The face of fertility: why do men find women who are near ovulation more attractive?

Women are most fertile a week after their period begins. At this time, they experience changes in their psychology, behaviour, and physiology that are akin to changes we see in non-human primates. A new study suggests that women's faces also get redder - but men can't see it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s not difficult to tell when a female chimpanzee is in heat. As she nears ovulation — the point in her cycle when she’s most fertile – her bottom swells up like a balloon and turns bright pink.

Humans are obviously different. We don’t make a show of how fertile we are. But does this mean that women have evolved to conceal ovulation?

Women are most fertile during the late follicular phase of their menstrual cycle, which starts about a week after their period begins and ends a week later with ovulation. At this time, women experience subtle changes in their psychology, behaviour, and physiology that are akin to the changes we see in non-human primates.

You may have heard of Geoffrey Miller’s infamous lap-dancing study from 2007. Miller asked professional exotic dancers to keep a record of their nightly tip earnings for two months. The women also reported when their periods began and ended, so Miller could calculate when they were most fertile.

He found that the dancers received about US$67 (£42) per hour when they were near ovulation, but only US$52 (£33) at less fertile times of the month (and US$37 (£23) during their periods). This suggests that women are sufficiently more attractive at peak fertility to persuade men to part with their hard-earned cash. But why?

We don’t know for sure but it was probably a mix of signals. Research has shown that as ovulation approaches, women’s voices rise in pitch, their body odour becomes more sexually attractive, and they wear more revealing clothing.

The face of fertility

There is also some evidence that women’s faces are more attractive to both men and women near ovulation. The attractiveness effect is weaker when the women’s clothing and hair are obscured in the photograph. So clothing and hair are clearly important, but they’re not everything.

My research collaborators and I wondered whether womens' faces might be changing colour across the month. This isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. Women’s attractiveness to men doesn’t vary over the cycle if the women are wearing make-up, which implies that make-up conceals natural changes in skin appearance. And other primates, such as rhesus and Japanese macaques and mandrills, develop a redder face when they’re most fertile.

Perhaps our own species experiences a similar – if less noticeable – change in facial redness. This could certainly explain the attractiveness effect: studies have found men rate women with redder faces more attractive.

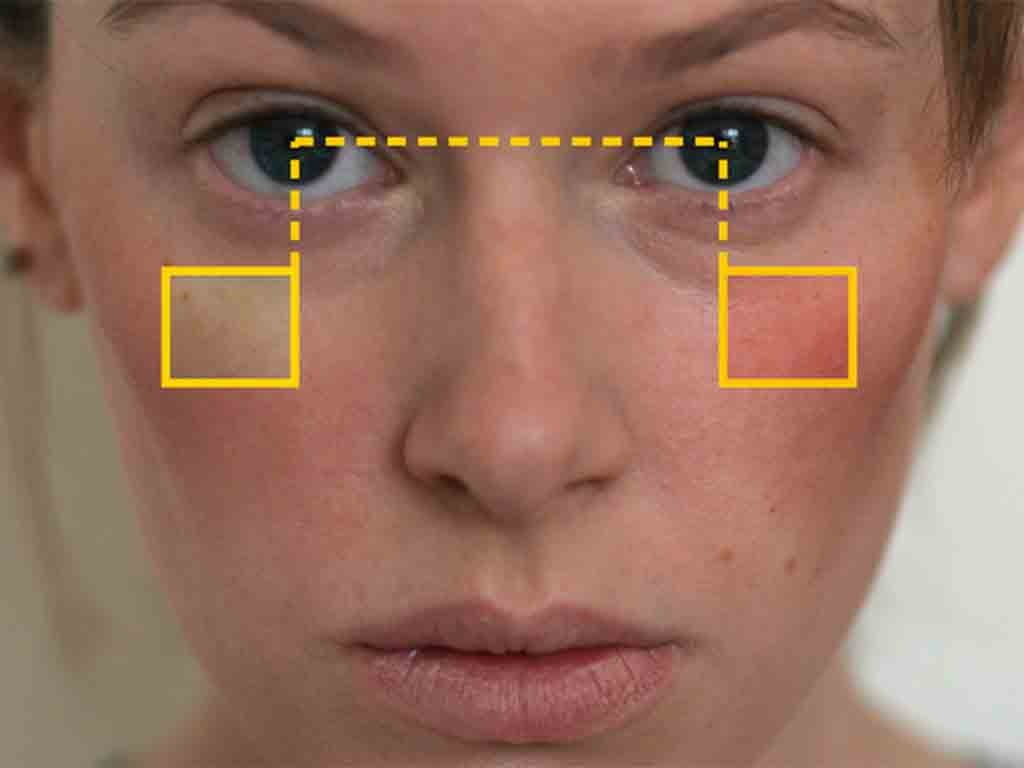

To find out, we photographed 22 young women volunteers on an average of 13 occasions and monitored where they were in their cycles, using a camera that replicated the images seen by the human eye. We asked them to avoid make-up and wear a black hairdressers’ smock so that the colour of their clothes wouldn’t be reflected onto their face (women are more likely to wear red or pink clothes when they’re fertile). Then we used a computer program to cut out patches of skin from the cheeks on each photograph.

We found women’s faces did change in redness over the cycle but not to a degree that could be seen by the human eye and therefore could not be detected by men, even unconsciously. Plus women are much more fertile just before ovulation than just after, but the redness of their faces at those two times was almost identical.

It is therefore pretty doubtful that facial skin colour is responsible for the effect of the menstrual cycle on women’s attractiveness to men. If our species ever advertised our fertility with noticeable changes in facial colour, we don’t any more.

Looking for more

It’s plausible that there are more obvious fluctuations in facial skin colour than those we detected. After all, we did only look at a small area of the cheek. Perhaps womens' lips becomes especially red at peak fertility, even without the help of lipstick (women wear more make-up near ovulation).

Some indicators of women’s fertility are stronger when women are more stimulated. Straight women are more flirtatious when fertile, but only in the presence of men they find attractive. Men find dilated pupils attractive in a woman, and heterosexual womens' pupils increase in diameter during the fertile phase, but only in response to photographs of their boyfriends.

Whatever is going on, women shouldn’t worry that they’re advertising their fertility status to men by way of a flushed red face. The changes in redness are related to cycle phase, but not to fertility or risk of conception.

nullRobert Burriss is Research fellow in Psychology at Northumbria University, Newcastle.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments