BBC micro:bit: Can a pocket-sized computer 'inspire digital creativity' in Britain's children?

The 4cm by 5cm device will be given free to all 11- and 12-year-olds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It promises to revive fond memories for a generation raised on the BBC Micro. Now the BBC has shrugged off calls to rein in its “imperial ambitions” by unveiling the BBC micro:bit, a successor to the popular 1980s home computer, which will be given free to every 11 and 12 year-old child in Britain.

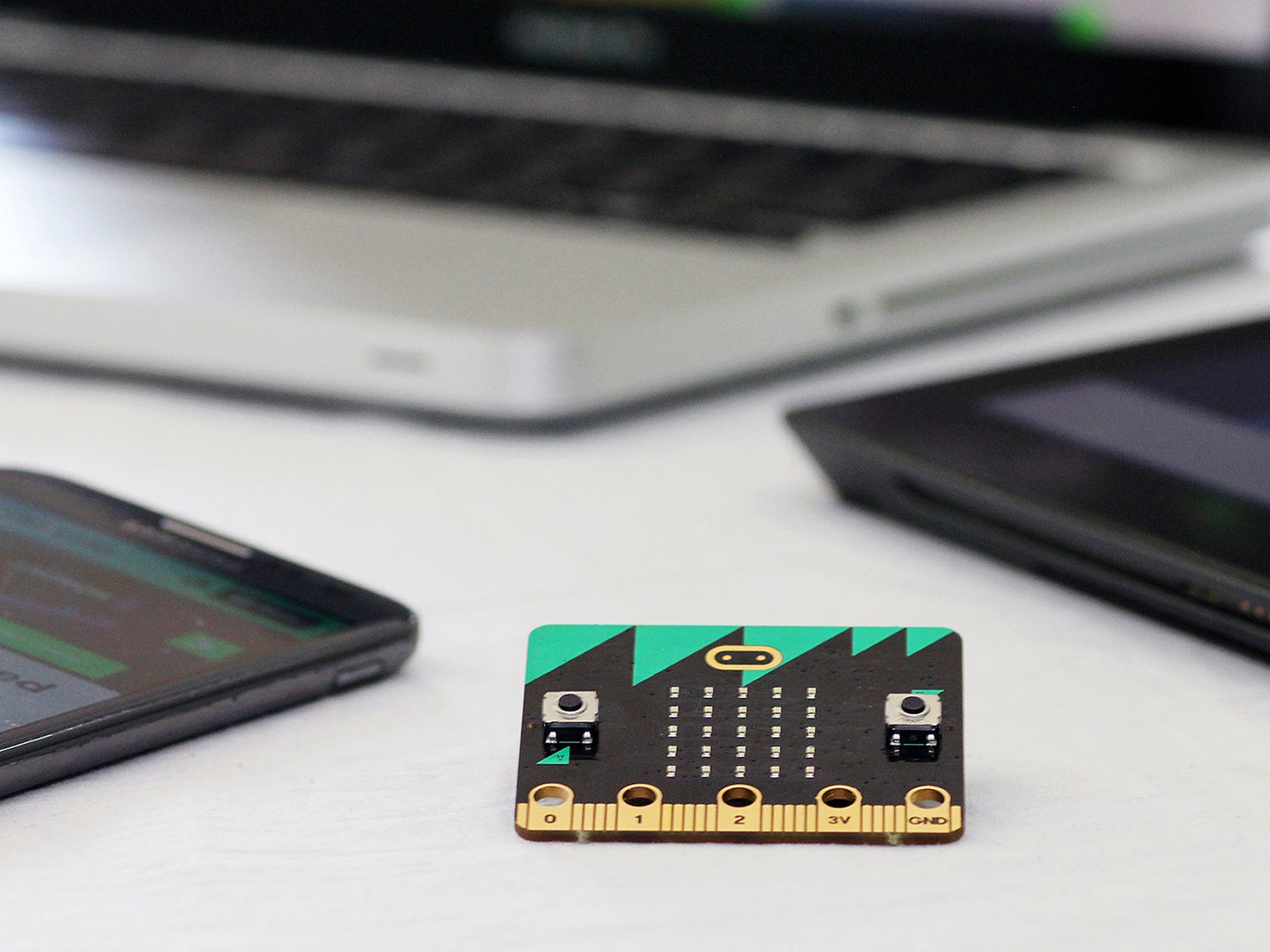

A pocket-sized computer, designed to help children get to grips with coding and “inspire digital creativity”, one million micro:bits will be rolled out across the UK from October, ensuring one for every year seven pupil.

Children will be allowed to take home and own the devices, which includes a Bluetooth antenna, USB plug and a processor, linked to a printed circuit board with a flashing LED display.

The BBC’s most ambitious education initiative since the launch of the BBC Micro, which introduced a generation of children to home computing, the micro:bit allows users to create games and send instructions to other digital devices.

Tony Hall, BBC Director-General, said the device would “channel the spirit of the Micro for the digital age” and by inspiring children to develop simple coding programs, help solve a “critical and growing skills gap” caused by a lack of computer science graduates in Britain.

The BBC, which has just accepted the £650m annual cost of providing free licence fees to over-75s, would not say how much it has invested in the 4cm by 5cm micro:bit, which has been developed with 28 partners including Microsoft, Samsung and the Wellcome Trust.

That information was “commercially confidential”, the BBC said. However the corporation said the micro:bit was intended to complement not rival commercially available lightweight computers already used for learning programming skills such as the Raspberry Pi and Arduino.

Schools may have to pay for the micro:bit, which is manufactured in China, after the initial rollout ends next year. The BBC said it had set up a not-for-profit company, alongside its partners, which will license the micro:bit, in order to get more devices to children. The computers will also be sold overseas but the BBC said it would gain no financial benefit from the commercialisation of its intellectual property.

The BBC had hoped that each micro:bit, which is 18 times faster and 17 times lighter than the Micro, would cost just £2 to manufacture. But a wearable prototype which included a slot for a thin battery had to be changed because it proved too expensive.

A power pack, fitted with AA batteries, is needed to use the device as a standalone product. The BBC said it had yet to agree with schools whether batteries would be included when the devices are sent out.

Its developers hope the micro:bit will inspire more girls to learn coding and challenge children, used to downloading apps with one click, to learn what lies behind the intuitive technology of their smartphones and tablets. Teachers will be given tutorials in the device before handing it over to pupils.

Sinead Rocks, Head of BBC Learning, which developed the device over three years, said: “We happily give children paint brushes when they’re young, with no experience - it should be exactly the same with technology. The BBC micro:bit is all about young people learning to express themselves digitally, and it’s their device to own. It’s able to connect to everything from mobile phones to plant pots and Raspberry Pis. This could be for the internet-of-things what the BBC Micro was to the British gaming industry.”

The micro:bit contains a built-in magnetometer sensor which could be used to help create a metal detector, an accelerometer to make a hi-tech spirit level, a Bluetooth chip to control a DVD player and buttons to create a video games controller. Ms Rocks said it would be a “springboard” to the Raspberry Pi, which is aimed at older users.

Derrick McCourt, general manager, public sector for Microsoft UK, said: “The exciting thing for us is that the next Bill Gates could come out of year seven. The micro:bit isn’t just for techies and nerds, we need more women in the technology workforce. We hope to create a new generation who think coding is exciting.”

He added: “We have a lot of catching up to do – Poland is producing four times as many computer science graduates as the UK.”

User guide

As a BBC Micro user at the dawn of the 80s I immediately sensed that home computer’s possibilities – by junking the boring BASIC computer programming tools and playing alien invasion game Arcadians.

Now the micro:bit is here to show me that coding was fun all along. The slimline circuit board with its flashing LED display looks like a malfunctioning SIM card.

The device is connected to a “simulator”, a BBC website where codes can be written and ideas tested.

With the help of a Microsoft assistant (presumably every school will have one), a sea of “function main () – show string”-type WTF commands on a .hex drive are “flashed” to the micro:bit. Its LED display lights up with a dice display. Shake the micro:bit and a new number appears on the surface. Neat.

Before long we are getting familiar with programming languages such as Python and Blockly and using micro:bit to turn up the volume on a specially-modified digital guitar. Stick it in a DIY Thirsty Plant Kit and micro:bit will show you when the soil needs watering.

Digital native kids will have great fun programming the micro:bit as a sensor to detect when siblings are creeping into their room. The only question is whether teachers have the skills to keep up when the devices flood classrooms this Autumn.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments