Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

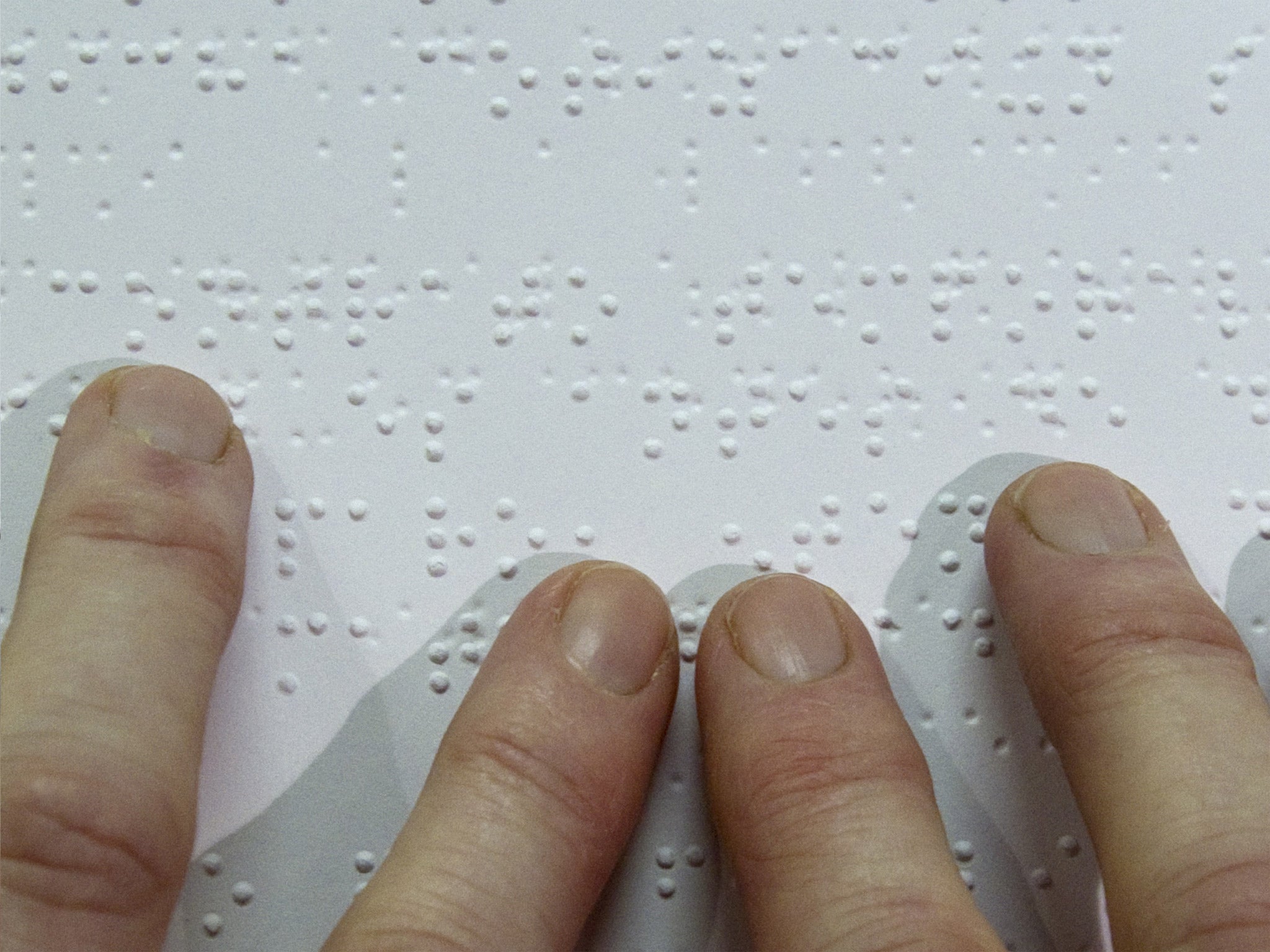

Your support makes all the difference.It took more than a century for Braille to be established as the English reading system for the blind after an acrimonious and lengthy dispute dubbed the “War of the Dots”.

Now it faces another battle as the rise of digital technology means its importance to blind people is diminishing. It might even fall into disuse altogether, according to the curator of a new exhibition.

“Braille is embattled. The biggest threat is computer technology, which makes it much easier not to have to learn it,” said Matthew Rubery, from Queen University of London.

“A lot of people fear Braille won’t survive because it will be read by so few people. The use has declined and there are concerns about funding to keep it going.”

Dr Rubery, with Birkbeck University’s Heather Tilley, is curating the exhibition How We Read: A Sensory History of Books for Blind People. The exhibition, which opens in November in London, will introduce the development of alternative ways of reading over the past two centuries.

These include the development of Braille and its embossed-print rivals, talking-book records, speech-synthesisers and systems that magnify text on computer screens.

Many of the devices have never been displayed. Dr Rubery said it was an opportunity “to explore this significant but largely neglected aspect of the nation’s literacy heritage”.

A series of competing systems emerged in the 19th century to help blind people read. Braille was a system published in 1829 by the Frenchman Louis Braille. Among its rivals were the embossed pages published by William Moon.

About 30,000 people use braille in some form today. About 6,000 of these are heavy users, according to the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB).

But it faces threats from advances in low-vision technology, the greater availability of recorded materials and reading machines. The RNIB revealed fewer people are using its Braille library. Steve Tyler, head of planning at the RNIB, said the body was worried about the decline of Braille, but that it was putting more resources into teaching products and electronic Braille.

He said: “We do see threats to the system but it is still at the heart of what we do because of its literacy and educational value.”

The exhibition will also chart the development of talking books for the blind, first provided for veterans blinded in the First World War.

Dr Rubery said: “Ever since Edison invented the phonograph in 1878, people have been listening to spoken- word recordings. But the first full-length recordings were made for blind people in the 1930s. Before, the records only allowed a few minutes.”

Among the exhibits is what is believed to be the oldest surviving talking-book record, from 1935 – the BBC announcer Anthony McDonald reading Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell.

“Blind people started listening to long-playing records 15 years before anyone else,” Dr Rubery said. The first spoken-word records released were the Bible and excerpts from Shakespeare.

The first popular novels were The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie and Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon.

Three blind types: Rival systems

Braille

Louis Braille invented his system at the age of 15, taken from a code invented to send military messages at night. He published it in 1829; it was established as the English system of choice in 1932.

Boston Line Type

Devised by Samuel Gridley Howe, founder of the New England School for the Blind, it was an embossed, simplified Roman alphabet. The first book using the system was published in 1834.

Moon

After losing much of his sight from scarlet fever as a child, William Moon developed a system of raised-print letters, which he published in 1845. It is still available in the UK and can be generated with computer software.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments