Pancreatic Cancer Action charity should realise that the disease is not a competition

An emotive campaign by the charity uses patients who 'envy' those with less lethal forms of the disease

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If you're a woman, and you just found out you had pancreatic cancer, would you wish it were just breast cancer? If you're a man, would you pine for a little touch of testicular cancer instead? Because that's the message from the British charity Pancreatic Cancer Action.

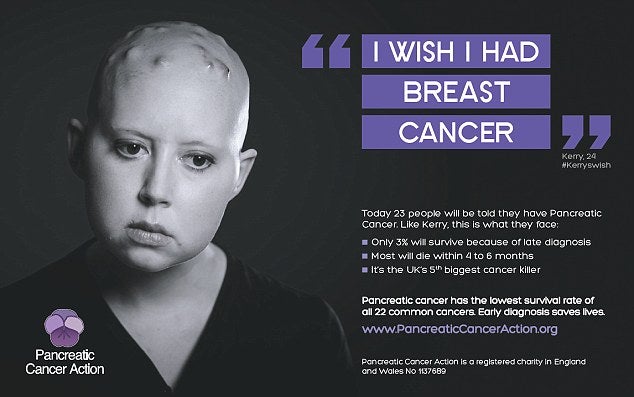

In an attention-getting campaign that launched this week, the organisation, which includes high-profile patron Hugh Grant, seeks to raise awareness of the seriousness of pancreatic cancer, one of the most fatal forms of the disease. In print messages featuring real patients that will be appearing in newspapers and Underground stations, as well as a haunting video clip, the damning statistics are revealed – it's the UK's fifth biggest cause of cancer death, with a 3 per cent survival rate. And then there's the kicker – the patients declare: "I wish I had testicular cancer" or "I wish I had breast cancer." Well, we can't all be lucky enough to get those.

In a combative blog post about the campaign, Ali Stunt, the organisation's founder and CEO, admits that it comes from a place of uncomfortable honesty. She says that when she was diagnosed in 2007, "I did feel at times that I wish I had a cancer that would give much better chance of survival; as the odds of me being around for my loved ones for longer would be significantly improved."

She goes on to relate that while she was undergoing chemo, a friend with breast cancer "was telling me how gruelling her treatment was and how difficult it was to cope with the diagnosis. While I was sympathetic and empathetic, I did find it very hard to listen to her tell me about how tough it was and that the side effects of her treatment were awful… I couldn't help but think every now and then, 'It's all right for you, you have an 85 per cent chance that you will still be here in five years' time – while my odds are only 3 per cent.' Cancer envy: I'd never have thought I would be envious of anyone with breast cancer, but I was."

Cancer is not a competition. It is not a contest to see who has the best or worst experience. But the feelings that cancer dredges up are not always pretty or heroic or brave either. Comparisons are inevitable. People who have had thyroid cancer apologetically say they had "the good kind" of cancer. There are debates over whether DCIS, or "Stage 0" breast cancer, is cancer at all. We measure the invasiveness and duration of people's treatments, the seriousness of the stagings, and accept that not all cancers are equal. To admit that takes a degree of courage, and to confess to a degree of "cancer envy" is understandable.

But that doesn't mean that a diagnosis of one form of cancer would necessarily make someone wish for a different kind. I can't speak for anyone else's experience but, believe me, when I was diagnosed with Stage 4 melanoma and faced my own statistical likelihood of imminent death, I didn't wish I'd been given breast cancer instead. You know what I wished for? To get better. I was lucky that I did. And I don't look around now at my friends with leukaemia and ovarian cancer and breast cancer and rank who has it hardest. And where Ms Stunt goes off the rails is in her post's self-exonerating quote that "No cancer advert that saves a single life can be accused of going too far."

Can we please just stop this stuff? Can we, in conversations about disease, stop relying on the atrocious "If it saves a life" crutch? It's been deployed as a "Get Out of Criticism Free" card for all manner of incredibly offensive "awareness" campaigns – many of which, no surprise, are squarely aimed at breast cancer. Why on earth would anyone want to add to the din of already offensive, insulting messages out there? Stunt says, "What we are not trying to do is to belittle any other cancer... Our advert is not stating that the person wishes they contract breast/cervical/testicular cancer, rather they wish they could swap pancreatic cancer for a cancer that will give them a better chance of survival."

You can advocate for early detection and increased awareness without crapping all over other people who are going through their own experiences. You can. And if you choose not to, I don't care if you hide behind the argument that you're "saving one life". You're being a callous jerk.

As it happens, in the middle of writing this piece, I received an email from a reader who's received a diagnosis of Stage 4 breast cancer, asking for information about clinical trials. She didn't sound like someone who felt especially lucky or relieved; she didn't say, "Oh, hey, thank God it's not pancreatic." And anybody who'd ever suggest anything even close to that to her would have to be emotionally vacant.

Breast cancer and testicular cancer are diseases, but they are experienced by real people who have pain and fear and sometimes truly crappy odds. As the I Hate Cancer blog says, "If you're going to wish for breast cancer, make sure you put in a special request for the non-metastatic kind. Because in 2014, there is no cure."

So be nice to other people with other cancers. And remember that if you're trying to win the "My cancer is worse than your cancer" award, you're in a really dumb race.

This article first appeared in Salon.com, at http://www.Salon.com. An online version remains in the Salon archives. Reprinted with permission

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments