Bereaved children: We need to talk about death

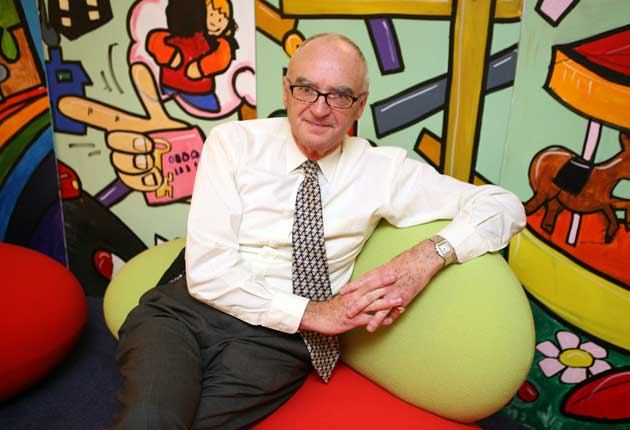

Sir Al Aynsley-Green knows how it feels to lose a parent at a young age – and now he wants to help other bereaved children. By Amol Rajan

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Not many people know that every half an hour a child in Britain loses a parent. Fewer still know that the rate at which British children lose either a grandparent, close school friend, or mentor is higher still. Our ignorance of these alarming figures is partly due to the fact that no official statistics exist for the number of young people experiencing the trauma of bereavement. The above figures are simply the conservative estimates produced by an organisation known as the Childhood Bereavement Network.

And yet the severity of the problem is beyond dispute. Bereavement means "to leave desolate or alone, especially by death". It is distinguished from grief, which means any form of deep mental anguish, by its emphasis on the solitude of those who endure it. And to a much greater extent than adults, children struggle to cope with the toxic combination of sorrow and solitude.

When married to the frequency of childhood bereavement, this presents something akin to a national disaster. It is one that the man tasked with representing children's interests to government – and we're certainly not talking about Ed Balls, the Schools Secretary here – is beginning to take seriously.

It is a curious fact that, almost immediately upon becoming the first independent Children's Commissioner in England four years ago, Sir Al Aynsley-Green set about renaming the position to which he had ascended. The Children's Commission, which he led, an off-shoot of the 2004 Children Act, had a title unbecoming of an institution whose raison d'etre was listening to children, showing them empathy, and conveying their needs to the summit of British democracy. So the Children's Commission, a name that connotes Stalin's purges, became 11 Million, which suggests warm inclusivity (there are 11 million children in Britain). Sir Al remains the Children's Commissioner.

In riverside offices next to London Bridge, whose pastel colours and overflowing children's toys evoke the sense of a kindergarten, Sir Al has invited this newspaper in for coffee to talk about bereavement. Given his stern visage, all square jaw and spectacles, on entering his office it's difficult not to feel like a guilty pupil reporting for the head master's summons. But knowledge of his distinguished previous career, in which three-and-a-half decades as a children's doctor culminated in exalted status at Great Ormond Street hospital, works as a palliative of sorts. And when he starts talking about bereaved children, the depth of his commitment to their welfare is both tangible and poignant.

"In my clinical work I've met countless families who've lost a baby or a child through illness or trauma or whatever it may be," he says. "Just working with those families and often being responsible for the management of the child that died, I've always been extremely conscious of the impact on the parents – and also on the siblings."

His "professional experience of working with very sick babies and children and seeing the impact, what happens when a child dies", is, he says, ample qualification for a new drive to improve services for children who are bereaved. But there is a second facet to his fitness for the role, the one that draws poignancy. "I can relate to these children very closely," Sir Al says, "because I was a bereaved child when my dad died unexpectedly when I was 10. I won't go into the personal circumstances but he died unexpectedly when I was 10 and the impact on me, looking back on it, was very considerable indeed".

The unforeseen tragedy was, in fact, what caused Sir Al to become a doctor. "I have come to understand the real impact as I've grown older, and I think probably a lot of the reactions I had have been sublimated or repressed in my thinking," he says. "There was one very important consequence of that bereavement, which is that I decided at the age of 10 I wanted to be a doctor. It changed my whole way of thinking as a child: I wanted to stop other people dying. It was a very child-like and childish feeling, but it certainly transformed my life."

Sir Al seems, as he vocalises his experience, to still be coming to terms with its magnitude. The repression he mentions is only vaguely palpable, so it seems sensible to ask what emotions exactly he was going through back then. "Confusion, anger, dismay. It's difficult now there's so much distance. Talking to children who've been recently bereaved, they may be very confused, they may be very angry" – his rising cadence as he says this suggests some of it may be autobiographical – "they may feel very guilty, that they are somehow responsible for the death. They may be very tearful. They may not want to show it because they see adults who are obviously experiencing grief. There are all sorts of ways children may respond: grief is a very personal reaction, so it'll impact on their emotional health, on their physical health, it'll impact on their school ability and it may have very long-term implications."

All doctors think about death more than lay people, because they are forced, far more than most, to confront its constant possibility. Sir Al has strong views on the censorship of discussion of death, which he feels is an impediment not only to our understanding and preparation for it, but also to helping those for whom death has become a big part of life.

"I think it's a taboo subject in our society. Death is something we don't like talking about," he says. "That's in stark contrast to the situation in this country 150 years ago. In Victorian times death was everywhere. Parents often expected many of their children to die and of course diseases that have disappeared now carried off countless thousands of people. So death was part of life. Now we really don't expect people to die. In medicine we try very hard to keep everyone alive."

This, clearly, is a laudable aim. But for those people, and children especially, who are forced to confront mortality, "death comes in all sorts of ways – expected and unexpected". To this end, Sir Al says he is planning to make bereavement a new pillar of the 11 Million remit. He will work with voluntary organisations including Winston's Wish, Cruse, and Jigsaw4U – all charities devoted to helping children cope with bereavement – to raise awareness of the issues and, to the extent that he can, help channel funds towards an under-nourished cause. "These voluntary organisations are trying very hard to give a first-rate service," Sir Al says, "but it's part of the problem that some kids don't have a clue they exist."

One of the triggers for his recently renewed interest was a documentary he'd seen about Winston's Wish, which focused on the weekend residential programs they run for children who have suffered loss. "One of the final clips was the sight of children where each one was given a helium balloon, and they were invited to write a message on the balloon to their loved one," he says, clearly moved by the recollection. "And they all released these balloons, and they disappeared as tiny specks in the sky, and that had a huge impact on me because when my father died I had not been allowed to see his body, I had not been allowed to talk about it, I was surrounded by adults who were obviously grieving and distressed and so on, and, in their kindness to me I think, they were trying to protect me. But the consequence was I really had a very unfortunate experience."

It's a testament to him that, five-and-a-half decades on from that trauma, his work is doing much to relieve other children of a similar fate.

Learning to grieve: How children deal with loss

* Children's response to death depends very much on their developmental stage. Up to the age of five, children view death as non-permanent and reversible, a product of "magical thinking" in which the person might come back.

* Children need to be given an honest, age-appropriate understanding of the circumstances of the death or separation to prevent them inventing things to fill the gaps, or even believing that they were in some way responsible. Even if these thoughts are not openly expressed, the child should be given lots of reassurance that they were in no way responsible.

* Despite reassurance, many children have serious misgivings about what may happen to them or others in the family, and they need to have these fears listened to and addressed.

* Children are more able to deal with stressful situations if they are given the truth and the support to deal with it. Parents should not use euphemisms to avoid the truth.

* Children and young adults in ambiguous situations take their cues for appropriate behaviour from adults and every effort should be made to demonstrate how to adapt to loss by sharing your own thoughts, experiences and memories.

By Paul Bingham, an independent chartered psychologist, practising in Northamptonshire

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments