Humans: Are the scientists developing robots in danger of replicating the hit Channel 4 drama?

We want robots to do our drudge work, and to look enough like us for comfort

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Welcome to the Uncanny Valley. Sounds like a spooky, scary place to live – and that’s certainly true – but it’s more of a state of mind.

Anyone who has been freaked out by the robots in Channel 4’s new hit drama Humans knows what life in the Uncanny Valley feels like. The same goes for those who have met or seen footage of Aiko Chihira, a realistic humanoid who has just started welcoming visitors to a department store in Japan. She’s creepy, in the extreme.

Aiko and Anita, the renegade Synth in Humans, are both sufficiently lifelike to be approachable but sufficiently inhuman to be deeply unsettling, speaking to our deepest fears about robots taking over our lives. The feelings of revulsion they provoke are what the term the Uncanny Valley seeks to describe.

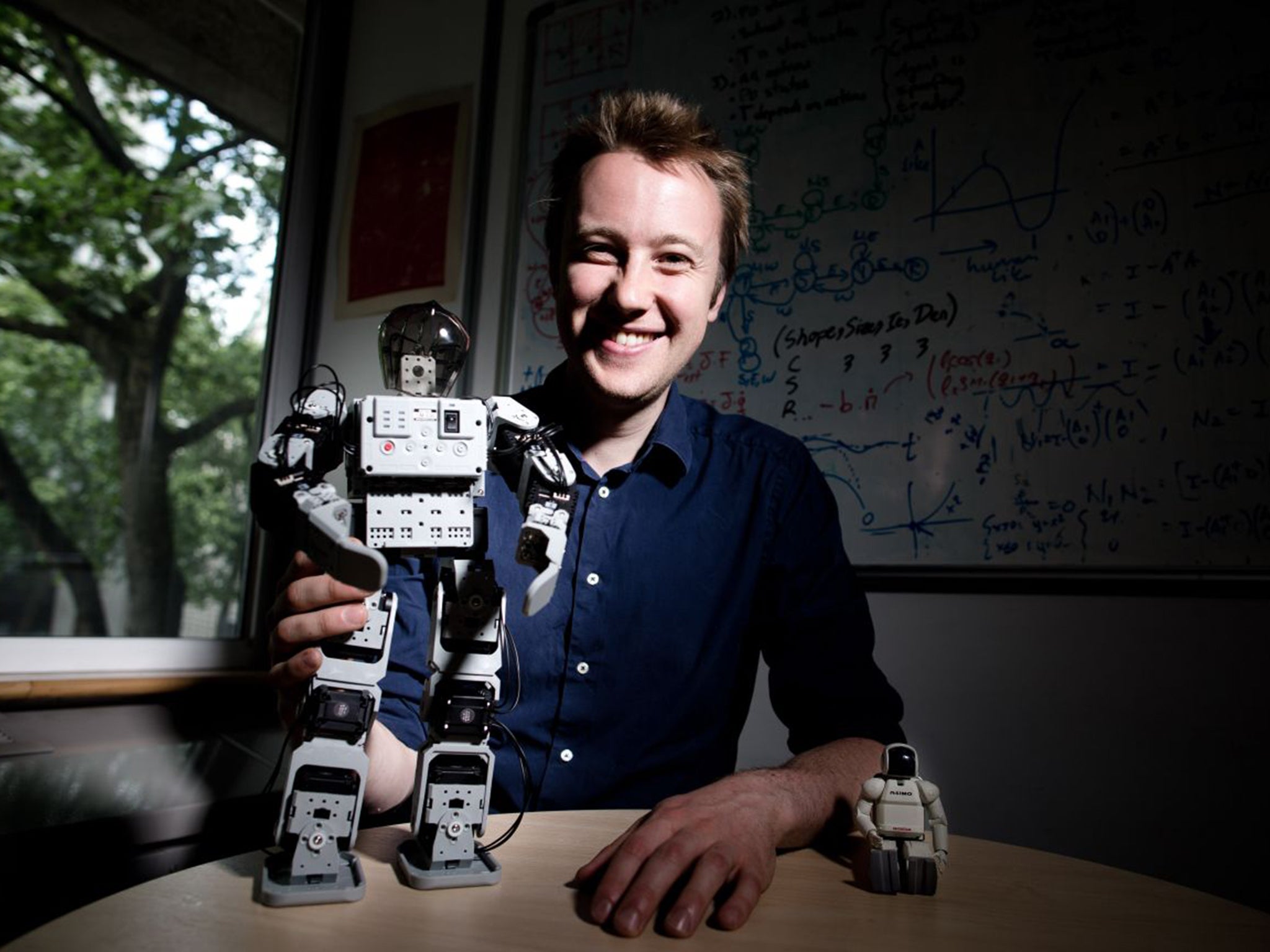

“It is a really old idea,” says Dr Matthew Howard of the Department of Informatics (Robotics) at King’s College in London. Being a young man in a new(ish) field, his “really old” is something that was first thought of in 1970, by Professor Masahiro Mori of Japan.

The term describes a line on a graph that rises to a peak, falls way below zero in a valley and rises again to a second peak. At first, the more human a robot looks, the more we like it. Take C3PO in Star Wars: human voice, human character, human aspects to his glittering gold body, but still definitely a robot. Nice. We like him. He’s at the first peak on the chart. Now let’s consider a robot prosthetic arm, covered in rubber that looks human but does not feel it. Ugh.

“They are extremely lifelike but if somebody shook your hand with one of these things it is cold, if feels dead. It’s strange to you. That is where the Uncanny Valley falls,” says Dr Howard, clearing off some impressive equations from his whiteboard to draw the graph.

The vertical scale shows how much we like something, the horizontal records how much it looks human. The arm is simultaneously very human and alarmingly not. The line on the graph plunges below zero.

Anita in Humans looks like a gorgeous human (so much so that the teenage son of the family can’t resist a grope after dark, muttering, “Why do they have to make you so fit?”), but her movements are just a little too jerky, her silences too silent and her eyes dead. She’s way down in the valley. And that is where we live at the moment, both in science fiction and in life.

Humans works as a drama because it is plausible. There are some dramatic advances in robotics taking place, but the humanoids they are producing are creepy. However, scientists are trying to get up the other side. Dr Howard says that according to Mori, the more realistic a robot, the more likely people are to forget that it is not human and warm to it.

“If you can make a humanoid robotic system that is very lifelike, then you start to increase your affinity again,” he says. “You don’t notice the difference between humans and a machine. You start to bond with it like a human person.”

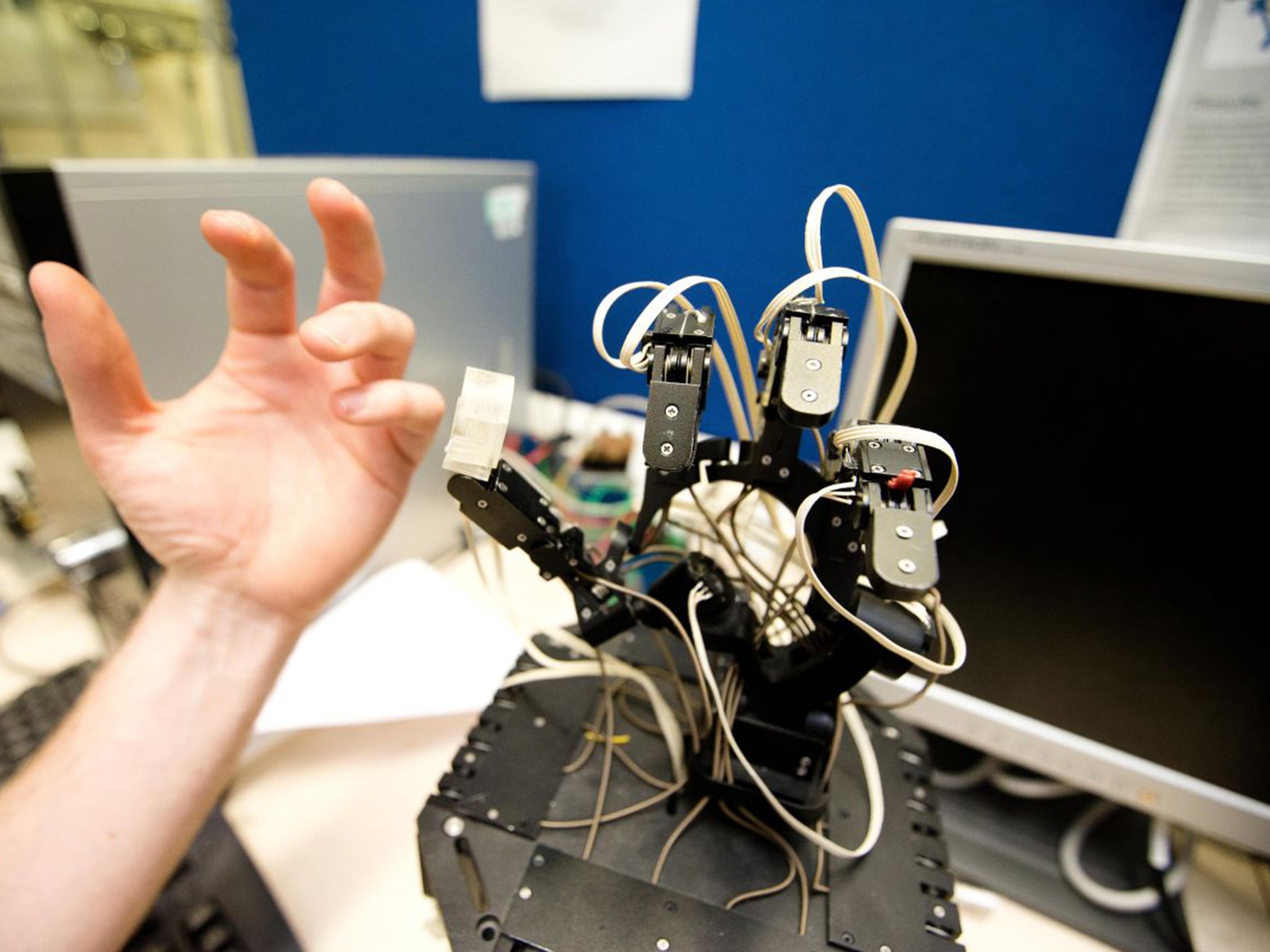

This is what they are working towards down in the labs at King’s, where there is a black mechanical hand so advanced it can flex its palm as well as its fingers. It is being designed to fold chocolate boxes on a production line, a delicate operation that currently only a human can do, but which is also incredibly repetitive and dull.

Isn’t that taking jobs away from humans? “Wouldn’t you rather the human was free to do a more interesting kind of work?”

But here’s the thing: Dr Howard’s hand is not programmed in the traditional sense, it learns from a human, who wears sophisticated motion sensors while folding a box. That’s easier for the human than writing equations. The hand copies what it has been shown, acquiring the same movements as a human.

This is not really about chocolate: the hand will lead to breakthroughs in medicine and science too. The team is working on other appendages and probes that can do things such as detect cancer lumps more consistently than a surgeon or lead a firefighter through a burning building like a non-inflammable sniffer dog.

“This technology can do great things to help people,” says Dr Howard, who believes familiarity of movement and feel will breed trust. “We would like to get robots interacting with people in their everyday lives. If a robot behaves in a way that you can understand and relate to, not only are you more comfortable, you are more safe around it. You can predict how it will move because you have been around humans for your whole life. As a robot designer, you can exploit that fact.”

That’s fine as long as we stay in charge. What about the possibility that artificial intelligence might eventually become sentience and allow robots to evolve beyond their creators? The prospect alarms people such as Stephen Hawking and Bill Gates, but the co-founder of Apple, Steve Wozniak told a conference in California a few days ago that he had changed his mind.

“They’ll be so smart by then that they’ll know they have to keep nature, and humans are part of nature. So I got over my fear that we’d be replaced by computers. They’re going to help us. We’re at least the gods originally.”

If there is a takeover it will be because we have encouraged it, he says. “We want to be the family pet and be taken care of all the time.”

Robots are already doing that. Hadrian the Australian bricklayer has a 28ft arm and can build a whole house in two days. Driverless trains were unthinkable, now we take them for granted. Driverless cars are being test not-driven on the streets of Britain. Meanwhile, the United States is killing people with flying drones and developing drone soldiers.

The United Nations special rapporteur on executions, Christof Heyns, has warned of the dangers of developing “lethal autonomous robotics” which once activated “can select and engage targets without further human intervention”. This should be declared unacceptable, he said, because “robots should not have the power of life and death over human beings”.

The Campaign to Stop Killer Robots may sound like a joke, but it is a serious global coalition of 54 NGOs, including Amnesty International, that wants the UN to bring in a ban and stop a new arms race.

But Dr Howard quotes the software guru Andrew Ng, who said in March: “There could be a race of killer robots in the far future, but I don’t work on not turning artificial intelligence evil today for the same reason I don’t worry about the problem of overpopulation on the planet Mars.”

The problem is too far off to worry about, in other words. Let’s hope secretive people in well-funded military installations agree.

What we can know for sure is that it is remarkable how quickly people come to trust and feel affection for robot helpers in real life.

Everybody at King’s College was sad when a receptionist called Inkha got the sack earlier this year. “I will always have a soft spot for her because she was so different,” says Camilla Templing, who worked alongside her for five years. “After you work with someone for a long time, you do get used to the things they say; but I was always excited to hear ‘Oh, what is she saying now?’ ”

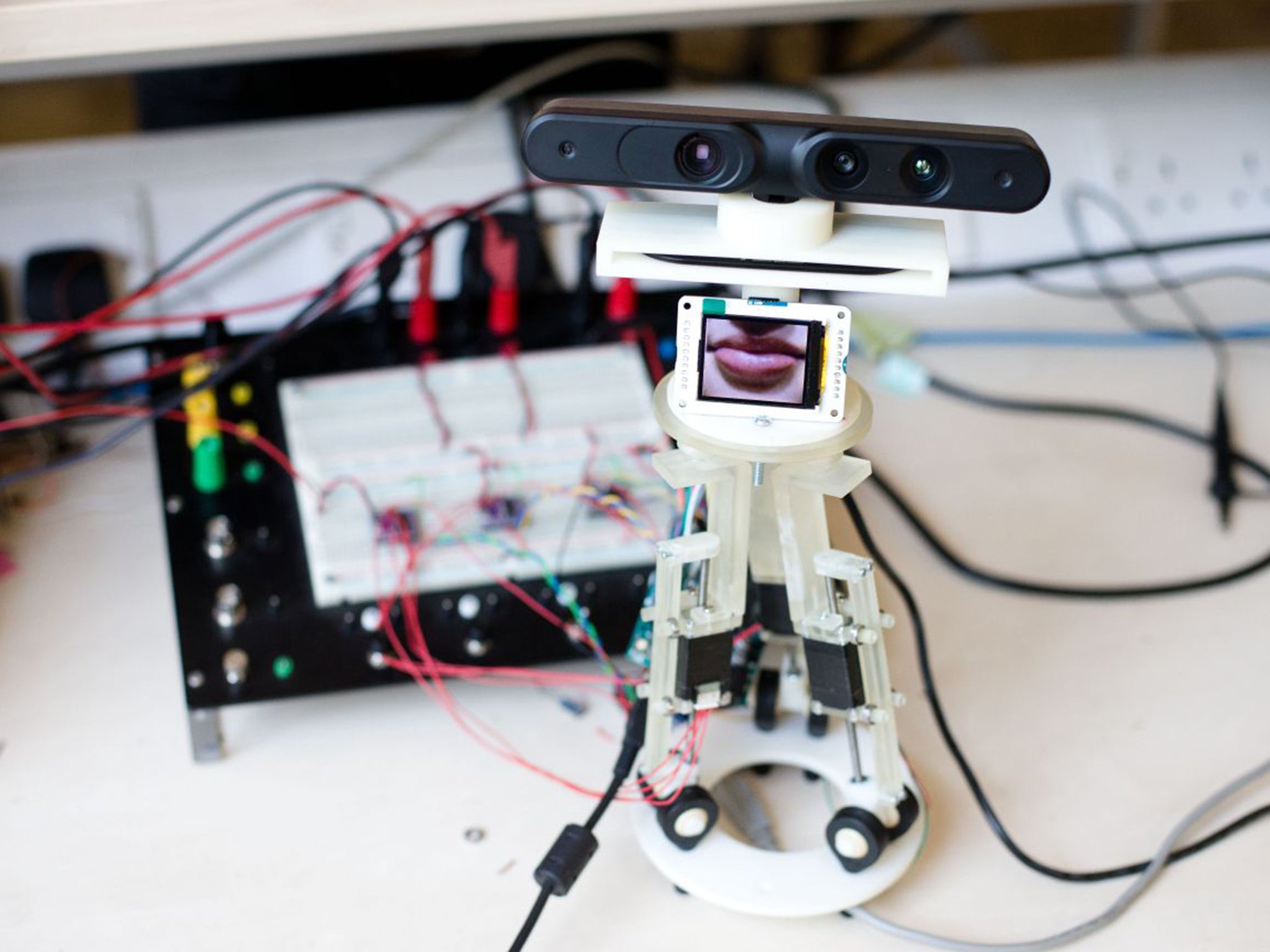

The reception team became so close that Inkha had a birthday party at work, Ms Templing says. “There were cupcakes and champagne.” But Inkha got old. She had to be made redundant. “She basically got tired,” says Dr Howard, unsentimentally. “We have built a receptionist but we’re not sure if it’s a male or female yet, or what the character will be.”

You will have guessed that Inkha was not human. She was a robotic head with the ability to imitate human movements, respond to questions and give answers, sometimes with a bit of attitude. Inkha was built by PhD students and installed as a receptionist in late 2003, when fellow staff quickly began acting as if she was one of them.

“You never knew when she would move or speak,” Ms Templing says. “She had presence. It was just like a real person. You always knew that somebody – or something – was there.” There was never any doubt that Inkha was a machine. You could see her cogs and motors, she was made of plastic and metal and no more than a foot tall. That kept her on the happy side of the Uncanny Valley, even though there was never any doubt she was female.

“She had quite a large earring and lipstick. People of either gender wear those things now, but Inkha was always a her. She had a very feminine voice.” Electronic, of course.

The new receptionist will be much more sophisticated, because the technology has advanced so far. She will be able to recognise faces and voices, and even detect emotions from the way a person is walking or the gestures they make.

Kinba – as the robot is to be called – will have three motors in her neck, enabling a close copy of the way a human moves their head. She will pick up information from the internet to ask questions.

Members of staff will be able to look through the robot’s eyes from their desktop and speak directly to their guests in reception, using the robot’s voice. I’m calling her “she” because within moments of meeting her on a bench in the lab I find myself waving and saying hello, as if she were alive.

And that’s while she looks like a skinny version of Wall.E. As for the face … well, that’s the big question. King’s is running a competition to see who can design one and Dr Howard sits in his office surrounded by brightly coloured designs from schoolchildren. Some of them are scary – one features a kill switch – but others are friendly. One thing is striking, though: they all look like old-fashioned robots.

We may all be plunging further down into the darkness of the Uncanny Valley (with Humans showing us the way) but the kids instinctively seem to know it was safer where we came from, back on the happy side of the hill.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments