Could Apple's first mistake come back to haunt it?

Rhodri Marsden explains why the company's 'go-it-alone' strategy may leave it vulnerable to its rivals once again

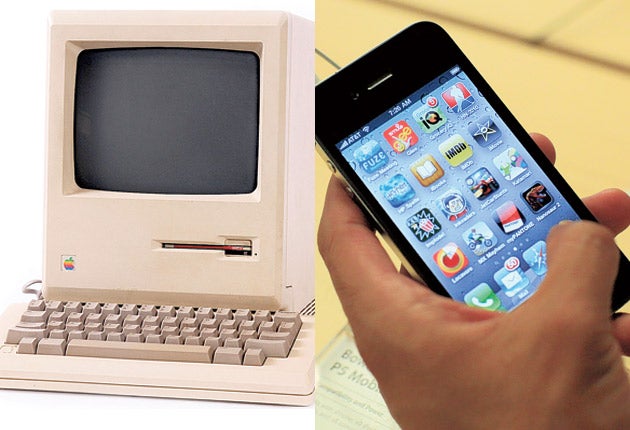

In the 1980s, a firm called Apple Computer produced a landmark device called the Macintosh. It was, by the standards of the time, a beautiful object, using a revolutionary point-and-click interface that had gadget fiends drooling.

Apple's strategy after that was simple: not to dilute the Macintosh brand by allowing other computer manufacturers to run its operating system, and not to sully the Mac itself by letting it run other operating systems. It was a nice idea, one that appealed to computer purists – and, thanks mainly to the advent of desktop publishing, gave Apple a small but well-established niche in the computer market.

But Microsoft, its main competitor, unleashed their operating system – Windows – with a carefree disregard for notions of computing purity. They let it run on any machine, figuring that the more people who used Windows, the better it would be for Microsoft.

They were right. Already dominant, the PC became almost ubiquitous, and for a while in the 1990s Apple looked like a spent force. Then, towards the end of the decade and with Steve Jobs back as CEO, Apple's fortunes changed – but its "locked-down" strategy certainly didn't.

Today, while the iPhone and its operating system, iOS, are hailed as masterpieces of design that have influenced almost every other modern mobile phone, is it possible that the success of a competing platform – Google's Android – could see Apple regretting its stance once again, some 20 years on?

The fun and functionality of modern phones are down to the apps – the mini applications that allow us to check train times, scan the night sky or time the boiling of an egg. The enthusiasm with which we download, install and play with these apps on our phones has seen developers coding like crazy with the aim of creating the next big sensation, and of course making some money into the bargain.

Until recently, attention was almost entirely focused on the iPhone; it's the iPhone that grabs headlines, it's iPhone apps that get blogged about, and it's iPhone users who are more likely to dip into their pockets. But Apple's controlling nature, while guaranteeing gadgets that have hardware and software working in perfect harmony, never sat well with the developer community.

An app can only end up on someone's iPhone if it has been approved by Apple, and a series of well-publicised rejections – many for seemingly spurious reasons – has had developers moaning about abandoning the platform altogether.

Thus far, they haven't deserted in droves – first because Android, the emerging alternative, has had far fewer users than the iPhone, and secondly because they're far more likely to make money out of Apple. At the moment, developers can only charge for Android apps in 13 countries worldwide, and even in countries where you can charge, most apps (57 per cent) are offered free, as opposed to 27 per cent of iPhone apps.

Most revenue to Google developers comes from advertising – which might explain why, up to now, Apple has paid out 50 times more cash to developers than Google has. This year we'll spend around $4.4bn (£2.9bn) on apps, of which 77 per cent will be collected by Apple, and just 9 per cent by Google; the benefits of developers continuing to work within Apple's restrictions still clearly outweigh the disadvantages.

But things are changing. Android is now being touted as the operating system of the future – not only for mobile phones, but also for tablet computers, televisions, car dashboards and anything else with a screen. Google are happy to hand Android out to manufacturers just as Microsoft allowed unfettered access to Windows in the 1980s and 1990s, and the effects of this are now beginning to show.

It's reported that 160,000 new Android devices were activated each day during June – up from 100,000 a day in May, a significant leap – while statistics from the advertising firm AdMob show that 26 per cent of their hits currently come from Android phones (up from 5 per cent at the same time last year).

In short, Android usage is rocketing – and it's not going unnoticed by the developers, on whom both Apple and Google rely so heavily for added value; well over half of developers believe that Android has the best long-term outlook, and one recent survey shows that, for the first time, there are now more Android developers than iPhone developers.

It's the global picture that Google and these ambitious developers have their eye on. While all the fuss in the affluent West is over iPhone and Android devices, low-cost phones running Nokia's tired-looking Symbian OS easily outsell both of them put together, thanks to colossal markets such as India and China, where the expensive iPhone has been unable to get a foothold. But it's those markets that Android will be aiming to break into in the next few months, as manufacturers in the Far East adopt the operating system to give their customers the best chance of having an iPhone-like experience on a budget.

By the end of next year, there's a good chance that Android devices will have displaced the iPhone in terms of sales – and an even better chance that developers will have jumped ship, attracted by moves Google are making to allow them to sell subscriptions and virtual goods from within apps, as well as selling the apps themselves.

Are Apple and its loyal supporters concerned about this, and with the grim reminders of Microsoft's triumph in desktop computing? Inevitably, they're keen to emphasise the quality of their design. You're guaranteed a more consistent experience with Apple products, they'll say, because Apple maintain overall control. They'll point out that Android devices could be made by any number of manufacturers using components of unknown origin. They'll quietly note that the Android Market – Google's version of the App Store – is littered with substandard apps, many of which break copyright law, because of a lack of policing – policing that developers continue to criticise Apple for implementing in their own store.

But the history of the Macintosh and the PC has shown that the vast majority of people aren't that bothered about badges, or exceptional quality. They just want something that works pretty well, and that doesn't break the bank. Apple's hope will be that, with tens of millions more customers this decade than they had in the mid-1980s, they'll have done enough to remain an exclusive producer of quality gadgets – the BMW of the technology world, if you like. But Google, big enough, powerful enough and relaxed enough to give away their Android operating system for nothing, are poised to move into pole position.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks