The genetics of anorexia: can it be inherited?

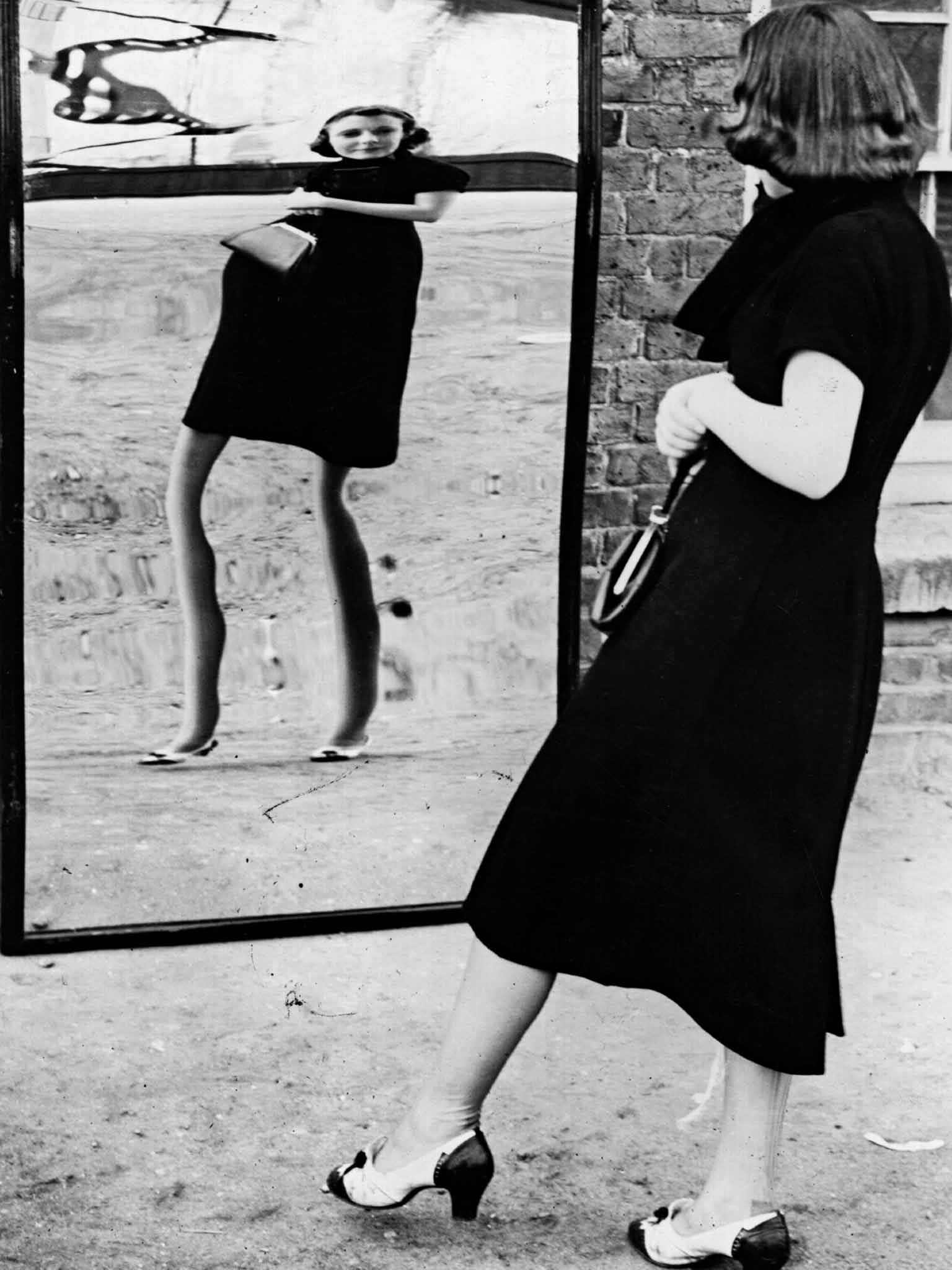

Anorexia has been blamed on skinny models and pushy parents – but more than half of the risk is inherited, studies show. Now the hunt is on to find which genes are behind it.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Social pressure to be as slender as a catwalk model, as sylph-like as a Hollywood star, is said to be what drives anorexia, the so-called slimmer's disease. An estimated one million people in Britain suffer from the disorder, which has the highest death rate – from suicide or starvation – of any mental health condition.

In reality, there is no single social cause. Psychologists say that anorexia may be driven by a fear of adulthood or of losing the attention of parents. It may represent an attempt to exert control by individuals who sense they lack it in other areas of their lives.

But an area that remains unexplored – relatively – is the genetics of the condition. Is anorexia inherited and, if so, which genes are involved? Despite decades of research into the genetics of other psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, anorexia has had little attention from the gene hunters.

Now British and American researchers have joined forces with others around the world to launch the largest-ever study of the genes underlying anorexia. The aim is to gather 25,000 DNA samples from sufferers, including 1,000 from Britain, and compare them with an unaffected control group of 25,000.

The scientists hope that by pinpointing the genes responsible and identifying their function, the research will point the way to new treatments. A study last year suggested that a cholesterol gene could play a role in the disease, providing a potential new target for drug treatment. But the finding could not be replicated (and thus confirmed); the scientists are back at square one and the hunt begins again.

One effect of the research, if it is successful, is that it could lessen the guilt that parents often feel for a condition that is thought to derive from factors in the environment and family backgrounds of sufferers.

Professor Janet Treasure, director of the Eating Disorders Unit at the Bethlem Royal Hospital, the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, says: "Guilt is a very common feeling among parents. When it [anorexia] happens on your watch in adolescence, it is a natural response. We know that anxiety in the parents can contribute to anxiety in the child. These emotional reactions are very important in allowing the illness to stick."

But she adds that too great an emphasis on the genetic basis of the illness could cause parents to feel fatalistic. "They could feel hopeless – we don't want that. We know that there is a mix of environmental and genetic causes of anorexia."

Anorexia affects 1-2 per cent of teenagers and university students, though it can occur at any age. Anorexics severely restrict eating and become emaciated, yet see themselves as fat. They secretly starve themselves, sometimes inducing themselves to vomit after eating, and usually combine this with excessive exercise. They may also take laxatives.

Sufferers tend to be perfectionist, anxious or depressed, and obsessive. The condition is 10 times more frequent among women than men and is commonest among the daughters of professional couples.

Some experts believe that the biological basis of anorexia has been under-emphasised, and the social causes over-stressed. Given the pressure on women to be thin in Western societies, everyone would be anorexic if that were the only factor, they say. These scientists say that some people are born with a biological predisposition to anorexia, which may run in families. Twin studies have already suggested a genetic link.

The global project to find the genes responsible, called AN25k, is led by Professor Cynthia Bulik, an expert in eating disorders at the University of North Carolina in the US. In the UK, the project is being spearheaded by researchers at King's College, London, who have already analysed the DNA of more than 300 former anorexia sufferers.

The King's researchers have teamed up with the charity Charlotte's Helix to raise money for the project. The charity was set up in memory of Charlotte Bevan, who died of cancer aged 48 in January. Her daughter, Georgie, was diagnosed with anorexia aged 12, and Charlotte was convinced that Georgie had inherited the condition but felt frustrated by the lack of research. She set up the charity before she died and wrote a book about anorexia for other parents, called Throwing Starfish Across the Sea.

"I want people to stop being afraid and ashamed of something that is not their fault. I want to educate the 99 per cent of the world that don't know or don't care that the eating disorder world deserves a voice. I want people to know that my daughter is not a vain, mindless bimbo who just wants to be thin, but a stellar, brilliant, important part of the community who just happens to have a brain blip," she wrote.

Gerome Breen, senior lecturer at King's, who is leading the study in the UK, says: "Research on anorexia is where it was on schizophrenia 20 years ago. There have been a lot of small studies producing results that don't get replicated [confirmed]. What we need is a really large sample size."

The project is likely to reveal hundreds of genes that contribute to the condition, some more strongly associated with it than others. The larger the sample of anorexia sufferers, the better the chance of establishing strong genetic links.

"Ultimately, we hope we find genetic hits that point the way to the biological systems that we need to target to develop new treatments. Studies show that 56 per cent of the risk of anorexia is contributed by genetic factors. If there were one gene associated with the illness, we would have found it already.

"What we see in many diseases, from breast cancer to diabetes, is lots of different genes, each contributing a small part of the risk. It won't predict who will become anorexic. But what genetic studies do best is point to the underlying biology of the illness," he adds.

The stigma attached to the illness has a damaging effect on families, and uncovering its genetic basis could help alleviate that, Dr Breen says. "Parents have got the impression that they are being blamed. It may not be true, but that is the impression they have got. A culture used to exist of blaming parents. What genetic studies can do is show that it is not all to do with how you grew up.

"In cancer, dementia and schizophrenia, we are using the full range of research tools to target the biology of the illness, the working of the brain or the development of new psychological therapies. On anorexia, things have tended to stay at the psychological end of the spectrum. I see this project as bringing to bear all those tools at our disposal on anorexia."

The researchers are working with parents' organisations and patients to find volunteers. Volunteers are encouraged to register with Charlotte's Helix and give blood or saliva samples and make a donation. The cost of the UK project is estimated at £100,000 and around £20,000 has been raised so far.

"We will be applying for grants from UK funding bodies, but for now, we are relying on donations from the public," says Dr Breen. "Will we succeed? We are optimists."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments