The end of Moore's Law? Why the theory that computer processors will double in power every two years may be becoming obsolete

Intel chief says next-generation processors would take longer to produce

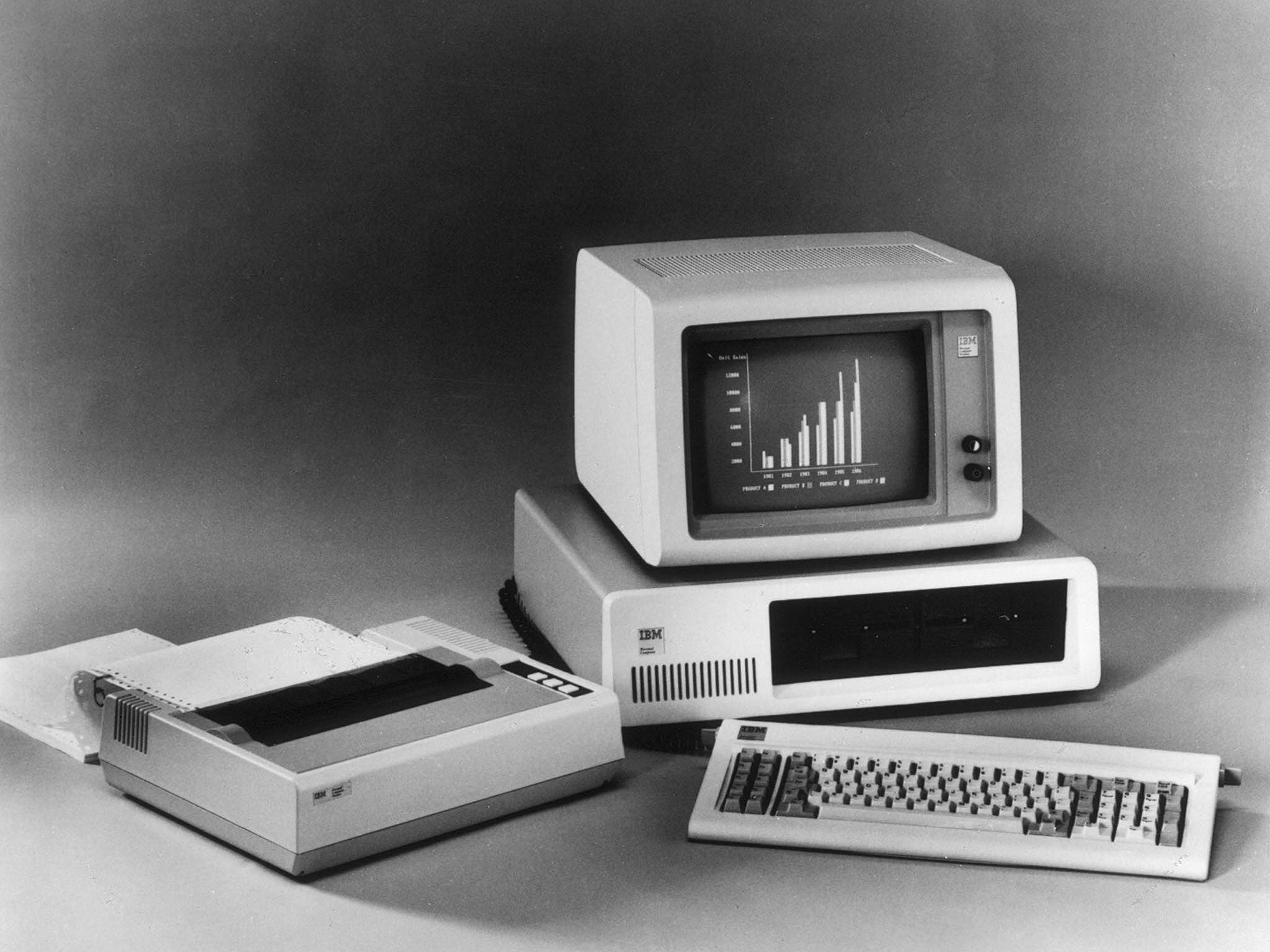

Almost exactly 50 years ago, the American electrical engineer Gordon E. Moore made a prediction which would come to have a profound impact on people’s expectations about technology. Writing in Electronics magazine in April 1965, he suggested that as advances were made, the power of the average computer processor would double every year.

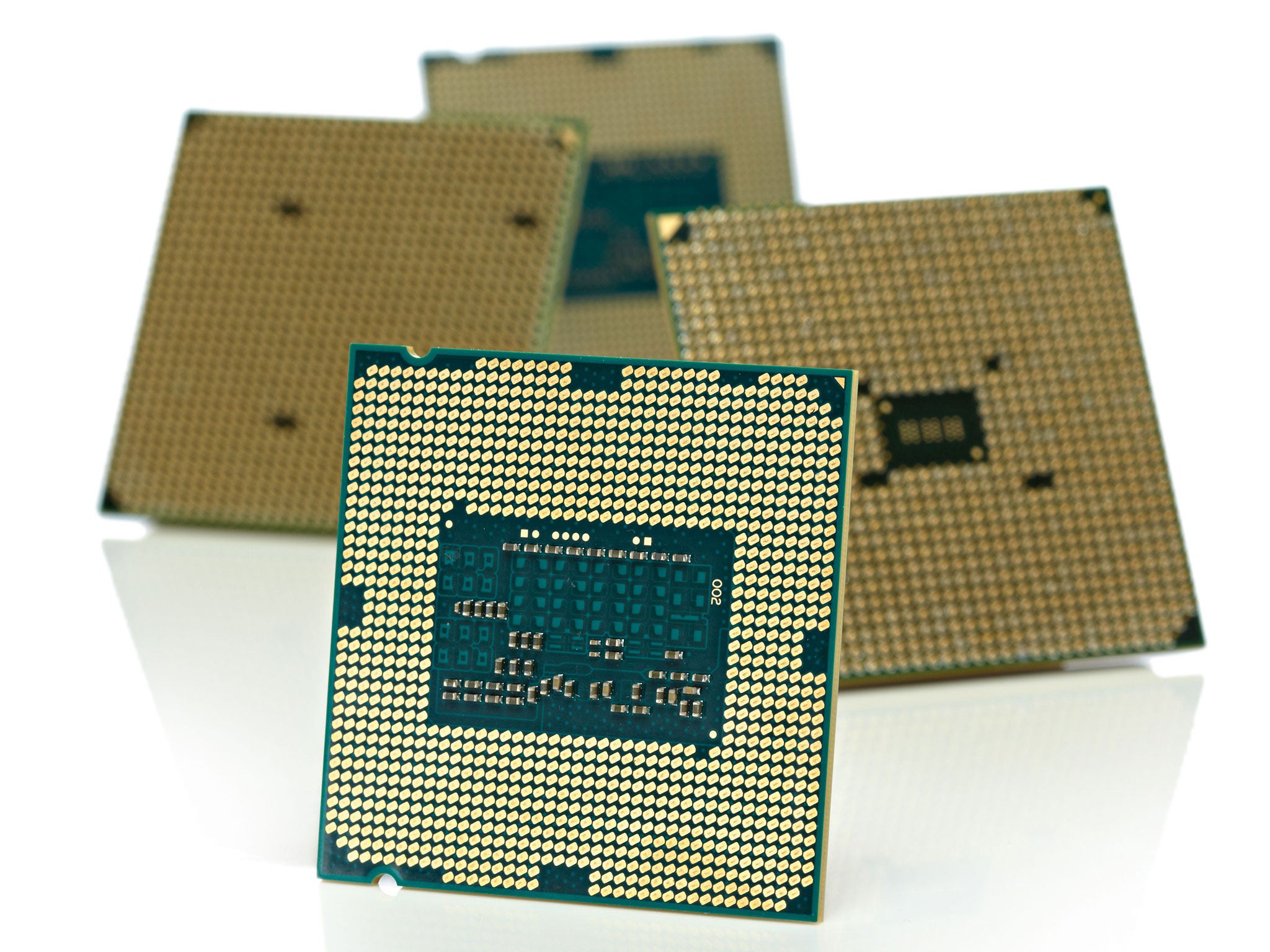

Moore went on to become a co-founder of Intel Corporation, now one of the world’s largest producers of microprocessors, which govern the speed of most laptops and PCs. His prediction, which he updated in 1975 and now states that the doubling of processor power will occur every two years, came to be known as Moore’s Law.

Since then, this two-year cycle has provided the blueprint which has underpinned the continual advances in technology to which most of us are now accustomed – and has led to consumers taking ever faster computers, more realistic computer games and better iPhones for granted.

But according to Brian Krzanich, the current chief executive of Intel, the era of Moore’s Law may be coming to a natural end. In a discussion with analysts on Wednesday night, he admitted that while his firm had “disproved the death of Moore’s Law many times over”, its next generation of microprocessors would take slightly longer to produce.

“We’ll always strive to get back to two years,” Mr Krzanich said, but added that he was “not sure” whether the delay would turn out to be a temporary phenomenon or heralded a new era of slower advances in computing technology. If other ways of building faster processors cannot be found, consumers may begin to notice that their latest phone or laptop is not that much faster than their old one, experts said.

Jason Fitzpatrick, director of the Centre for Computing History in Cambridge, said the possible demise of Moore’s Law was “not surprising” and had been expected for many years. “The number of transistors you can get into one space is limited, because you’re getting down to things that are approaching the size of an atom.”

But he added that consumers hungry for upgrades should not despair, because it was highly probable that other ways of producing more powerful chips would be found. One possibility already being explored is “parallelisation”, or the use of multiple processors working in tandem – but for this to work, existing software would have to be rewritten.

Mr Fitzpatrick added that there had “always been some debate” over whether the technology industry had only been artificially observing Moore’s Law, allowing companies to release a steady stream of better products and giving consumers an incentive to upgrade their old phones and computers. “Some people would argue that all we’ve done is held back so that we have a device we can sell next year and the year after,” he said.

But if Intel’s two-year conveyor belt does falter, other companies will be waiting in the wings eager to tap into the potentially vast financial rewards of producing the technology. Last week IBM claimed to have built processors with circuits measuring just seven nanometres wide – 10,000 times thinner than a human hair. They contain 20 billion transistors, making them four times more powerful than today’s processors, but will not be available for at least two years.

“If Moore’s Law were to hit a soft wall, the companies that know how to tackle those next escalator steps will find that their intellectual property is worth quite a bit over the next few years,” said Richard Doherty, research director at the Envisioneering Group. “IBM has made a stake at that, but that’s not necessarily the only solution.”

Beyond the public’s hankering for ever faster iPads, there is another good reason to hope that Moore’s Law continues – better processors are also more efficient, and therefore save vast amounts of energy. “Ten nanometre and seven nanometre chips will save enough electricity for several cities on Earth,” Mr Doherty added. “Servers are up to about 10 per cent of the world’s electrical use right now – they’re an inevitable part of our life.”

According to Andrew Herbert, who is currently leading the reconstruction of one of the most important early British computers at the National Museum of Computing, technology firms such as Intel have claimed the “low-hanging fruit” but were now finding it more difficult to make breakthroughs.

“It’s a bit like oil exploration: we’ve had all the stuff that’s easy to get at, and now it’s getting harder,” he said. “I’m not anticipating things coming to a grinding halt, but I think progress will be more incremental. Of course, we may find that there’s some breakthrough in the next decade that takes us off in a completely different direction.”

Geoff Blaber, an analyst at CCS Insight, said reports of Moore’s Law’s demise “continue to be greatly exaggerated”, but admitted that Mr Krzanich’s comments were “the clearest evidence to date that it is slowing and it’s a reminder that the rule won’t be relevant indefinitely”.

He continued: “Consumers won’t see any significant impact in the near term, but should Moore’s Law continue to lengthen, we should expect the big leaps in performance and battery life to slow very slightly in parallel. However, nothing is certain.”

Mr Moore appeared to predict the demise of his own law in May, when he spoke at an event in San Francisco to mark the 50th anniversary of his article. “The original prediction was to look at 10 years, which I thought was a stretch…The fact that something similar is going on for 50 years is truly amazing,” he said. “Someday it has to stop. No exponential like this goes on forever.”

Gordon E. Moore

The electrical engineer was in his 30s when he made his famous prediction in the pages of a magazine that the number of transistors which could be fitted into computer chips would double approximately every year, meaning that computers would become increasingly more powerful. In 1975 he extended the interval to two years. Now known as Moore’s Law, it has so far proved correct.

Three years after making his prediction, Moore co-founded NM Electronics alongside Robert Noyce. The company later changed its name to Intel Corporation – a portmanteau of the words “integrated” and “electronics” – and currently employs more than 100,000 people. Now aged 86, Moore is estimated to be worth more than $6.1 billion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments