The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Why men should check themselves for breast cancer

Men who carry a specific gene mutation are at a significantly greater risk of developing breast cancer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Screening aims to detect disease in its early stages while there’s still a chance that treatment will be effective. Programmes are usually targeted at people who are at high risk of developing a particular disease. For example, the NHS invites people over the age of 60 to be screened for bowel cancer because age is a risk factor for the disease - the older you are, the greater the risk. And for women, breast screening is automatically offered between the ages of 50-70.

But if men can get breast cancer too, why are they not included in screening programmes?

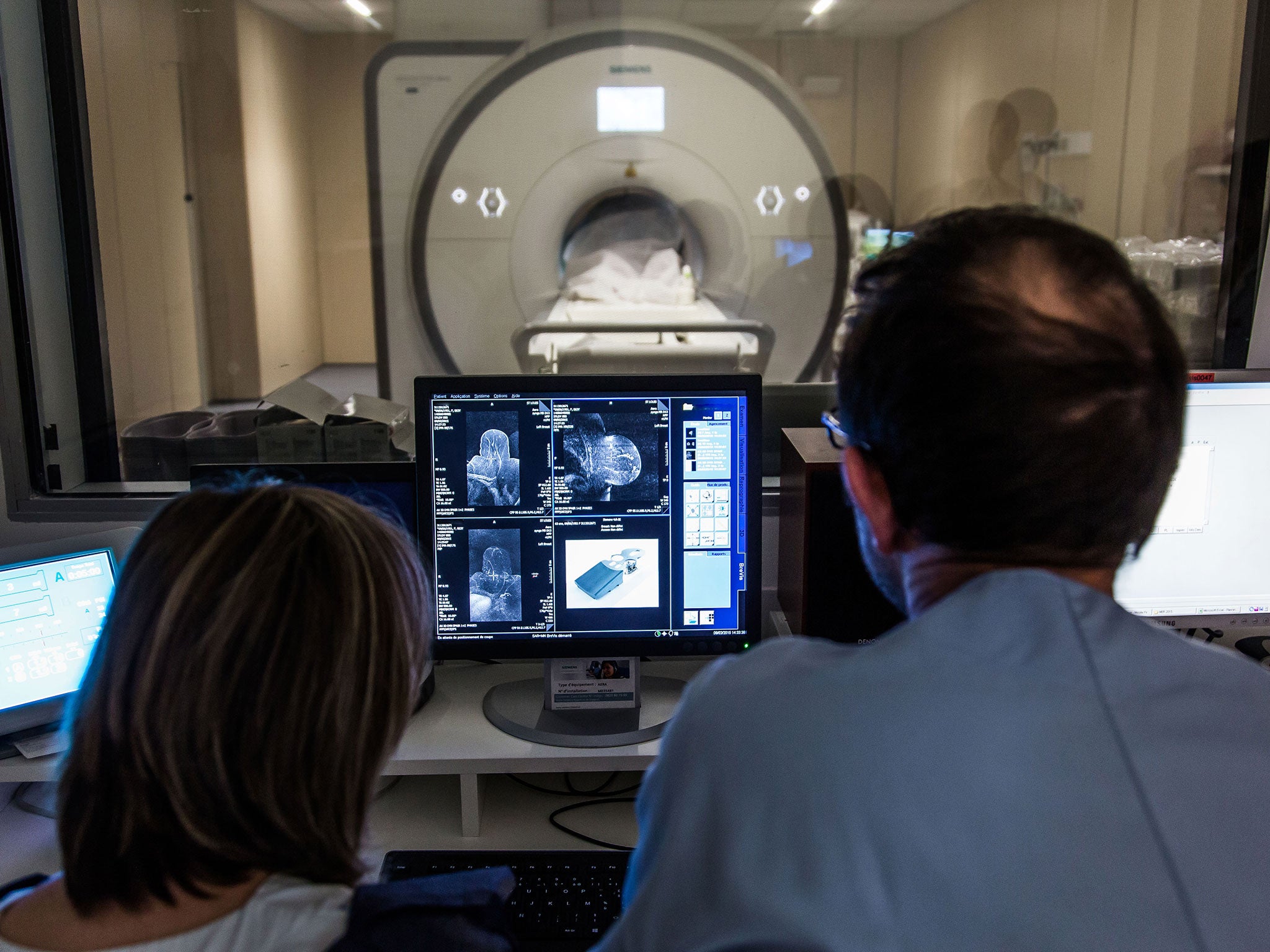

For a screening programme to be effective, a number of conditions must be met. For a start, the test should be relatively safe and it should be accurate. The main screening test for breast cancer in women is mammography. Mammography includes the use of ionising radiation, which can itself induce cancer (although the likelihood is extremely small) and the risk of a false positive diagnosis which leads to further unpleasant diagnostic tests and unnecessary anxiety.

No diagnostic test is 100 per cent accurate. But it should be accurate enough to detect the disease in most cases but not so sensitive that it detects disease when there isn’t any. Some “detect” disease that isn’t there (the “false positives”) while some fail to detect actual cases of the disease (“false negatives”). A good diagnostic test will minimise these types of errors to a negligible level.

Having an accurate test isn’t enough, though. There must be a treatment for the disease that can significantly improve the patient’s prospects. This could be a cure, but it is more often about improving the patient’s life expectancy beyond what would normally be expected if the disease was left untreated. Early detection can also result in treatment that is less invasive than if it was left until the advanced stages.

The risks associated with having a mammogram are small, as are the false positive and negative rates. Although controversy certainly exists about whether the benefits outweigh the risks, the UK, the US, Australia and many countries in Europe continue to offer breast screening programmes for women but not men.

The male question

Male breast cancer accounts for less than 1% of all cancers found in men. Compared with screening women for breast cancer, the benefits of screening men would not outweigh the risks because screening would benefit only a very small proportion of men.

It is also important to consider cost. Although justifying a screening programme on economic grounds is complex and ethically challenging, cost is an important consideration because health services have finite budgets. If the cost of mass screening for men is likely to be less than the cost of treating more cases then there would be a sound financial argument for screening, but the incidence of the disease is so low that the cost of mass screening is unlikely to be justified.

Nevertheless, breast cancer is associated with poorer outcomes in men than women because, for a number of reasons, it only becomes apparent when the disease is quite far advanced. The anatomy of the male breast means the cancer can spread to the surrounding tissue more quickly than it can in women. But men are also less aware of the signs of breast cancer and are less likely to check their breasts, so by the time the signs of the disease becomes obvious, the cancer has reached an advanced stage.

High-risk groups

So is it possible to identify men who are at high risk of developing the disease so that they can be screened? In short: yes. Men who carry a specific genetic mutation known as BRCA2 are at significantly greater risk of developing breast cancer than men who don’t carry it. Other things that put men at a greater risk of developing breast cancer are previous radiotherapy to the chest, sex hormone dysfunction, being older and having a close relative with the disease.

Some have argued that screening would be worthwhile in this high risk group, especially in those men with a history of breast cancer. In the US, the American National Comprehensive Cancer Network has suggested that men who are at high risk of developing the disease should consider having a mammogram at the age of 40 followed by yearly mammograms, depending on the findings. However, there is a shortage of high quality research to back this recommendation. Consequently no countries have introduced a national screening programme for male breast cancer.

So what can men do? Physical checks can be much more effective in men because they have a smaller amount of breast tissue. Men should get in the habit of self-examination. If they find any abnormal swelling or nipple discharge, they should visit their doctor immediately, particularly if they do fall into a high-risk group.

Leslie Robinson, Senior lecturer, University of Salford

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments