Tetris can reduce risk of PTSD, scientists say

The classic game provides 'cognitive barriers' which help reduce flashbacks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

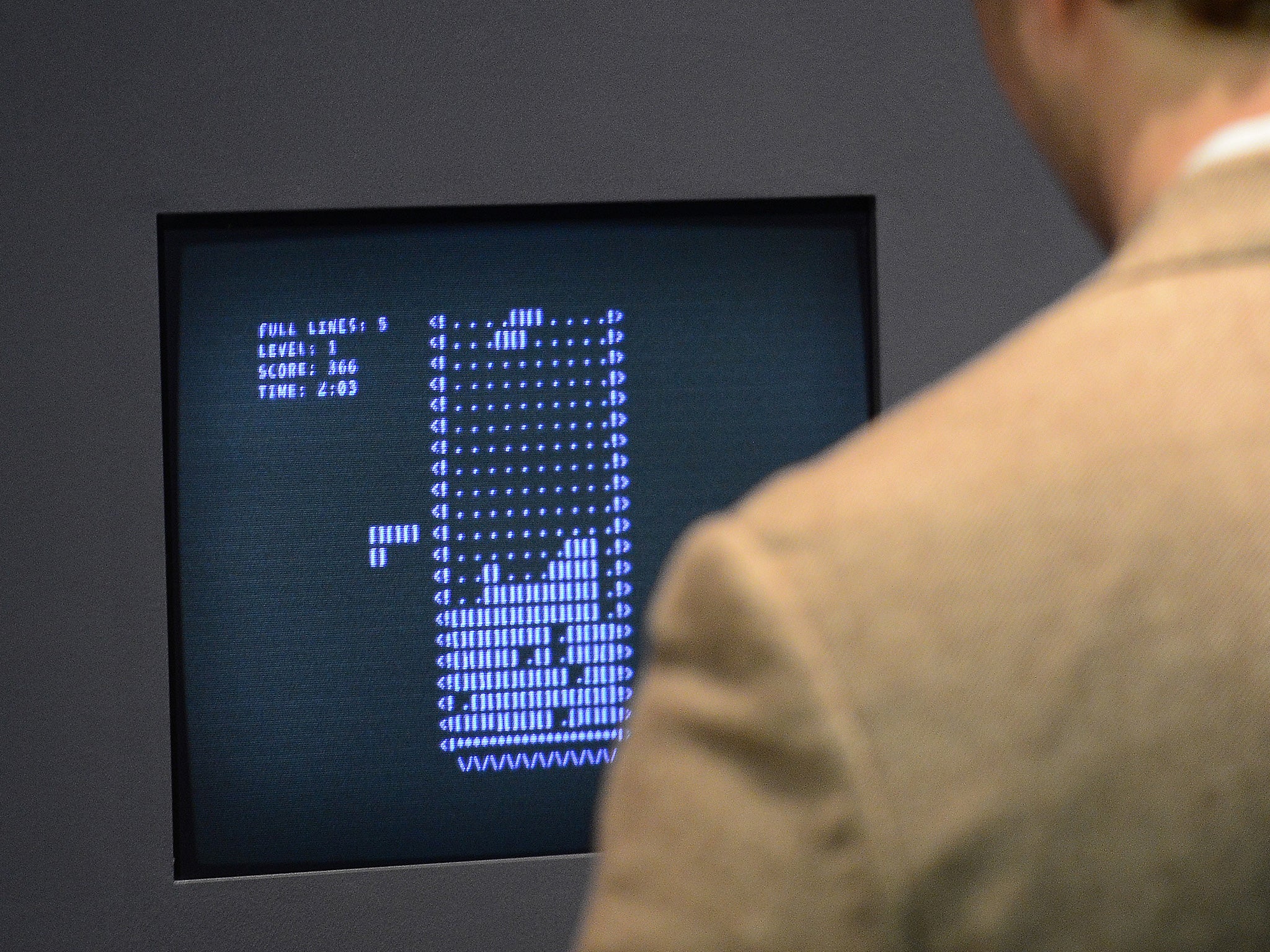

Your support makes all the difference.It is the addictive Russian-tile matching game whose popularity surged when it was released with the Nintendo Game Boy in the 1980s.

Contemporary video games may be somewhat more complex in graphics and gameplay yet bored commuters have also helped Tetris become the best-selling paid downloaded game of all time.

More than 30 years after it was created scientists believe playing the game has another benefit - blocking flashbacks of traumatic events thereby reducing the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Rape victims, soldiers and asylum seekers or refugees who have been subjected to torture, are more prone to experiencing intrusive flashbacks which, if they persist, can lead to PTSD. One in five people who have been in a serious car accident are also affected.

Although there are effective treatments for PTSD sufferers, nothing exists to help prevent it from developing in the immediate aftermath of the trauma. Scientists at the Medical Research Council Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit in Cambridge believe a dose of Tetris could be the answer.

Tetris involves piling colourful blocks of varying size without leaving any gaps as they descend at ever increasing speed. Points are awarded for every unbroken row, up to a maximum of four, which then disappear.

In 2009, the researchers showed that playing the game up to a day after being exposed to trauma reduced the number of flashbacks. The team asked 56 people to watch video footage of distressing events, such as public safety videos.

The next day the participants returned and looked at still images from the footage so their memories of the video could be reactivated. Half the participants then spent 12 minutes playing Tetris while the others, acting as controls, did nothing at all for the same length of time.

All participants were then required to keep a one-week diary of any intrusive memories that occurred - defined as “scenes of the film that appeared spontaneously and unbidden in their mind”.

Lead researcher Emily Holmes said the group that had played the game experienced 51 per cent fewer intrusive memories of the traumatising video than the group that had not. The Tetris players also scored lower on the intrusive memory section of a questionnaire used to diagnose PTSD.

Ms Holmes said playing a game that involves visual processing, like Tetris, forms a “cognitive blockade” diminishing the strength of the visual component of a traumatic memory making it harder for that event to be repeatedly triggered in the mind. The results are published in the journal Psychological Science.

She said: “We started with Tetris because there is previous research showing that it uses up visual attention. Think of it like hand washing. Hand washing is not a fancy intervention, but it can reduce all sorts of illness. This is similar – if the experimental result translates, it could be a cheap preventative measure informed by science.”

Her team is already testing the game in hospital emergency departments on people who have been involved in car accidents. Ms Holmes thinks other visually demanding games such as Candy Crush, or different visual tasks altogether, could have similar effects.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments