The Web is 25: 10 things you need to know about the web (including how much it weighs)

What's the difference between the internet and the web and why do we go surfing on it?

In case you hadn't noticed, the web is 25 years young today. It's made it through growing pains and those awkward teenage years and is - supposedly - in the prime of its life.

Although not everyone thinks that this is the case (including Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the web) we thought we'd celebrate with our top ten things you need to know about the web.

The web is not the internet

The internet is the network of computers – the infrastructure of connections and servers – that shuttle data around the globe. The web is just one of the applications that use this connection (others include Skype, email and BitTorrent) to deliver data in the form of webpages.

The web was nearly called 'Tim'

When Berners-Lee first outlined his ideas for the web in a scientific paper in 1989 he referred to it as the ‘mesh’, though he also considered other names including one in honour of himself – TIM, or, The Information Mine.

We’re pretty this wasn’t an entirely serious proposal but it’s interesting to note that Berners-Lee’s original ‘mesh’ name is finding some traction again among a group of web activists hoping to re-build the web as the ‘Meshnet’ – a re-configured internet that is harder to spy on.

The NeXT computer that the web was born on.

The web was born on an Apple computer (sort of)

When Apple’s founder Steve Jobs was booted from his company in 1985 he started up rival firm NeXT. The first NeXT computer came out in 1988 and although sales were small (around 50,000 units shipped in total), it was on a NeXT computer that Bereners-Lee first set up the World Wide Web.

The only hint that this was more than a regular PC was a hand-written note on the box reading “This machine is a server. DO NOT POWER DOWN!!”

The internet was born free – but it might not continue that way

When the internet (that’s the infrastructure remember) was designed it was decided that there would be no centralised form of control and Berners-Lee was thinking in the same way when he unleashed the web to the world for free.

These decisions were incredibly momentous and have enabled what web aficionados like to refer as “permissionless innovation” – the idea that if you’ve got a bright idea for the web then you can make it happen. You don’t have ask anyone – you just do it.

Everyone from Google to Facebook to Amazon made their millions – their billions in fact – off the back of this central precept, but some people (Berners-Lee included) think the era of the free internet is under threat.

The first ever website is still running

Quite logically the first ever webpage was one that explained what the hell the web actually was. Berners-Lee created info.cern.ch in 1991, and although the site has not been constantly accessible since then, in 2013 Cern restored it to its original URL which you can browse here.

Or, if you want a more authentic experience, you can click here to experience the website before browsers (those pieces of software that help computers load pictures and complicated layouts) were invented. See the gallery below for more examples of what famous websites looked like way back when.

Soon you’ll be able to make horse.horse your homepage

Now, we say this not because we know you love horses ( best of all the animals) but because last month a whole bunch of new gTLDs (generic top-level domains) were put up for sale.

These gTLDs are the bits of a web address that come after the site’s name, and although you’ll be used to the dot coms and the dot co dot uks that are currently in use, wilder examples (including .horse, .ninja, .bike and .singles) are all on their way.

This is thanks to ICANN (the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers), the body that looks after how webpages are named, who decided that releasing new gTLDs would “ bring people communities, and businesses together in ways we never imagined” – and, you know, make a lot of money.

This is just a small part of the continuing evolution of the web. Although the varied English gTLDs may never really take off (everyone knows to ‘trust’ a .com more than a .biz – so who would trust a .guru?) ICANN is also offering gTLDs in different languages.

Currently more than 50 per cent of the web is in English (the next most frequently used language is Russian, with around 6 per cent) but experts predict that more than half of content online by 2024 could be in a script other than Latin. The web can only get bigger.

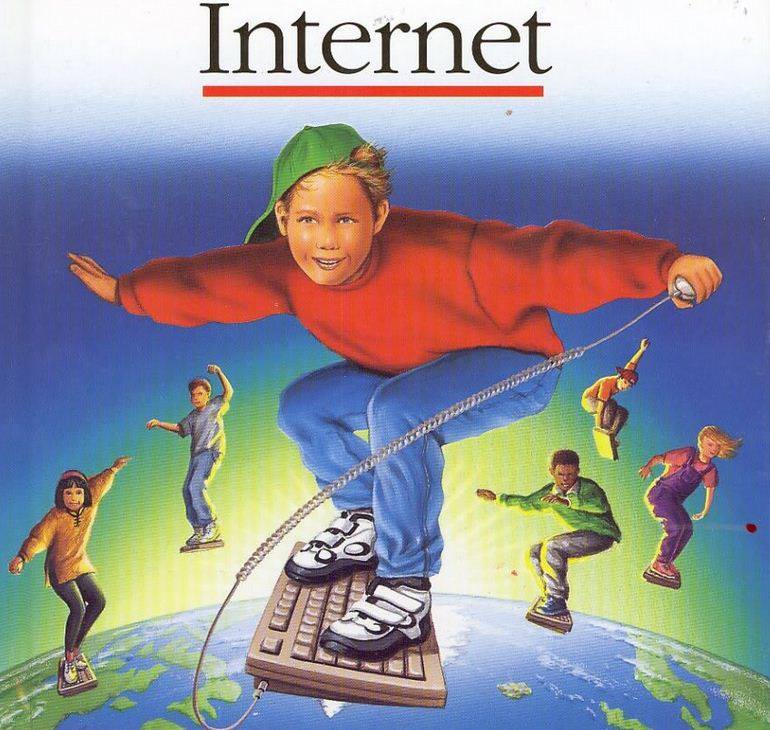

It’s called ‘surfing the web’ because of a mouse-pad

A library named Jean Armour Polly came up with the phrase back in 1992 when writing up a beginners’ guide to the web for the Wilson Library Bulletin.

She says that when looking for a title for her article she considered many metaphors but wanted something “ fishy, net-like, nautical”. Looking down she saw a mousepad with a picture of a surfer on a big wave and the image just clicked: surfing the web was born.

Like civilizations, the web has different ‘ages’

So far, we’ve only really had two of these – Web 1.0 and Web 2.0. These are distinct eras per se, but simply useful terms to describe how the early web went from a collection of static, read-only webpages to the social web (blogs, tweets, uploading and sharing) that we see today.

It’s said that Web 3.0 will be known as the “semantic web”, one that adapts to information in different contexts so that when you search something like “what shall I eat tonight” it will know more about your preferences, where you live and what’s been recommend in your area.

In some ways this vision of the web is already well on its way. Social media sites use our personal data to better target ads and services to us and as we feed more info about our lives into our smartphones (where we live, what we’re doing today, where we visit, etc) they too become smarter.

The first photo on the web was a joke

Well, to be more precise it was a picture of CERN’s house band, a comedy quartet who called themselves Les Horribles Cernettes. Bernes-Lee uploaded the picture in 1992.

Other notable internet firsts include the first domain name ever registered (symbolics.com) the first spam email (sent 3 May, 1978 on web precursor ARPANET and advertising, surprise, surprise, a new computer), the first blog (Justin Hall's 1994 site, Justin’s Links from the Underground) and the first video on YouTube (it's YouTube cofounder Jawed Karim at the zoo, uploaded in 2005).

The internet (including the web) weighs about as much as a strawberry

There’s some very rough maths behind this based on the weight of all the electrons in in the tubes of the internet. Professor John Kubiatowicz calculated that filling a 4GB Kindle would increase its weight by a billionth of a billionth of a gram (0.000000000000000001g.)

Scaling this amount of data up gives us the 50 gram weight for the web – although this is a little out of date, considering the guys who made the calculation were basing their strawberry estimate on the size of the web in 2006. But this is 2014, so it’s probably nearer to a whole punnet now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks