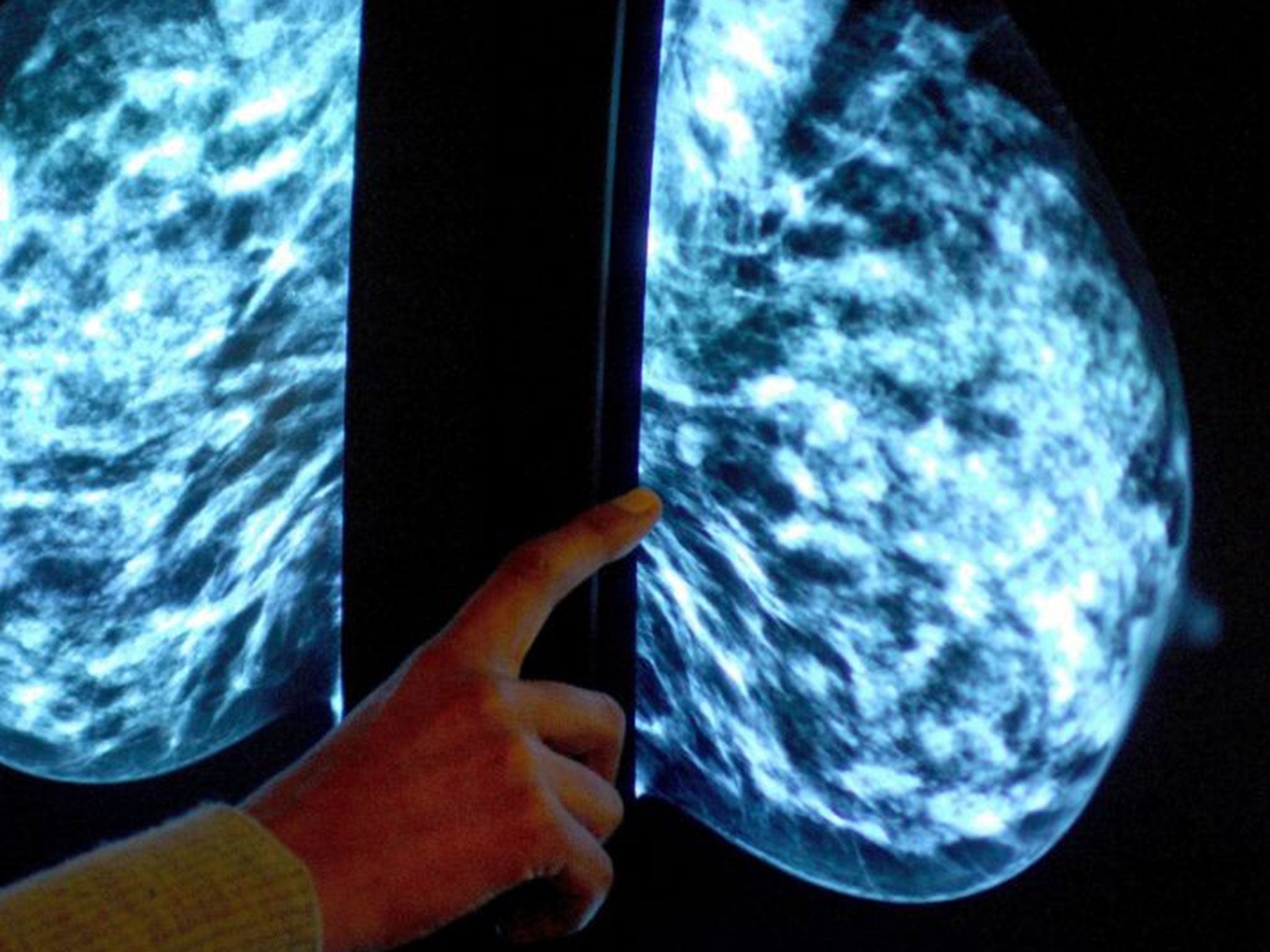

Australian researchers discover 'surprise' drug treatment for breast cancer

Calcium-binding drugs commonly used to treat people with osteoporosis could also benefit breast cancer patients

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Australian researchers have made a "surprising" discovery that could help to treat breast cancer patients.

Scroll down for video

Researchers at Sydney’s Garvan Institute of Medical Research have found that calcium-binding drugs commonly used to treat people with osteoporosis, or with late-stage cancers that have metastasised, may also benefit patients with tumours outside the skeleton, including in the breast.

In a number of earlier clinical trials, women suffering from early-stage breast cancer were given the drugs, known as bisphosphonates, in addition to their normal treatment.

The results showed that the drugs act as a "survival advantage" and, in some cases, can also prevent the cancer from spreading - but it was not understood why this was the case.

In the latest study, Professor Mike Rogers, Doctor Tri Phan and Doctor Simon Junankar used sophisticated imaging technologies to show that bisphosphonates attach to tiny calcifications in tumours in mice.

These calcium-drug complexes are then devoured by "macrophages" - immune cells that the cancer hijacks early in its development to conceal its existence.

This clip shows real-time distribution and uptake of bisphophonate (tagged red) in a breast tumour. The calcium-bisphosphonate complexes become visible towards the end of the clip - as dots of red.

Professor Rogers said: "We do not yet fully understand how the macrophages revert from being 'bad cops' to being 'good cops', although it is clear that this immune cell interacts with tumours, and probably changes its function in the presence of bisphosphonates.

"The surprising thing is that we didn’t make the connection between bisphosphonates and tumour calcifications before - of course bisphosphonates are going to bind to calcium! It had been staring us in the face for a long time, yet we didn’t explore that action of the drug. Perhaps because there is such strong acceptance that these drugs only work in bone."

Doctor Phan added: "I clearly remember the moment we first saw macrophages behaving like little Pacmen and gobbling up the drug. It was astounding.

"Our next step will be to analyse the changes that take place in macrophages, so that we can understand their change in function, and effect on cancer cells."

The researchers also analysed tissue samples from cancer patients and believe that the findings, which were published in the journal Cancer Discovery, are also relevant to humans.

They worked with colleagues at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, and obtained a tumour sample from a patient with breast cancer who had undergone surgery. They stained the tissue for calcifications, and found them next to and even inside macrophages, indicating that the same process happens in humans.

"This study is potentially transformative for treatment of some cancers, because it is telling us for the first time that drugs we thought acted only in bone can also act within tumours completely outside the skeleton, and have a beneficial effect," said Professor Rogers.

"We already know this drug is well-tolerated in people and provides a survival advantage for some patients with certain cancers when taken early in disease development. This now provides a rationale for using these drugs in a different, and potentially more effective, way in the clinic."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments